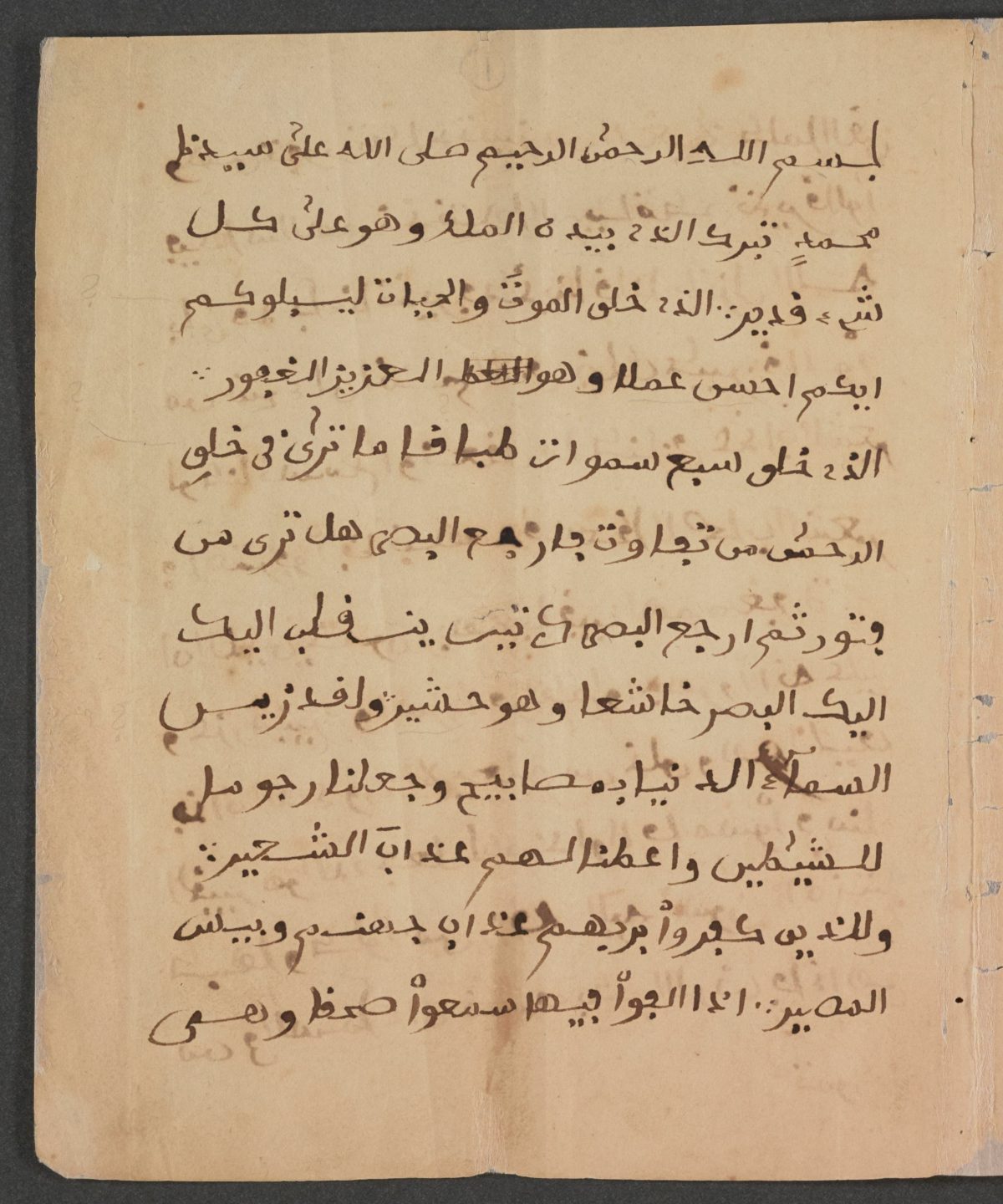

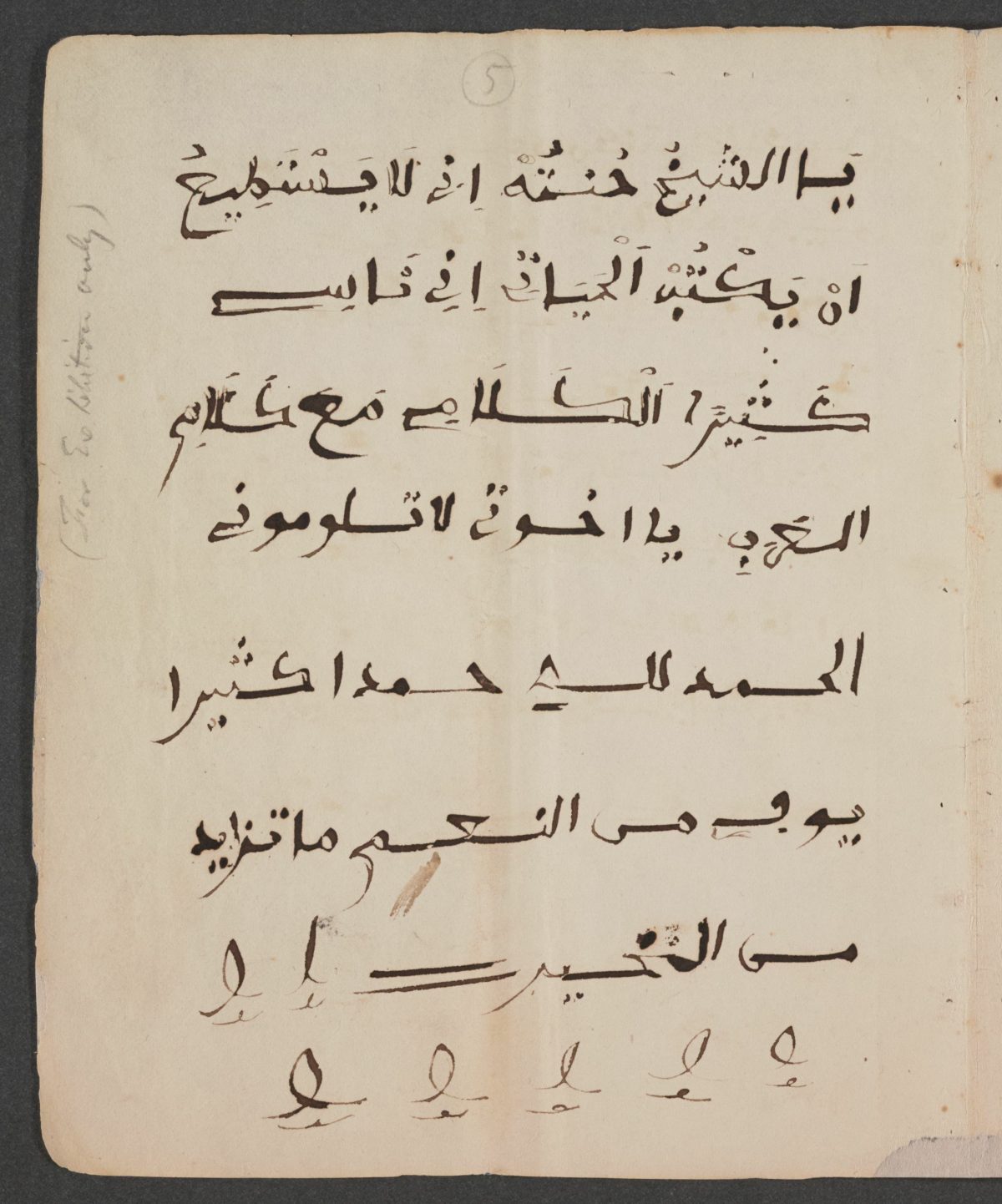

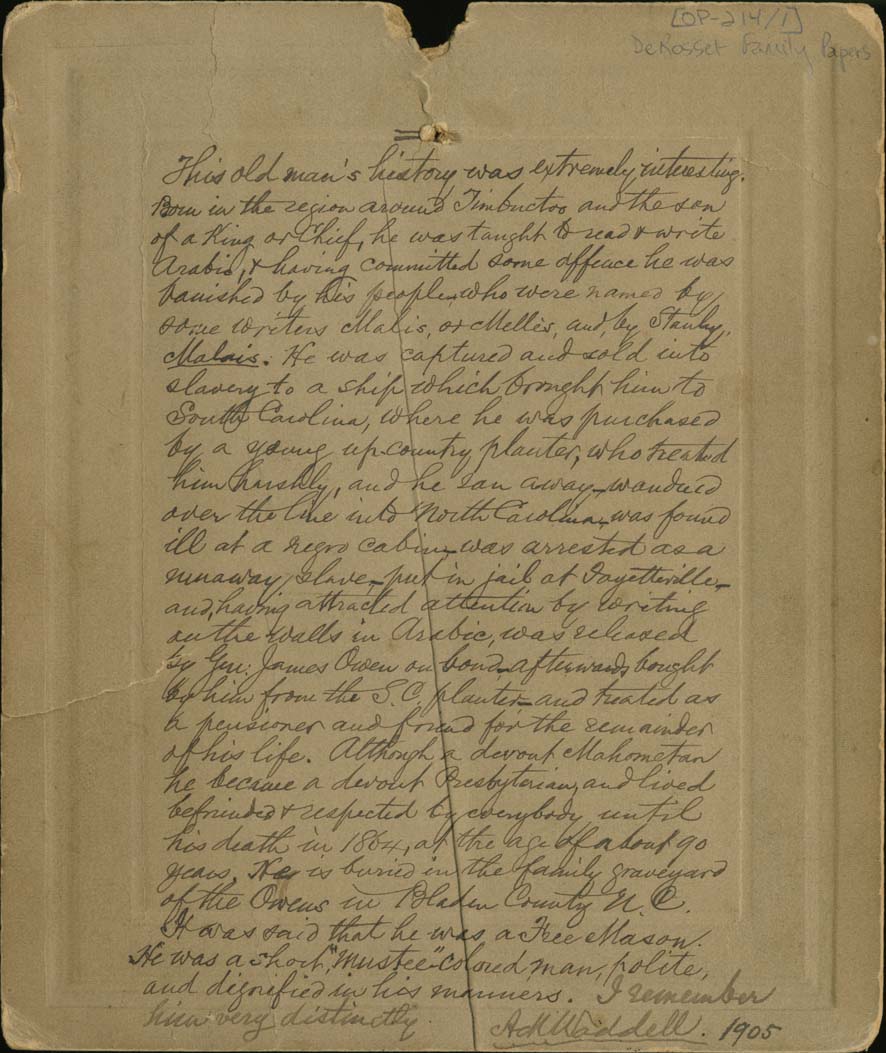

The Life of Omar ibn Said tells the story of a “prince” stolen from West Africa in 1807 and transported to South Corolina to work as a slave. In 1831 Ibn Said (1770-1863 or 1864), a practising Muslim, wrote his autobiography in Arabic while still in captivity. It is the only known extant autobiography of a slave written in Arabic in America. The work of 15 handwritten pages was unedited by the writer’s owner, giving it an air of authenticity. And it proved to doubters that Africa was steeped in literary culture, and Abrahamic and monotheistic faiths long before the civilising presence of the white man educated them in the missionary styles and offered one-way trips to the pristine ‘New World’. The simple, monocular view of Africa and Africans as something other than entirely human, noble savages reared on Western paternalism that masked awkward thoughts, is blown away.

