“Hot sex. They can’t do what we do and they hate us for it.” – Don Draper

The television show Mad Men

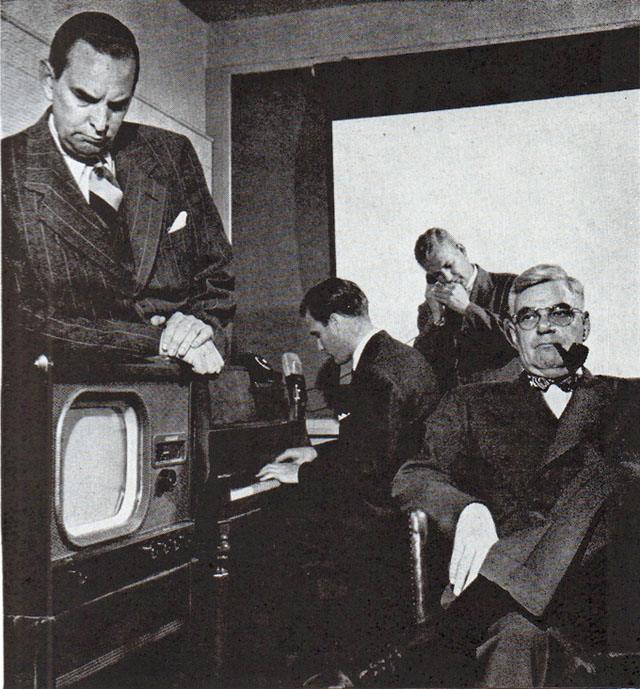

It’s no wonder Don wanted a part of this world. Madison Avenue ad men were the ultimate gentlemen’s club.

