It’s largely been forgotten but Mussolini, the vain Italian fascist, was often seen in a relatively good light during the 1920s and 1930s. Playwrights, politicians, famous men of peace and Hollywood stars were amongst many who became simpering fans. His ‘reign’ lasted from 1922, when he became Prime Minister until he was executed in April 1945 by an Italian partisan in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra in northern Italy. After he was summarily shot his body, along with other fascists, was subsequently hoisted up on the metal frame of a half-built Standard Oil service station, and hung upside down on meat hooks in the Piazzale Loreto, a suburban square near the main railway station. The location was not an accident. Eight months previously fifteen partisans had been shot in the square and their bodies had then been left on public display.

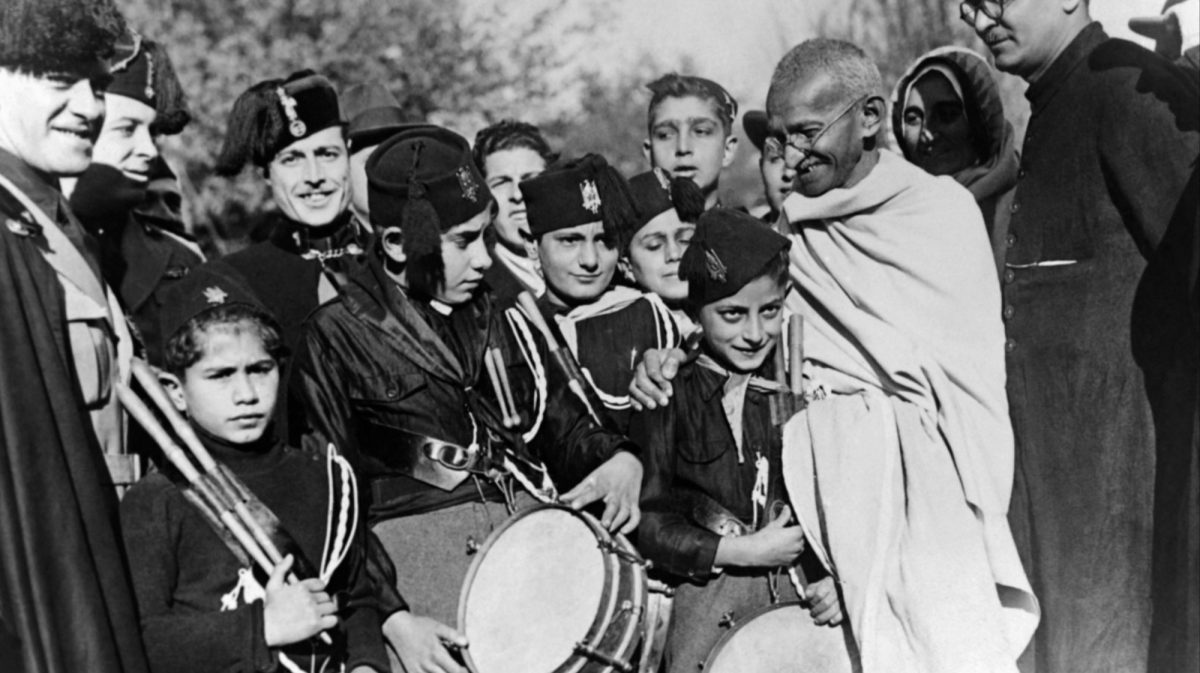

In late 1931 while he was touring Europe, Gandhi accepted an invitation to visit Mussolini in Rome where he even reviewed a black-shirted Fascist youth honour guard during his stay. Regarding his visit with Il Duce, Gandhi wrote in a letter to a friend: “Many of his reforms attract me. He seems to have done much for the peasant class. I admit an iron hand is there. But as violence is the basis of Western society, Mussolini’s reforms deserve an impartial study…My own fundamental objection is that these reforms are compulsory. But it is the same in all democratic institutions.” Gandhi would also hail Mussolini “one of the great statesmen of our time.”