Ibn Said tells us he was first sold to a “small and evil man who did not fear God”. Ibn Said escaped, working from plantation to plantation until his capture in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Jailed for 16 days, Ibn Said was spotted writing in Arabic on the cells wall. In the article “Prince Moro” in The Christian Advocate (Philadelphia) 3 July 1825, it’s noted: “As no one claimed him, and he appeared of no value, the jail was thrown open, that he might run away; but he had no disposition to make his escape.” Sold for his “jail dues”, Omar Ibn Said became the property of General John Owen, the brother of the governor of North Carolina, where he worked until his death in 1863. He converted to Christianity.

“I was afraid to remain with a man so depraved and who committed so many crimes and I ran away. After a month our Lord God brought me forward to the hand of a good man, who fears God, and loves to do good, and whose name is Jim Owen and whose brother is called Col. John Owen. These are two excellent men. I am residing in Bladen County. I continue in the hand of Jim Owen who never beats me, nor scolds me. I neither go hungry nor naked, and I have no hard work to do. I am not able to do hard work for I am a small man and feeble. During the last twenty years I have known no want in the hand of Jim Owen.”

– Omar Ibn Said

Before his capture in Africa, Ibn Said embarked on a pilgrimage to Mecca, prayed five times a day, visited the mosque, fought a jihad and gave alms to the poor. He writes: “I used to give alms … every year in gold, silver, harvest, cattle, sheep, goats, rice, wheat and barley – all I used to give in alms.”

We know more. He was a member of theFula ethnic group born in Fut Tur, or Futa Toro, located between the two rivers of Senegal and the Gambia. He was well educated. “I continued seeking knowledge for 25 years,” he notes. His father, who died when Omar was five and is said to have been a king, had six sons and five daughters; his mother had three sons and one daughter.