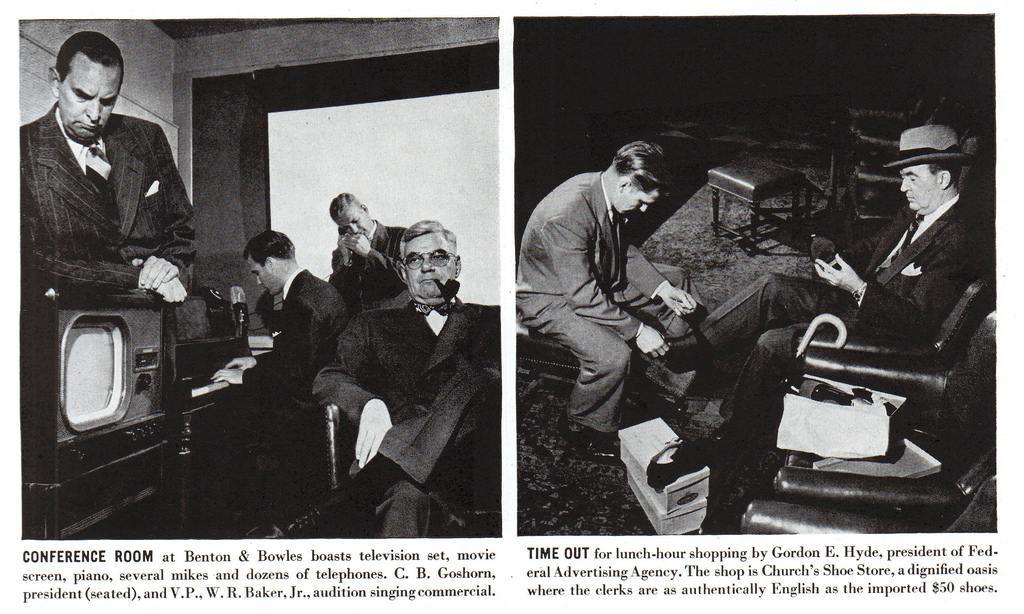

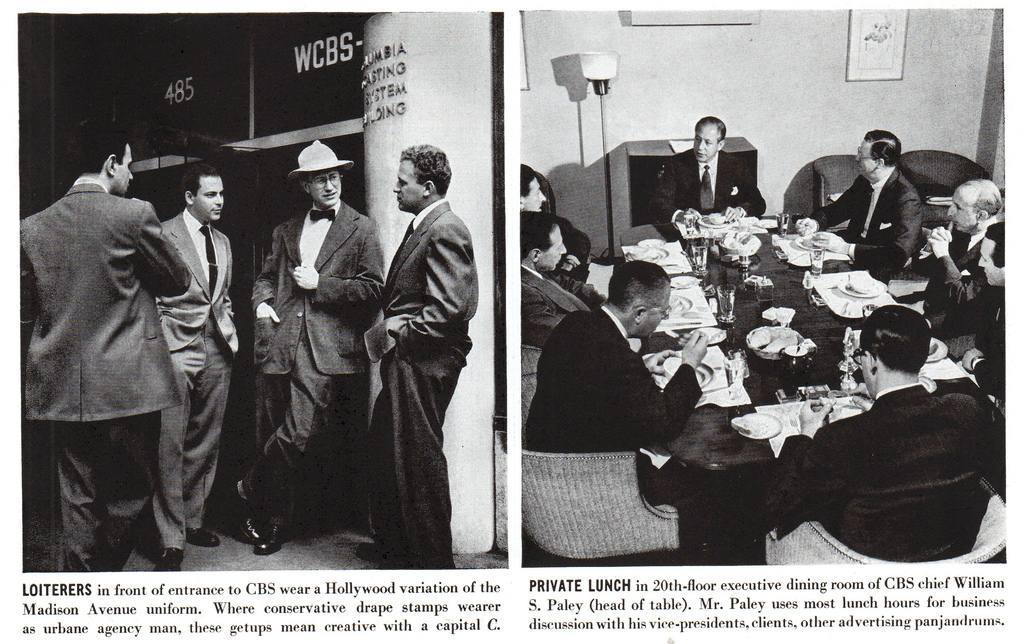

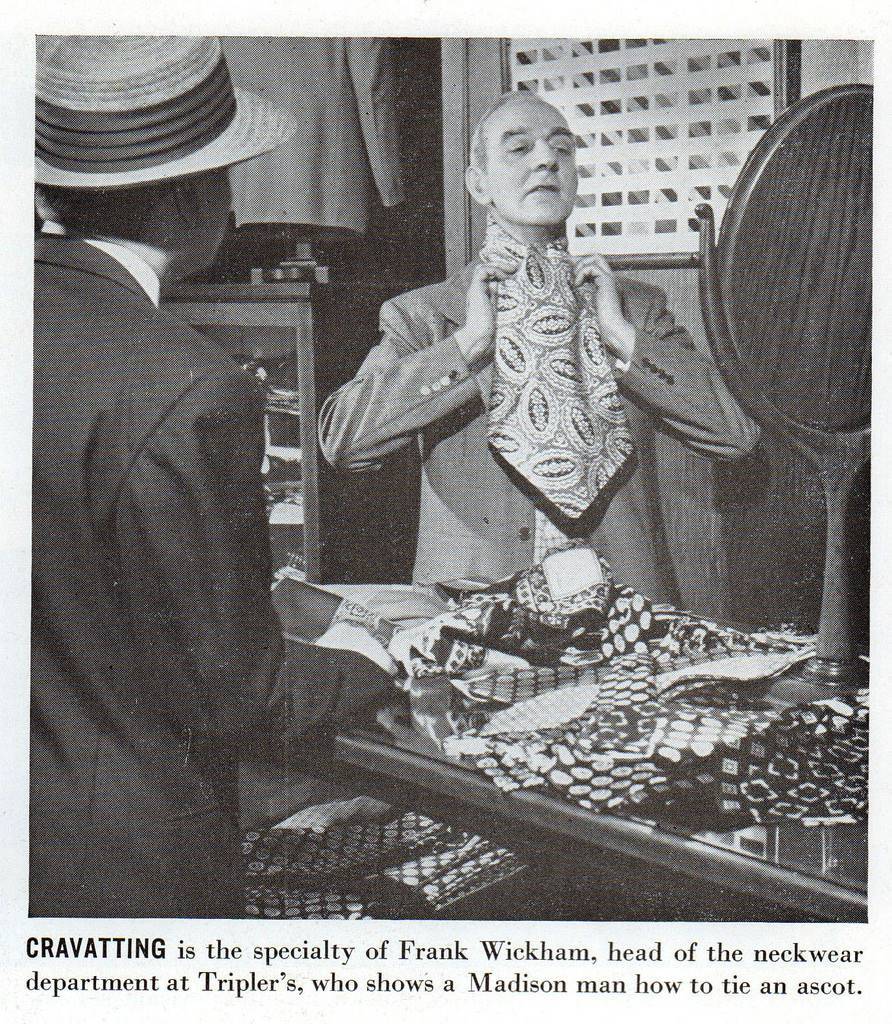

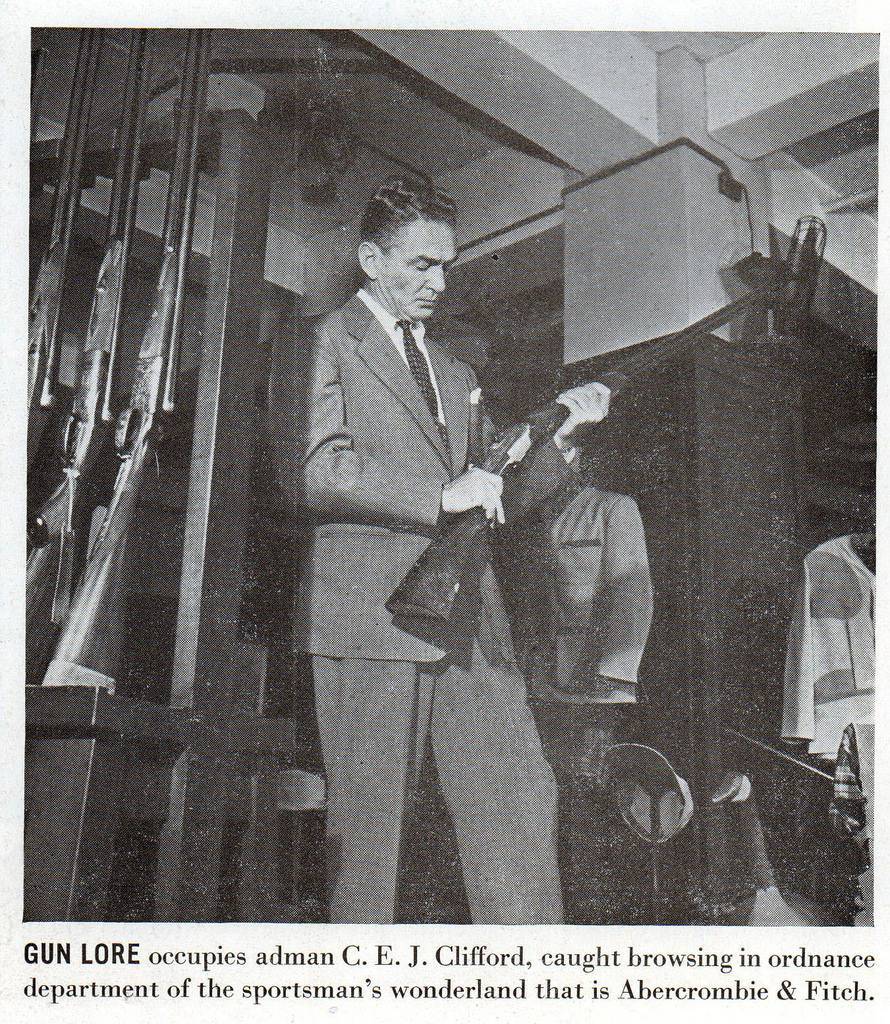

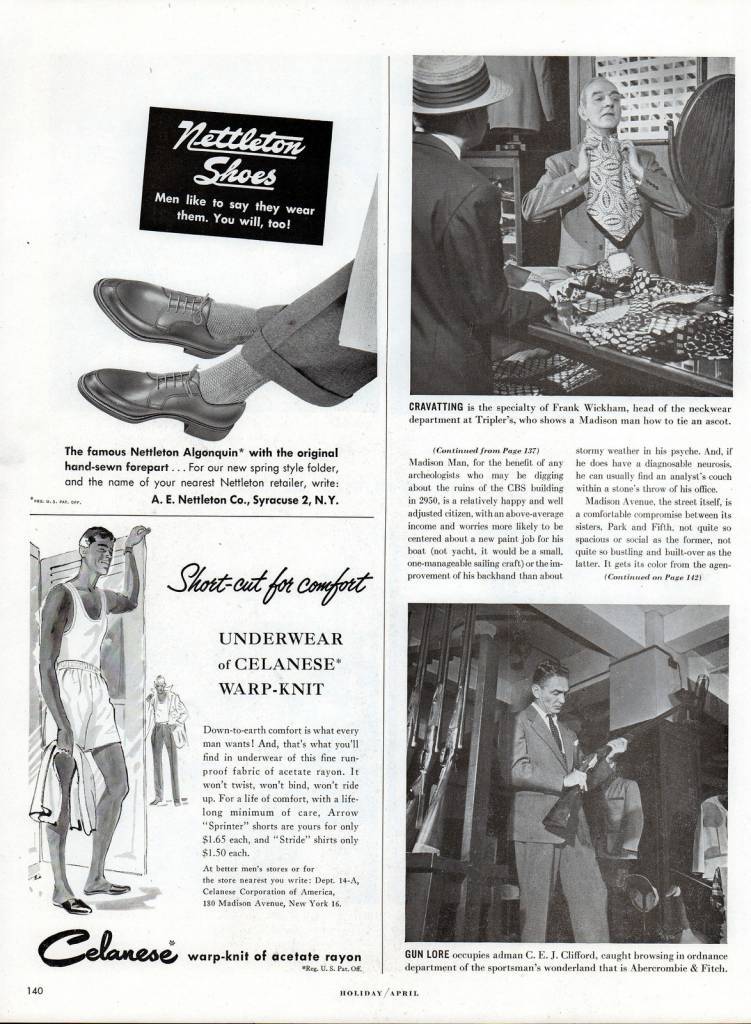

I have reprinted the article in its entirety below. Granted, it’s as much about the avenue as it is the men, but it’s a fascinating glimpse into that unique world nonetheless. I’ve