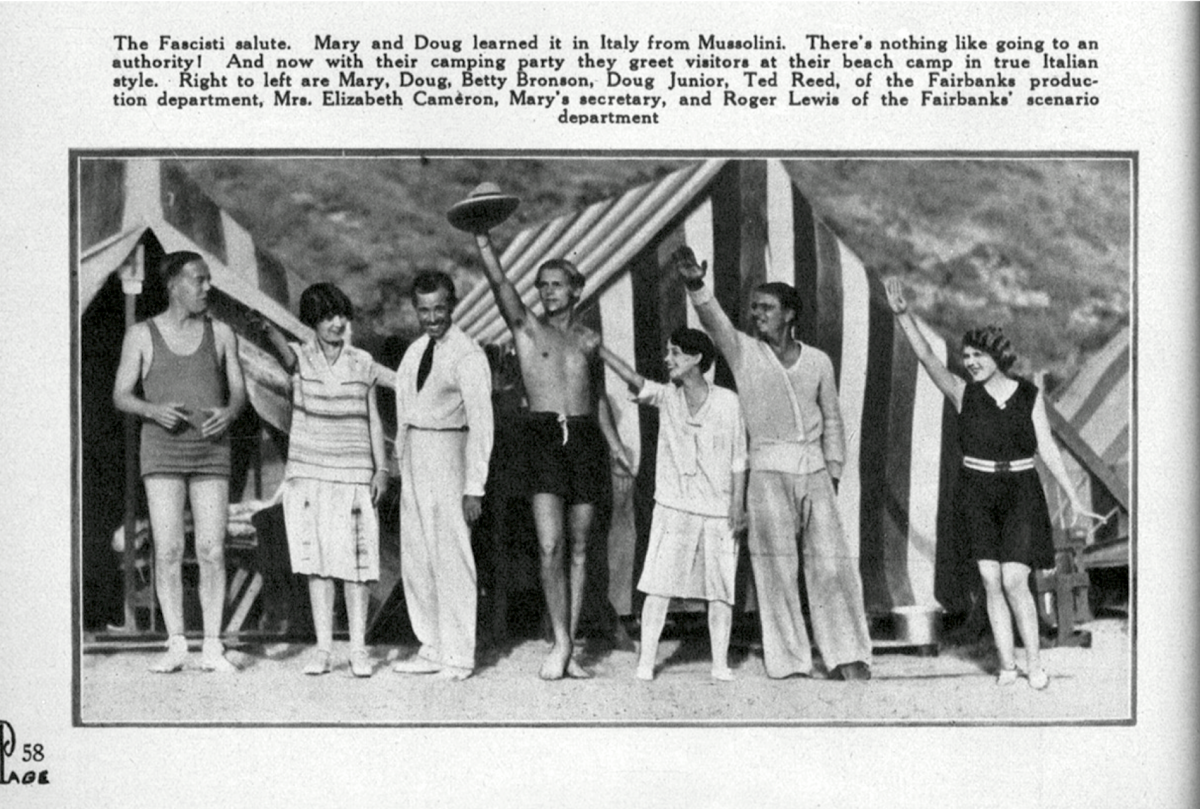

George Bernard Shaw once declared of the Italian dictator, “Socialists should be delighted to find at last a socialist who speaks and thinks as responsible rulers do.” While Winston Churchill once called Mussolini “the greatest living legislator” and wrote to his wife in 1926, saying “No doubt he is one of the most wonderful men of our time.” Clementine responded a few days later quoting a friend of theirs, “It is better to read about a world figure, than to live under his rule.” In the spring of the same year Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks visited Italy including Rome where they met Mussolini and Pickford greeted the press with what a local newspaper described as a “saluto fascista.” Giorgio Bertellini reports in his book The Divo and the Duce that at the same time Fairbanks proudly placed a fascist pin in his buttonhole, promising to carry it in and out of Italy, as long as he was in Europe to his wife’s approving nod.

British statesman Winston Churchill (1874 – 1965) and his wife Clementine (1885 – 1977) arrive at Waterloo Station in London, after a visit to the United States, November 1929. (Photo by Gaiger/Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