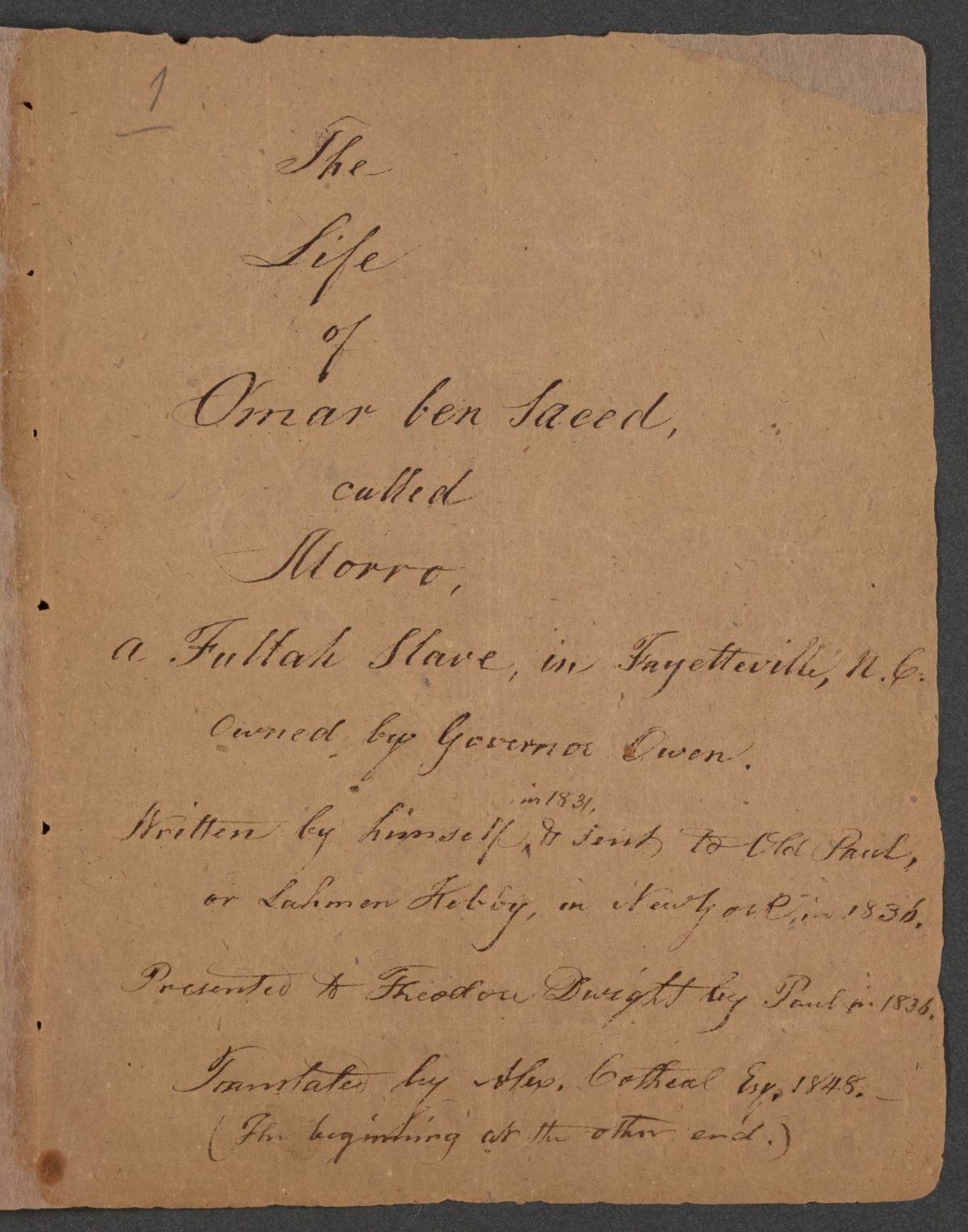

Ibn Said wrote his autobiography in response to a request by someone he referred to as “Sheikh Hunter” and apparently also at the request of Theodore Dwight (1796–1866), a founder of the American Ethnological Society and a member of the New York Colonization Society, either directly or through the slave owner. It is thanks to Dwight that much of this collection of documents still exists…

Dwight, as well as other prominent colonizationists, wanted Ibn Said to write his autobiography, and wanted it to be translated, to undermine claims justifying slavery in the United States. The autobiography was meant to bolster an argument linking literacy and monotheism to manumission, or the freeing of slaves. Dwight was also interested in Islam and in educating Americans about Africa and the people they were capturing and enslaving.