also included the pictures with captions. At the end are the full pages if you’re interested.

MADISON AVENUE

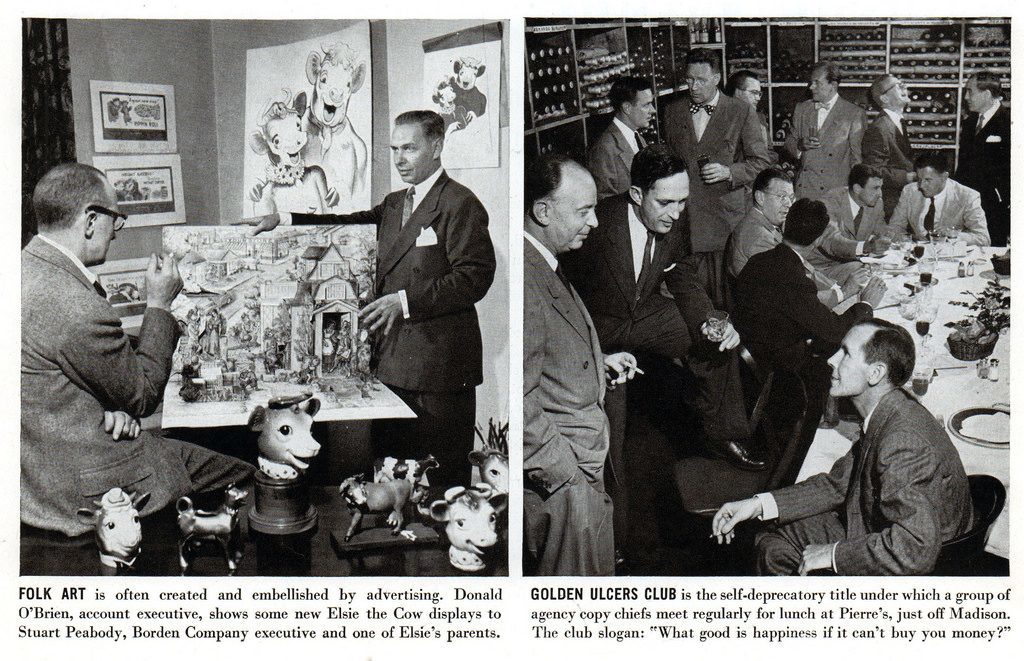

It is New York’s Advertising Row and as such it represents a sort of Dream World for the men who work on it, a world where life is as cozy and as bright as in the ads they produceADVERTISING has a folklore of its own. It has created, in the advertising pages of magazines and newspapers, a sort of never-never land where all women are beautiful, all men six-foot-two and broad-shouldered, all household chores a barrel of fun in magnificently equipped kitchens, all food prepared in a jiffy and tantalizingly delicious, where all wine is vintage, all whisky aged and all breakfast cereal crispy and crunchy and box-toppy.