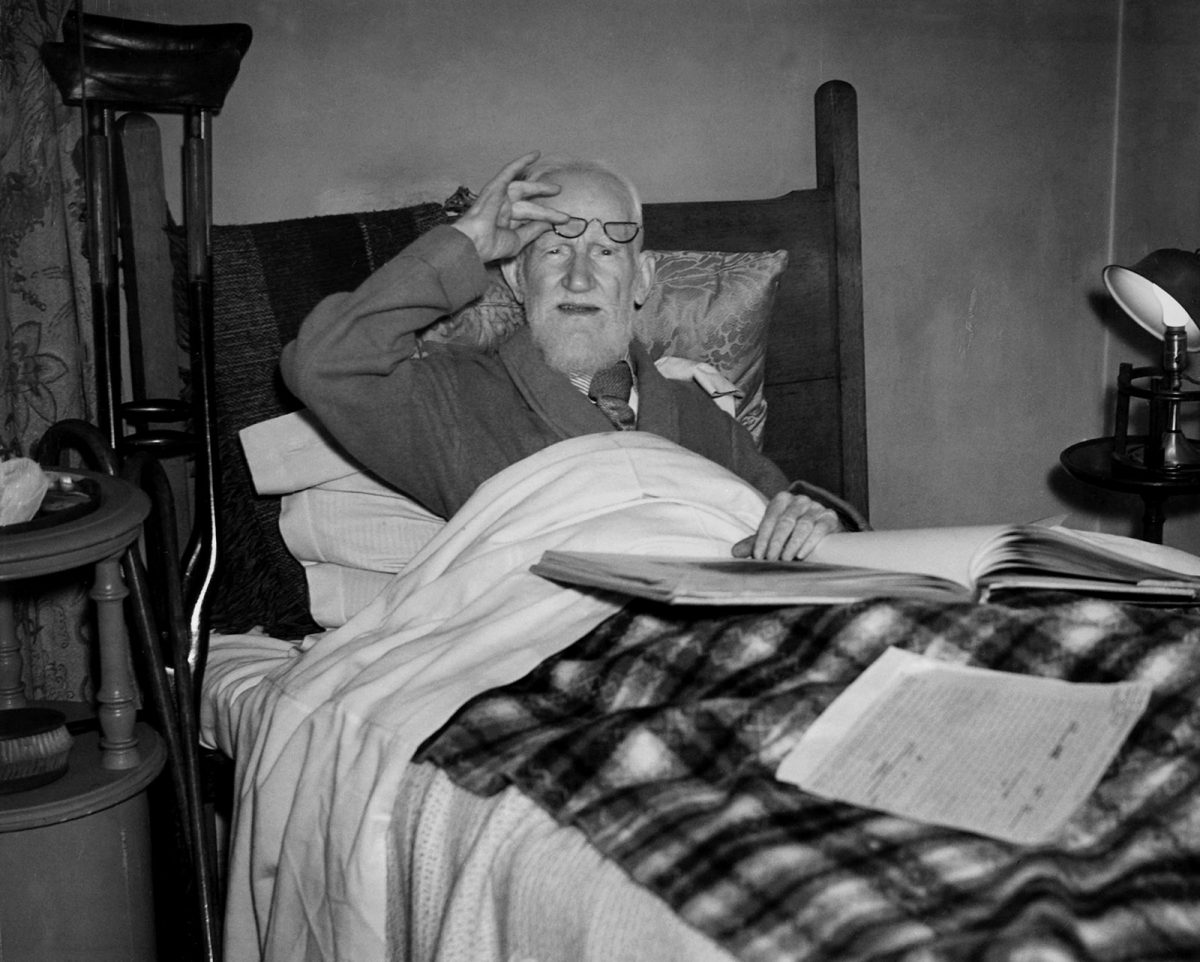

George Bernard Shaw, Whitehall Court, London, October 1946

Benito Mussolini and US Secretary of State Henry Stimson, Rome, July 1931

Mussolini actually visited London, albeit for a rather brief stay, in December 1922 for a conference on German Reparations. He arrived at Victoria Station on 9 December 1922, apparently on time, and no one quite knew what to make of him. One newspaper had to explain what his black-shirted supporters were doing when they ‘held high their right arms, with the hands spread slantingly forward’. The Manchester Guardian in an article published two months before the trip wrote: “The subtle Italian mind adores a man of action, a man of elemental force. Mussolini, “the Thunderer,”…has swept most of young Italy off their feet, and for the time being holds them in the hollow of his hand.” While the Times was also impressed, “Signor Mussolini has an air of authority and a dominating personality.”

When Mussolini got to Victoria Station on a boat train he was met by about fifty black-shirted supporters. The Guardian, like many newspapers of the time, found the uniformed fascists faintly amusing and their correspondent thought that all the energetic marching about was to do with the cold and worried that the thin “black shirt (with it a black tie, some war medals, and a black cloth cap shaped like a fez with a tussle and cord) looked poor comfort for eleven o’clock on a slightly foggy December night.” He then described them raising a “shout very like “hooray” before all singing the Italian Fascist Marching song ‘Giovinezza’. This was all repeated half an hour later outside Claridge’s Hotel where Mussolini and his entourage were staying. In fact during his entire stay organised groups of Blackshirts greeted him and sang the fascist marching song wherever he went. At Claridge’s there was a loud and unseemly row when the Italian delegation accused their French counterparts of being allocated better rooms.

Italians at the Cenotaph, Whitehall, London, give the Fascist salute after doing so. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

November 1922: Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945). (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The 39 year old Italian leader wore spats and a Butterfly collar with a top hat and badly pressed striped trousers, which led the aristocratic British Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, to remark, “He is really quite absurd.” While most people were also surprised by his small stature (Mussolini was only five foot six inches). The next day Mussolini and his party were received at Buckingham Palace by the King, where it didn’t go down well that Mussolini insisted on wearing his Fascist Party badge to the palace and then at 2.45 the Italian Premier and his colleagues drove to the Cenotaph in Whitehall where Signor Mussolini laid a wreath of remembrance at the foot of the monument. He was received by the Earl of Derby (Secretary for War) and the Earl of Cavan (Chief of the Imperial General Staff). He then visited the Italian Fascist HQ at 25 Noel Street. At one point Mussolini missed a press conference because he was sleeping with a prostitute back at the hotel. During his stay he complained incessantly about the fog which he insisted penetrated his clothes, his bedroom and even his suitcases. When he returned to Italy he swore that he would never return to England, and never did.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.