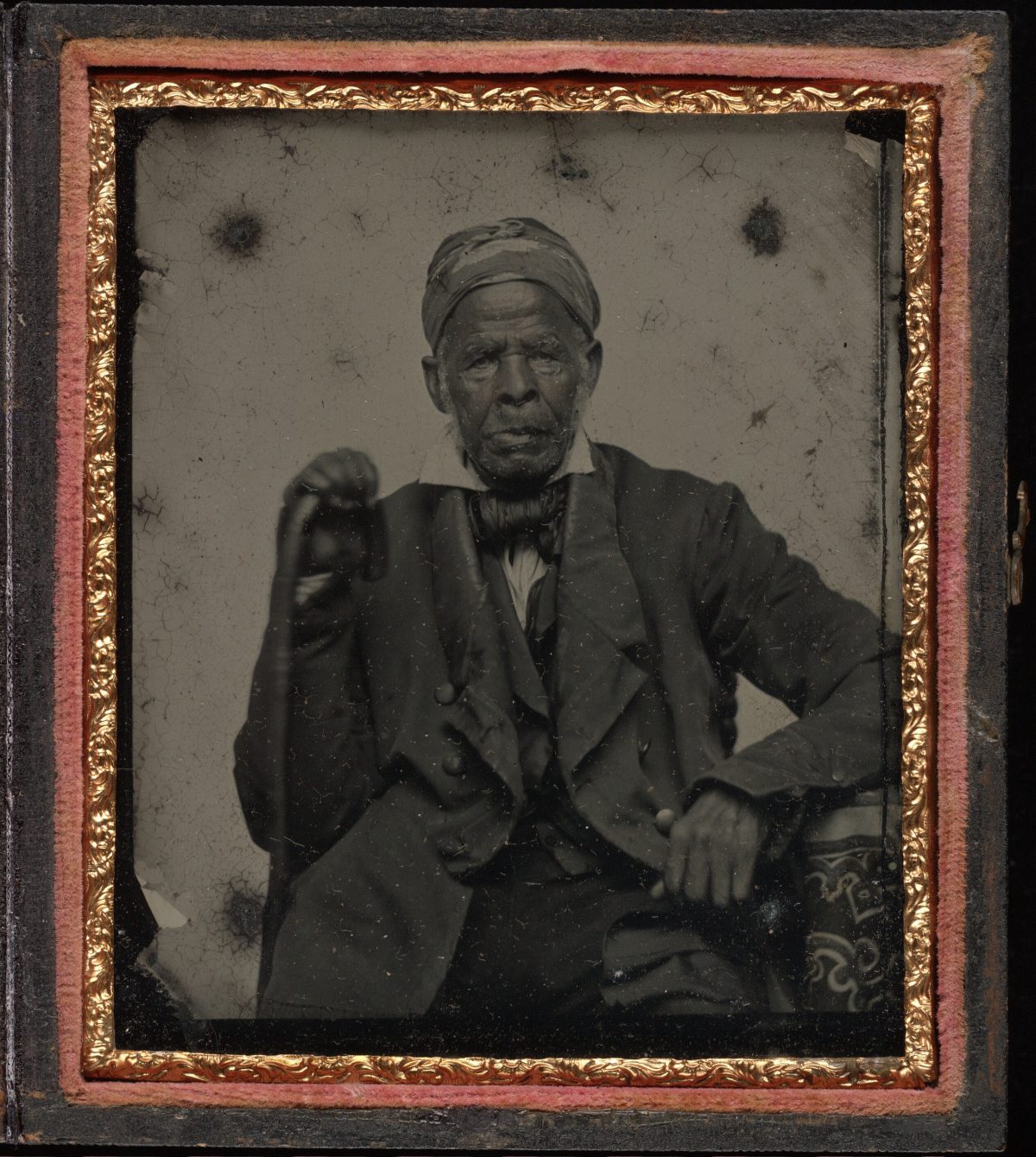

![[Portrait of Omar ibn Said] Click here for a smaller image "Uncle Moro" (Omeroh), the African (or Arab) Prince whom Genl. Owen bought, and who lived in Wilmington N.C. for many years, and died in Bladen Co. in 1864, aged about 90 years. see other side](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/said_150.jpg)

Portrait of Omar ibn Said

“Uncle Moro” (Omeroh), the African (or Arab) Prince whom Genl. Owen bought, and who lived in Wilmington N.C. for many years, and died in Bladen Co. in 1864, aged about 90 years. see other side

Verso of Portrait of Omar ibn Said

Much of what we know is found in account of Omar ibn Said from journals of the period.

