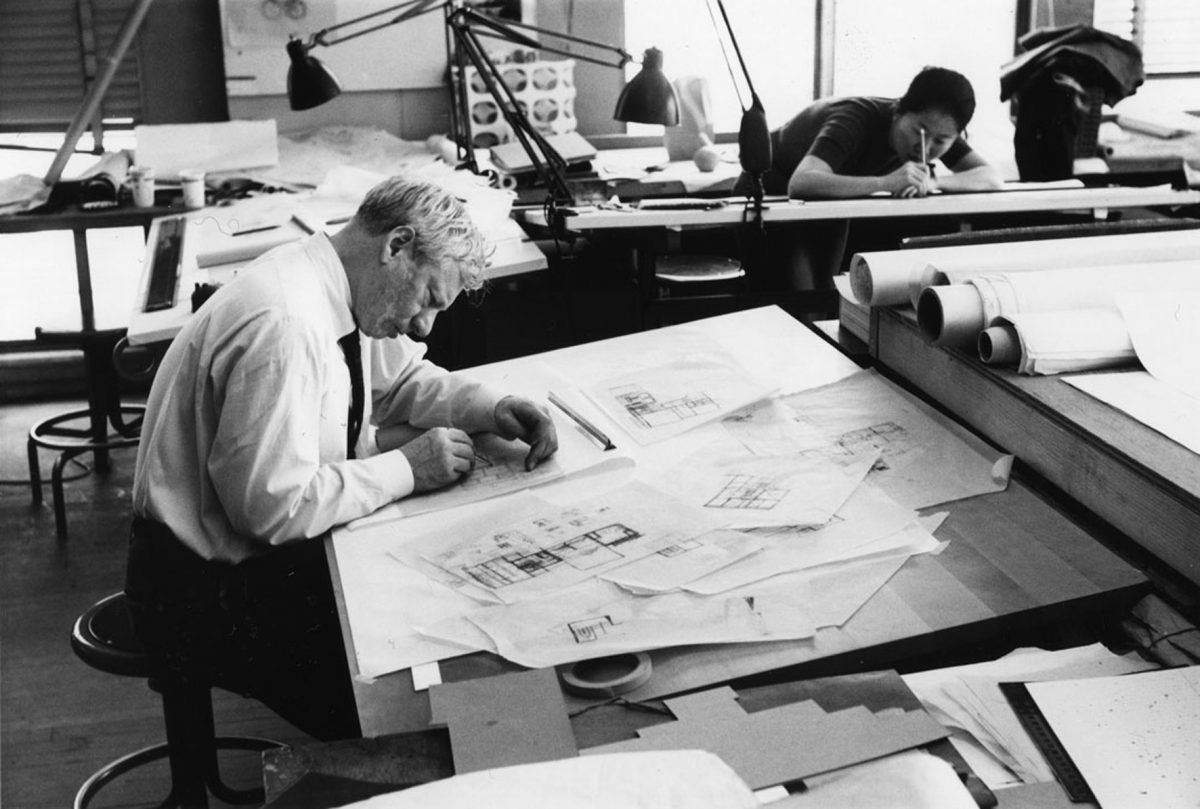

Known for his monumental brick and concrete structures, architect Louis Kahn (February 20 1901 – March 17, 1974) began his life in poverty. His family settled in Philadelphia after immigrating from Estonia and could not afford to buy him drawing materials, “so he improvised and sketched with burnt twigs and matches,” notes a Kimbell Art Museum biography. “He favored the quality of the charcoal line so much that even after he had become a celebrated architect he continued at times to draw with burnt matches.”

This anecdote speaks not only to Kahn’s determination but to the insular singularity of his vision and the indelible lines he etched into the skylines of Philadelphia, New Haven, New York, Ahmedabad, Dhaka, and La Jolla, California, where his greatest work stands, the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, “arguably the defining work of the greatest American architect,” writes Marvin Trachtenberg at Architectural Record.

Built between 1962 and 1963, the complex reflects the joint beliefs of both Kahn and Jonas Salk, discoverer of the polio vaccine, who gave the architect a brief for “a facility worthy of a visit by Picasso.” Kahn more than delivered, though he ended up building a third of his planned design, which originally included not only the laboratory complex but a meeting hall and living space. The innovations of his poured concrete design include laboratory floors that alternate with utility floors, to minimize disruptions to scientific work while repairs and maintenance went on. Arch Daily’s Luke Fiederer writes:

The laboratories of the Salk Institute, first conceived as a pair of towers separated by a garden, evolved into two elongated blocks mirroring each other across a paved plaza. The central court is lined by a series of detached towers whose diagonal protrusions allow for windows facing westward onto the ocean. These towers are connected to the rectangular laboratory blocks by small bridges, providing passage across the rifts of the two sunken courts which allow natural light to permeate into the research spaces below.

The Institute’s open plan allows “different departments to circulate among study towers,” notes Curbed, a central feature “cited by the Salk’s scientists as influential to their research” into “neurobiology, genome mapping, and stem cell research.” The Salk, whose motto is “Where Cures Begin,” is also a monument to the end of a devastating epidemic that killed and disabled millions around the world in the first half of the 20th century before Salk’s vaccine ended the virus in the 1950s.

In 1960, when Salk received funding for the Institute from the March of Dimes, he also began campaigning for mandatory vaccination, considering it a “moral commitment” to the public’s health. Salk wanted the Institute to reflect his ideas about science as a broadly humanist public enterprise. His instructions also had religious undertones. “Kahn’s scheme for the Institute is spatially orchestrated in a similar way to a monastery,” Fiederer writes, inspired by the Monastery of St. Francis of Assisi, “an example for which Salk had previously expressed his admiration.”

The Salk represents a secularization of the monastic ideal: both the research institute and the monastery subsist on endowments, political largesse, and reputation. The Salk’s purpose has been to carry knowledge about the natural world forward—it is not only a cloister but a temple to research, one that architecturally recalls “gardens of Mughal India and Renaissance villas like Tivoli and the Villa Lante,” Trachtenberg writes, “an inspired synthesis and reformulation that never disappoints.” In these photos, you can see the complex respond to the Southern California light, and see its teak window frames in both their unrestored and restored state after a lengthy effort by the Getty to remove their discoloration.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.