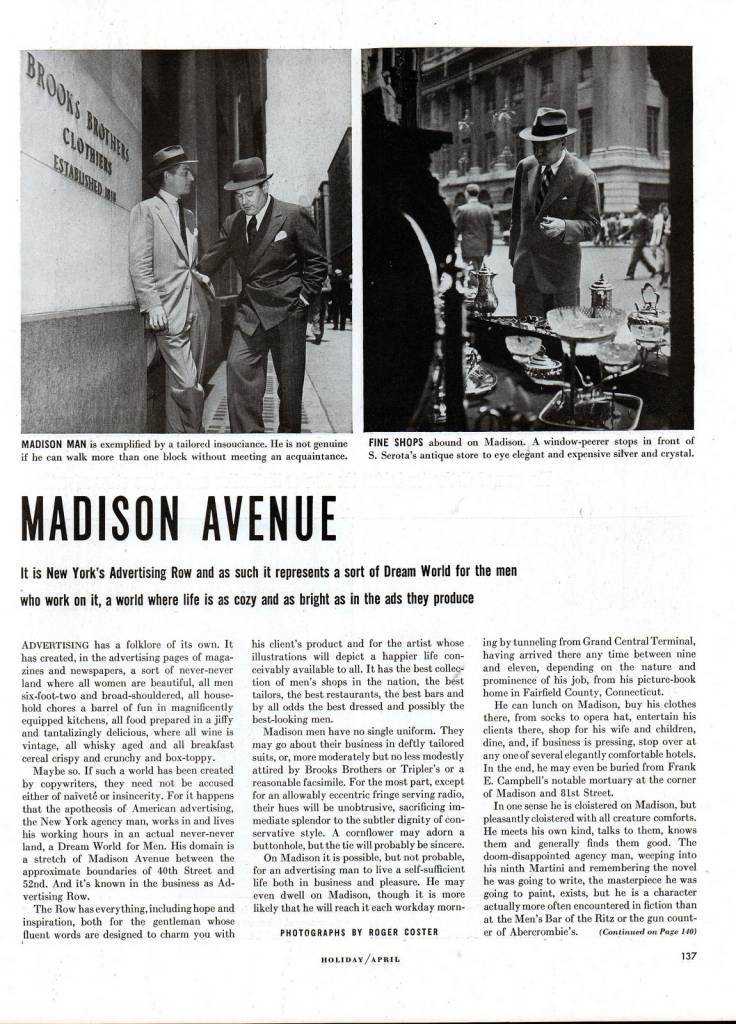

Maybe so. If such a world has been created by copywriters, they need not be accused either of naivete or insincerity. For it happens that the apotheosis of American advertising, the New York agency man, works in and lives his working hours in an actual never-never land, a Dream World for Men. His domain is a stretch of Madison Avenue between the approximate boundaries of 40th Street and 52nd. And it’s known in the business as Advertising Row.The Row has everything, including hope and inspiration, both for the gentleman whose fluent words are designed to charm you with his client’s product and for the artist whose illustrations will depict a happier life conceivably available to all. It has the best collection of men’s shops in the nation, the best tailors, the best restaurants, the best bars and by all odds the best dressed and possibly the best-looking men.