From The Wilmington Chronicle 27 January 1847.

In the Providence, R. I. Journal, there have been published within the past year a good many well written letters descriptive of matters and things in North Carolina; some of them exceedingly interesting. In one of those which appeared lately there is an account (copied below) of an individual well known in this community, and who, although a slave, is held in high respect and esteem. We refer to Monroe, the servant of General Owen. Monroe is probably more than seventy-five years of age, instead of sixty, as the letter writer supposes. He belonged to the Foulah tribe in Africa, who inhabit the region about the sources of the Senegal river. The Foulahs, or Fallatas, are known as the descendants of the Arabian Mahomedans who migrated to Western Africa in the seventh century. They carried with them the literature of Arabia, as well as the religion of their great Prophet, and have ever retained both. The Foulahs stand in the scale of civilization at the head of all the African tribes.

Monroe was a teacher among his own people. He still writes the Arabic with considerable facility. A specimen of his writing in that language is now before us. He was thirty-six or thirty-seven years old when brought from Africa. He was landed at Charleston, remained in South Carolina four years, and has been thirty-seven years in this State, the greater portion of them in the family of General Owen.

EXTRACT FROM THE LETTER IN THE JOURNAL.

With this I send you a manuscript in Arabic. It does not set up any pretensions to antiquity, and hence it need not puzzle that portion of the literati who are eternally on the scent for ancient lore, and who can be satisfied with nothing unless of sufficient age to become the basis of an unending squabble of pens, in which these learned notables are ever certain to treat the few who take the trouble to scan their effusions, with a dish of “confusion worse confounded.” To gratify the tastes and fancies of these lovers of the antique, it is surprising how human ingenuity and perseverance have, of late, contrived to exhume ancient manuscripts, and to call up, from the musty repositories where they have slumbered for ages, specimens of the literary handiwork of by-gone times:—Albeit, certain humane and obliging specimens of the knowing ones, sometimes have the generosity to manufacture ancient matters and things, which pass equally well with the real Simon Pures, and make just as good a quarrel. The scrap I send you, however, though modern, is genuine. It is not from Mecca, or Medina, or any other Arabian city; nor is there any dispute or doubt about its authorship. In short, it comes direct from the “Old North State,” and is the production of an old and superanuated [sic] slave. I leave it to you to judge, therefore, if it is not quite as remarkable to find an Arabic scholar under such a guise, as to find a scrap of antiquity deposited on the mouldering shelf of some ancient library, or amidst the ruins of an antique temple. But I will give you a short scrap of the history of the writer.

The name of the man from whom I obtained this manuscript for you, I believe is Monroe; and he would seem to be some sixty years of age. He is an Arab by birth, of royal blood, and was captured during a war between his own and a neighboring tribe, conveyed to the coast, and sold as a slave. Whether he was brought directly to North Carolina, or not, I am unable to say; but I have known him at Wilmington, if my memory serves me, for twenty years. He has been extremely fortunate as respects a master. He fell into the hands of Gen. Owen, of Wilmington, who, naturally of a generous and humane disposition, has treated him with extreme lenity, and indeed more like a relative than a servant. Indeed the General, many years since, proffered him his freedom, and offered to send him back to his native land. But Monroe declined the offer, saying that his friends were probably either destroyed or dispersed, and that his condition was much better where he was, than it could be in his own country. This venerable man is well built, of a middling height, with an open and cheerful countenance, correct in his deportment, and gentlemanly and conciliating in his manners. He is respected by those who know him, and is a worthy member of the Presbyterian church. You will perceive that the penmanship is bold and handsome. The manuscript, the translator says, contains the Lord’s Prayer, and the Twenty-Second Psalm. Is it not a little remarkable, that a man who has not probably heard his vernacular tongue spoken, nor seen it written, for thirty years, except by himself, should now, at the age of three score, and a slave, be able to write it fluently and correctly?

Ambrotype of Omar Ibn Said

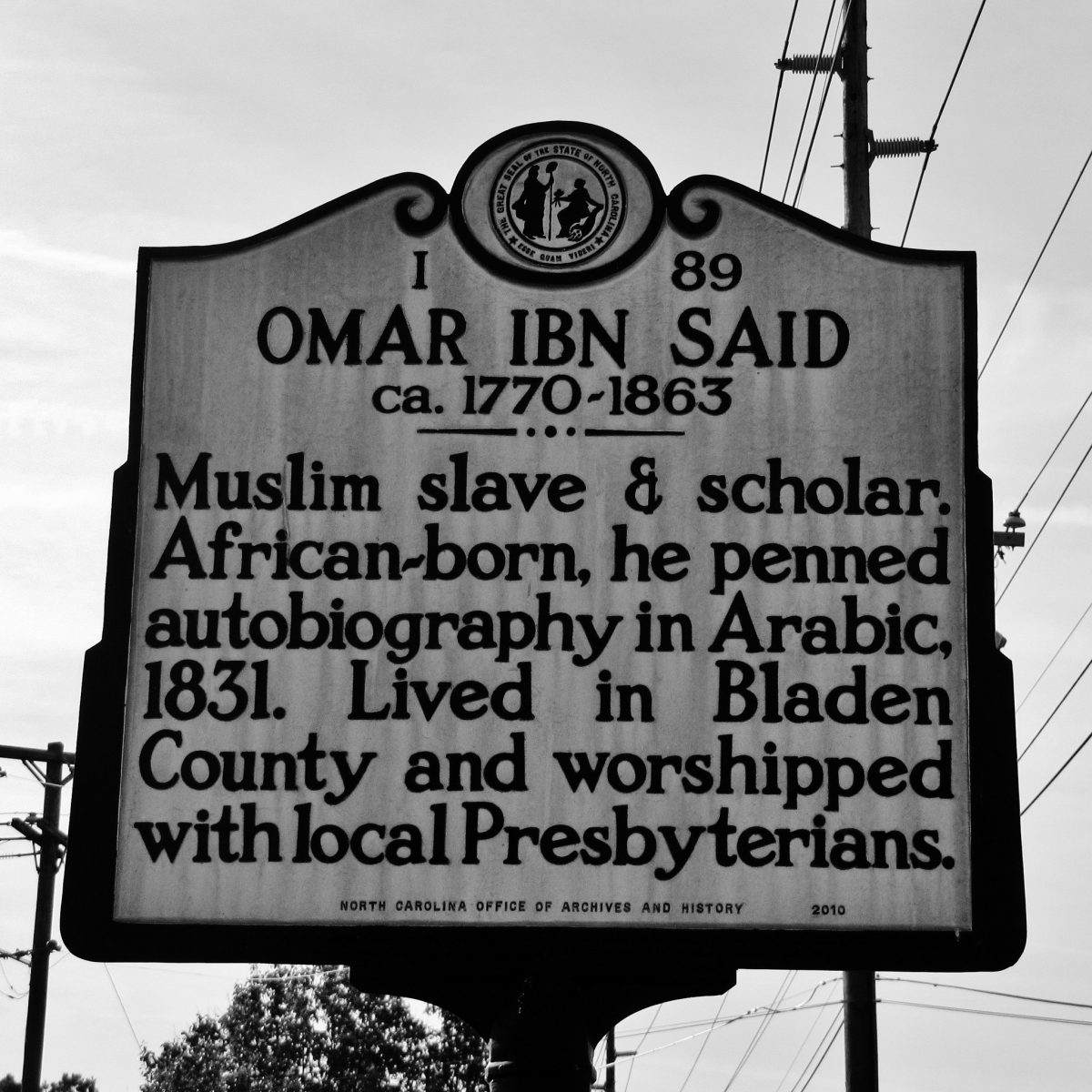

The historic marker for Omar Ibn Said is on Murchison Road, North Carolina Highway 210 in Fayetteville, North Carolina in Cumberland County. Via

North Carolina University Magazine September, 1854: the story was headlined “UNCLE MOREAU“.

“Uncle Moreau” is now well stricken in years, being, according to his own account, eighty-four years of age. He was born in eastern Africa, upon the banks of the Senegal River. His name, originality [sic] was Umeroh. His family belonged to the tribe of Foutahs, whose chief city was Foutah. The story that he was by birth a prince of his tribe, is unfounded. His father seems to have been a man of considerable wealth, owning as many as seventy slaves, and living upon the proceeds of their labour. The tribes living in eastern Africa are engaged almost incessantly in predatory warfare, and in one of these wars the father of Moreau was killed. This occurred when he was about five years old, and the whole family were immediately taken by an uncle to the town of Foutah. This uncle appears to have been the chief minister of the King or Ruler of Foutah. Here Moreau was educated, that is, he was taught to read the Koran (his tribe being Mohamedans) to recite certain forms of prayer, and the knowledge of the simpler forms of Arithmetic. So apt was he to learn, that he was soon promoted to a mastership, and for ten years taught the youth of his tribe all that they were wont to be taught, which was for the most part, lessons from the Koran. Those barbarians did not think, like the more Enlightened States of excluding their sacred books from their schools.