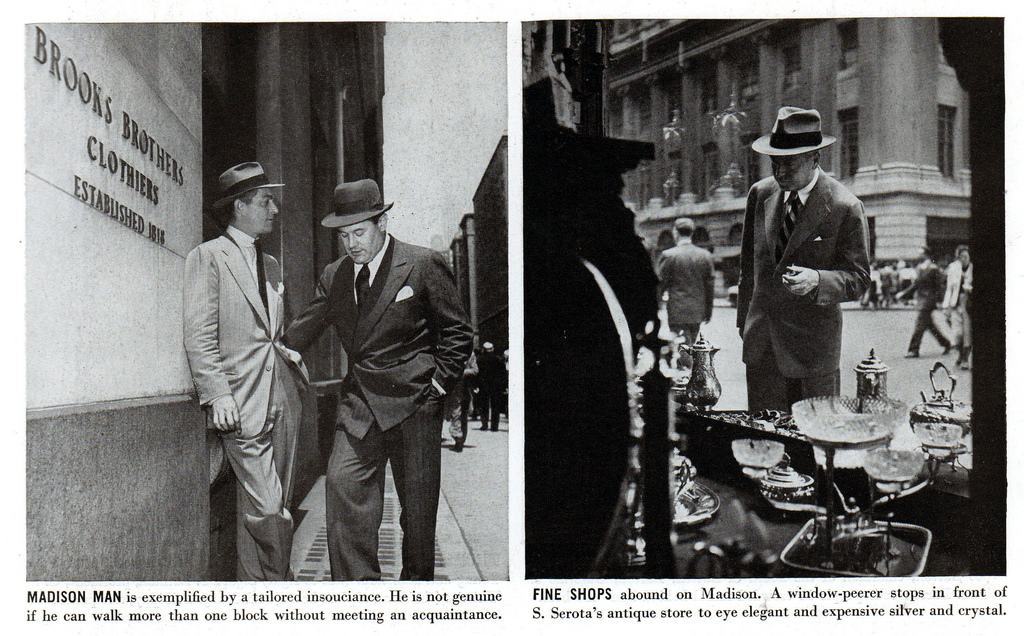

Madison men have no single uniform. They may go about their business in deftly tailored suits, or, more moderately but no less modestly attired by Brooks Brothers or Tripler’s or a reasonable facsimile. For the most part, except for an allowably eccentric fringe serving radio, their hues will be unobtrusive, sacrificing immediate splendor to the subtler dignity of conservative style. A cornflower may adorn a buttonhole, but the tie will probably be sincere.

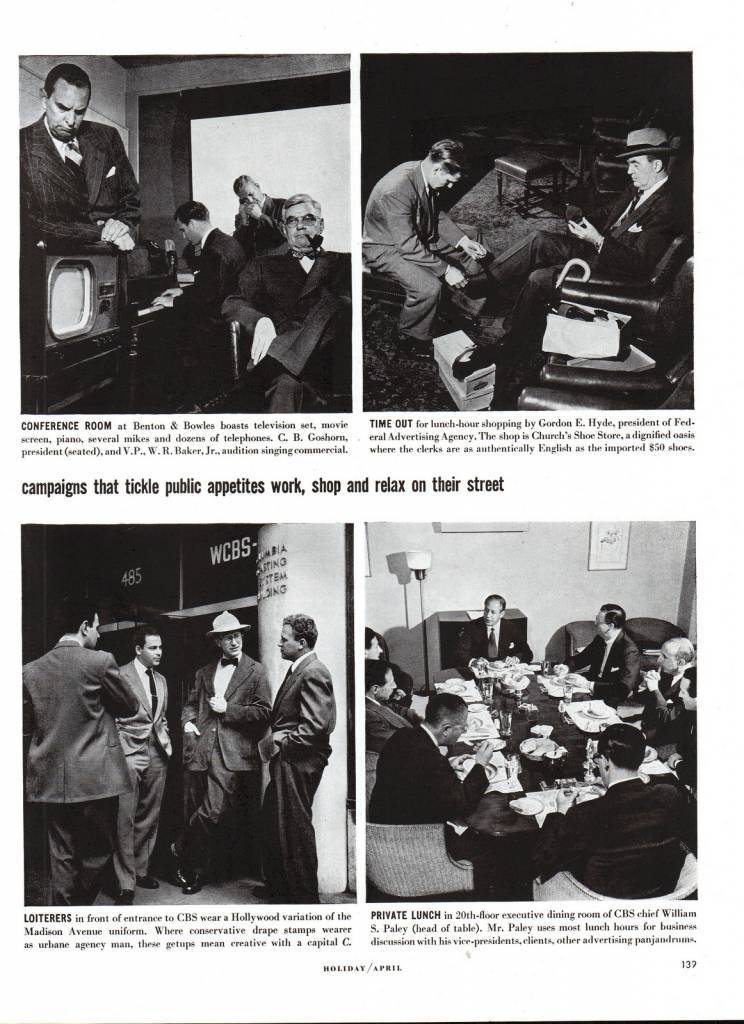

On Madison it is possible, but not probable, for an advertising man to live a self-sufficient life both in business and pleasure. He may even dwell on Madison, though it is more likely that he will reach it each workday morning by tunneling from Grand Central Terminal, having arrived there any time between nine and eleven, depending on the nature and prominence of his job, from his picture-book home in Fairfield County, Connecticut.