After teaching for many years, Moreau resolved to abandon this pursuit and become a trader, the chief articles of trade being salt, cotton cloths, &c. While engaged in trade, some event occurred, which he is very reluctant to refer to, but which resulted in his being sold into slavery. He was brought down the coast, shipped for America, in company with only two who could speak the same language, and was landed at Charleston in 1807, just a year previous to the final abolition of the slave trade. He was soon sold to a citizen of Charleston, who treated him with great kindness, but who, unfortunately for Moreau, died in a short time. He was then sold to one who proved to be a harsh cruel master, exacting from him labour which he had not the strength to perform. From him Moreau found means to escape, and after wandering nearly over the State of South Carolina, was found near to Fayetteville in this State. Here he was taken up as a runaway, and placed in the jail. Knowing nothing of the language as yet, he could not tell who he was, or where he was from, but finding some coals in the ashes, he filled the walls of his room with piteous petitions to be released, all written in the Arabic language. The strange characters, so elegantly and correctly written by a runaway slave, soon attracted attention, and many of the citizens of the town visited the jail to see him.

Through the agency of Mr. Mumford, then Sheriff of Cumberland county, the case of Moreau was brought to the notice of Gen. Jas. Owen, of Bladen county, a gentleman well known throughout this commonwealth for his public services, and always known as a man of generous and humane impulses. He took Moreau out of jail, becoming security for his forthcoming if called for, and carried him with him to his plantation in Bladen county. For a long time his wishes were baffled by the meanness and the cupidity of a man who had bought the runaway at a small price from his former master, until at last he was able to obtain legal possession of him, greatly to the joy of Moreau. Since then, for more than forty years, he has been a trusted and indulged servant.

At the time of his purchase by Gen. Owen, Moreau was a staunch Mohamedan, and the first year at least kept the fast of Rhamadan, with great strictness. Through the kindness of some friends, an English translation of the Koran was procured for him, and read to him, often with portions of the Bible. Gradually he seemed to lose his interest in the Koran, and to show more interest in the sacred Scriptures, until finally he gave up his faith in Mohammed, and became a believer in Jesus Christ. He was baptized by Rev. Dr. Snodgrass, of the Presbyterian Church in Fayetteville, and received into the church. Since that time he has been transferred to the Presbyterian Church in Wilmington, of which he has long been a consistent and worthy member. There are few Sabbaths in the year in which he is absent from the house of God.

Uncle Moreau is an Arabic scholar, reading the language with great facility, and translating it with ease. His pronunciation of the Arabic is remarkably fine. An eminent Virginia scholar said, not long since, that he read it more beautifully than any one he ever heard, save a distinguished savant of the University of Halle. His translations are somewhat imperfect, as he never mastered the English language, but they are often very striking. We remember once hearing him read and translate the twenty-third psalm, and shall never forget the earnestness and fervour which shone in the old man’s countenance, as he read of the going down into the dark valley, and using his own broken English said, ‘Me, no fear, master’s with me there.” There were signs in his countenance and in his voice, that he knew not only the words, but felt the blessed power of the truth they contained.

Moreau has never expressed any wish to return to Africa. Indeed he has always manifested a great aversion to it when proposed, changing the subject as soon as possible. When Dr. Jonas King, now of Greece, returned to this country from the East, he was introduced in Fayetteville to Moreau. Gen. Owen observed an evident reluctance on the part of the old man to converse with Dr. King. After some time he ascertained that the only reason of his reluctance was his fear that one who talked so well in Arabic might have been sent by his own countryman to reclaim him, and carry him again over the sea. After his fears were removed he conversed with Dr. King with great readiness and delight.

He now regards his expatriation as a great Providential favour. “His coming to this country,” as he remarked to the writer, “was all for good.” Mohammedanism has been supplanted in his heart by the better faith in Christ Jesus, and in the midst of a christian family, where he is kindly watched over and in the midst of a church which honors him for his consistent piety.—He is gradually going down to that dark valley, in which, his own firm hope is, that he will be supported and led by the hand of the Great Master, and from which he will emerge into the brightness of the perfect day.

The Omar Ibn Said Collection at the Library of Congress. Via.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.