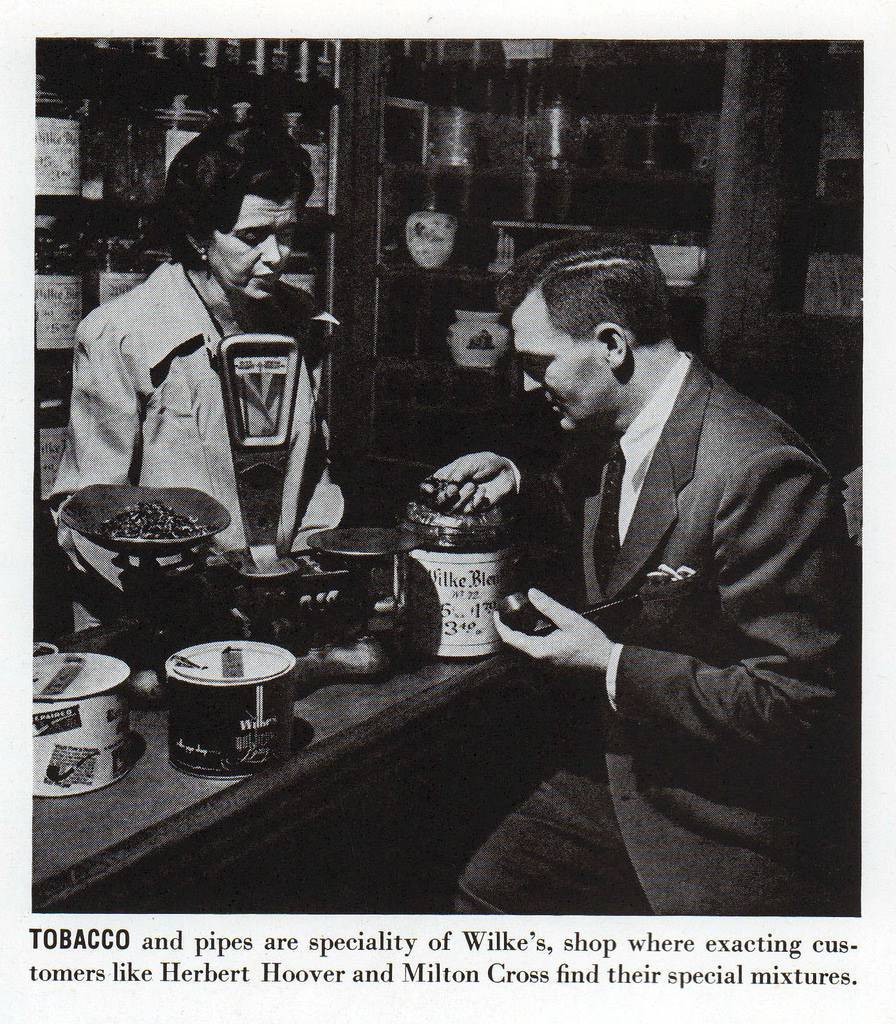

He can lunch on Madison, buy his clothes there, from socks to opera hat, entertain his clients there, shop for his wife and children, dine, and, if business is pressing, stop over at any one of several elegantly comfortable hotels. In the end, he may even be buried from Frank E. Campbell’s notable mortuary at the corner of Madison and 81st Street.

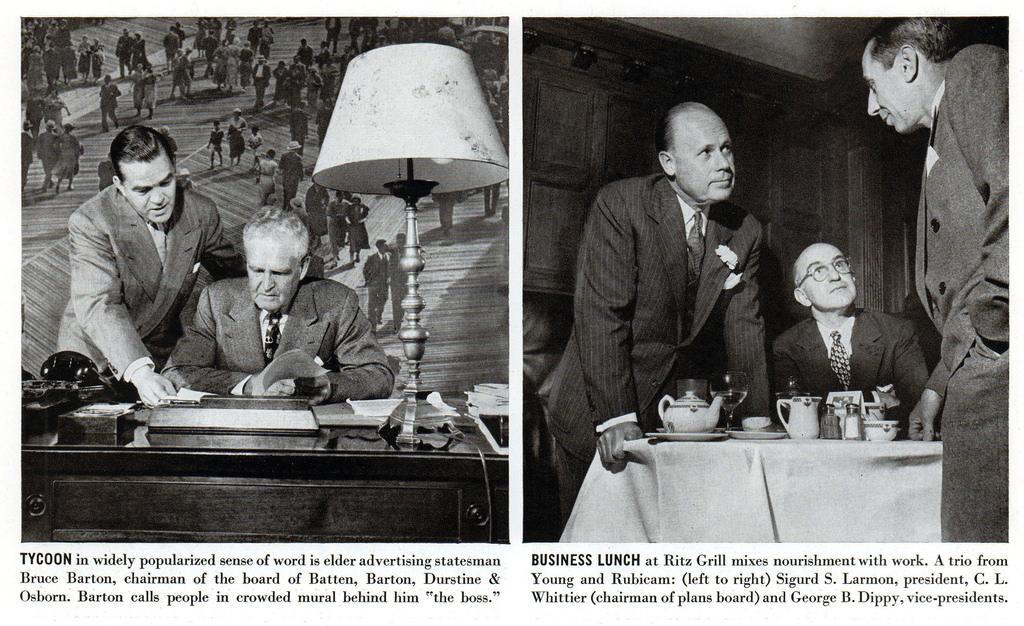

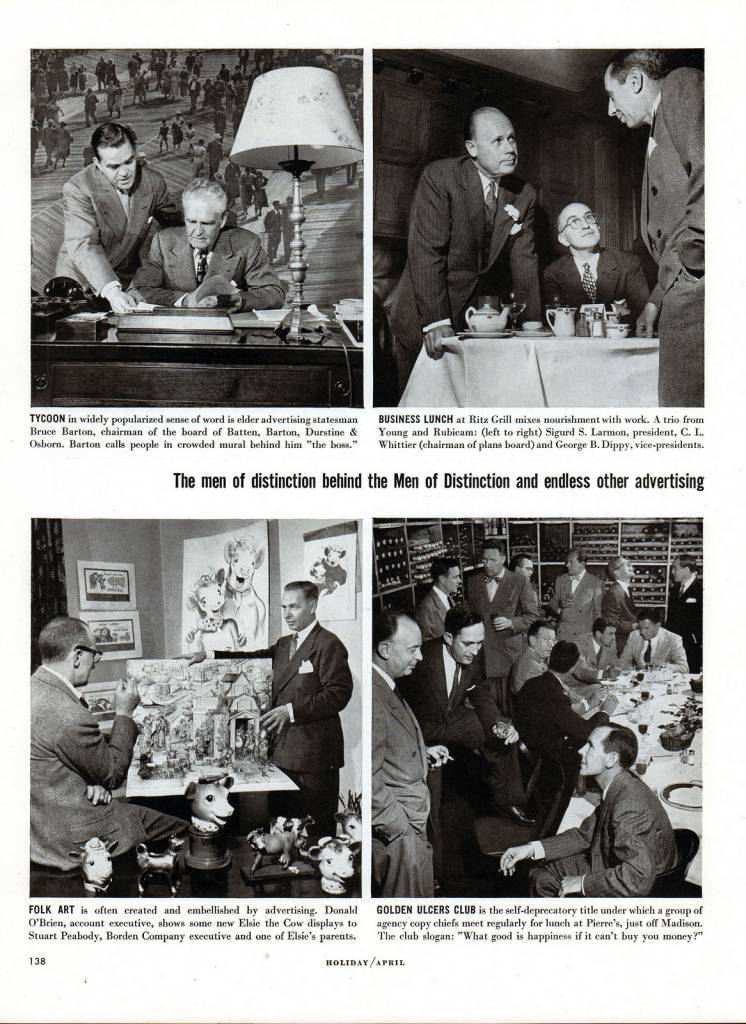

In one sense he is cloistered on Madison, but pleasantly cloistered with all creature comforts.He meets his own kind, talks to them, knows them and generally finds them good. The

doom-disappointed agency man, weeping into his ninth Martini and remembering the novel he was going to write, the masterpiece he was going to paint, exists, but he is a character actually more often encountered in fiction than at the Men’s Bar of the Ritz or the gun counter of Abercrombie’s.Madison Man, for the benefit of any archeologists who may be digging about the ruins of the CBS building in 2950, is a relatively happy and well adjusted citizen, with an above-average income and worries more likely to be centered about a new paint job for his boat (not yacht, it would be a small, one-manageable sailing craft) or the improvement of his backhand than about stormy weather in his psyche. And, if he does have a diagnosable neurosis, he can usually find an analyst’s couch within a stone’s throw of his office.

Madison Avenue, the street itself, is a comfortable compromise between its sisters, Park and Fifth, not quite so spacious or social as the former, not quite so bustling and built-over as the latter. It gets its color from the agencies, from the world of stage, screen and radio as represented by the Music Corporation of America, from radio proper in CBS, all neatly balanced for spiritual values by the presence at 50th Street of Francis Cardinal Spell-man in the Archdiocese of New York. It is a little more than 100 years old. It was officially opened as an extension of Fourth Avenue in 1836 and from its inception, its reputation, first residential, then dignifiedly commercial, has heen great.

The president and pamphleteer from whom it took the name has passed into a limbo of half remembrance. A hackie, queried as to the street’s origin, was succinctly inaccurate. “It’s from thai president,” he said, “the one that invented the Monroe Doctrine.”

The End.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.