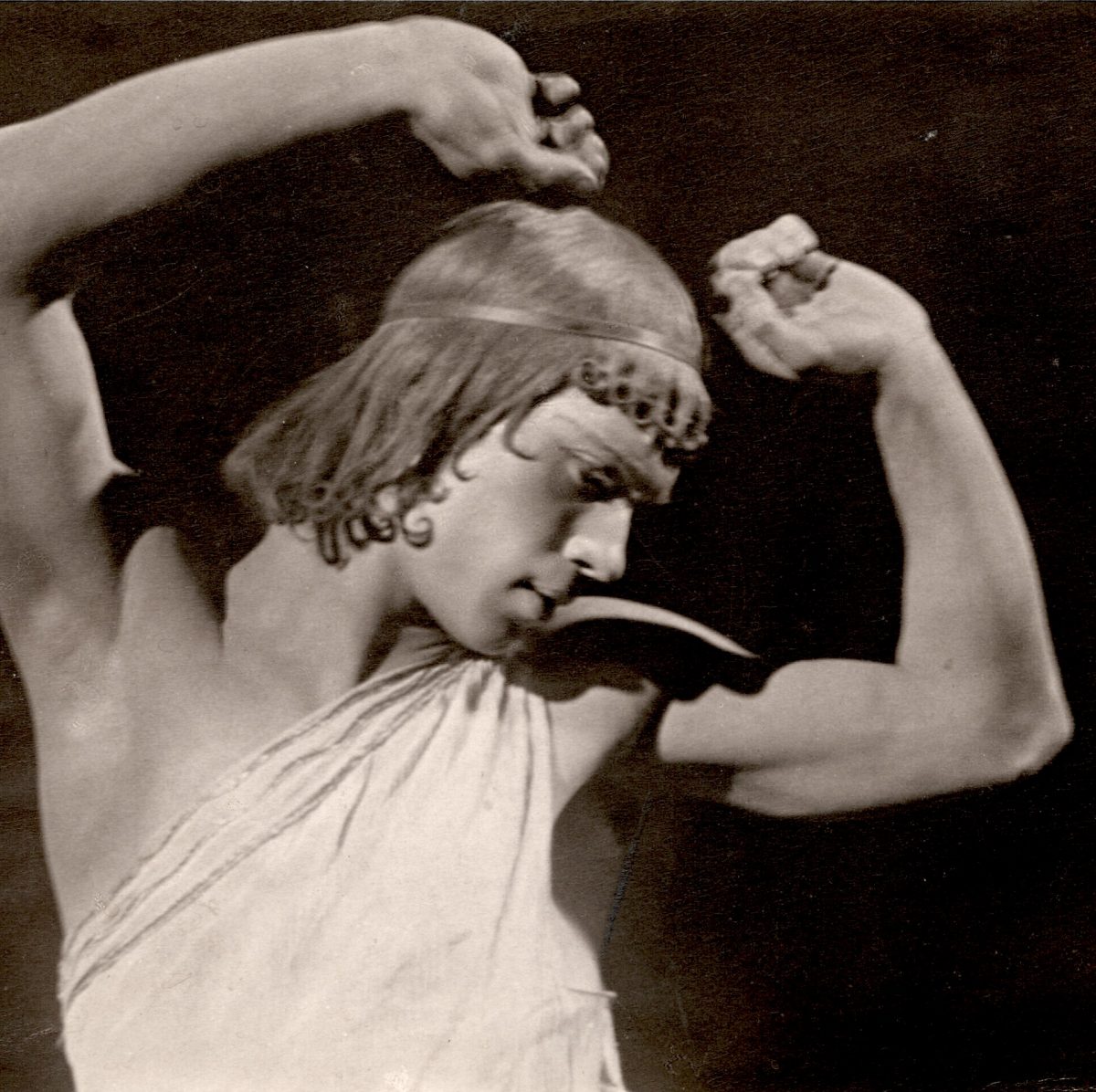

Vaslav Nijinsky in Narcisse, 1911

“I am God in a body,” wrote Vaslav Nijinsky (1879-1944) in his famous Diary. “Everyone has this feeling, but no one uses it.” Nijinsky used the feeling until it took him over. Born into a family of Polish dancers, he joined Serge Diaghilev’s groundbreaking traveling company, Ballet Russes, in 1909 and became an worldwide sensation in his first season. In 1912-1913, he worked with his sister, Bronislawa Nijinkska, choreographing the controversial production of Debussy’s L’Apres-midi d’un faune and the riotous performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.

That same year, Nijinsky was fired from Ballet Russes after he broke off his affair with Diaghilev, married Hungarian aristocrat Romola de Pulszky and settled to down to start a family, a domestic arrangement forbidden to all Ballet Russes dancers. (See his wedding photo further down). Nijinsky continued his choreography, but by 1919, his career seemed in shambles after attempts to form his own company floundered. He suffered a mental health crisis and was committed to an asylum in Switzerland, diagnosed with schizophrenia at the age of 29. He would spend the next 30 years in confinement, never to dance on stage again.

Serge Diaghilev, Vaslav Nijinsky, and Igor Stravinsky

The Diary, “written in six and a half weeks, from January 19 to March 4, 1919,” was not published until 1936, “in a drastically expurgated English edition,” notes editor Joan Acocella. Begun on the morning of his final public performance at the Suvretta Hotel in St. Moritz, Switzerland, the pained memoir “is the only sustained, on-the-spot (not retrospective) written account, by a major artist, of the experience of entering psychosis.” Throughout the work, Nijinsky documents his struggle against an enemy he variously refers to as “the mind,” “death,” and “stupidity”—terms for a terrifying spiritual paralysis he seemed to encounter everywhere.

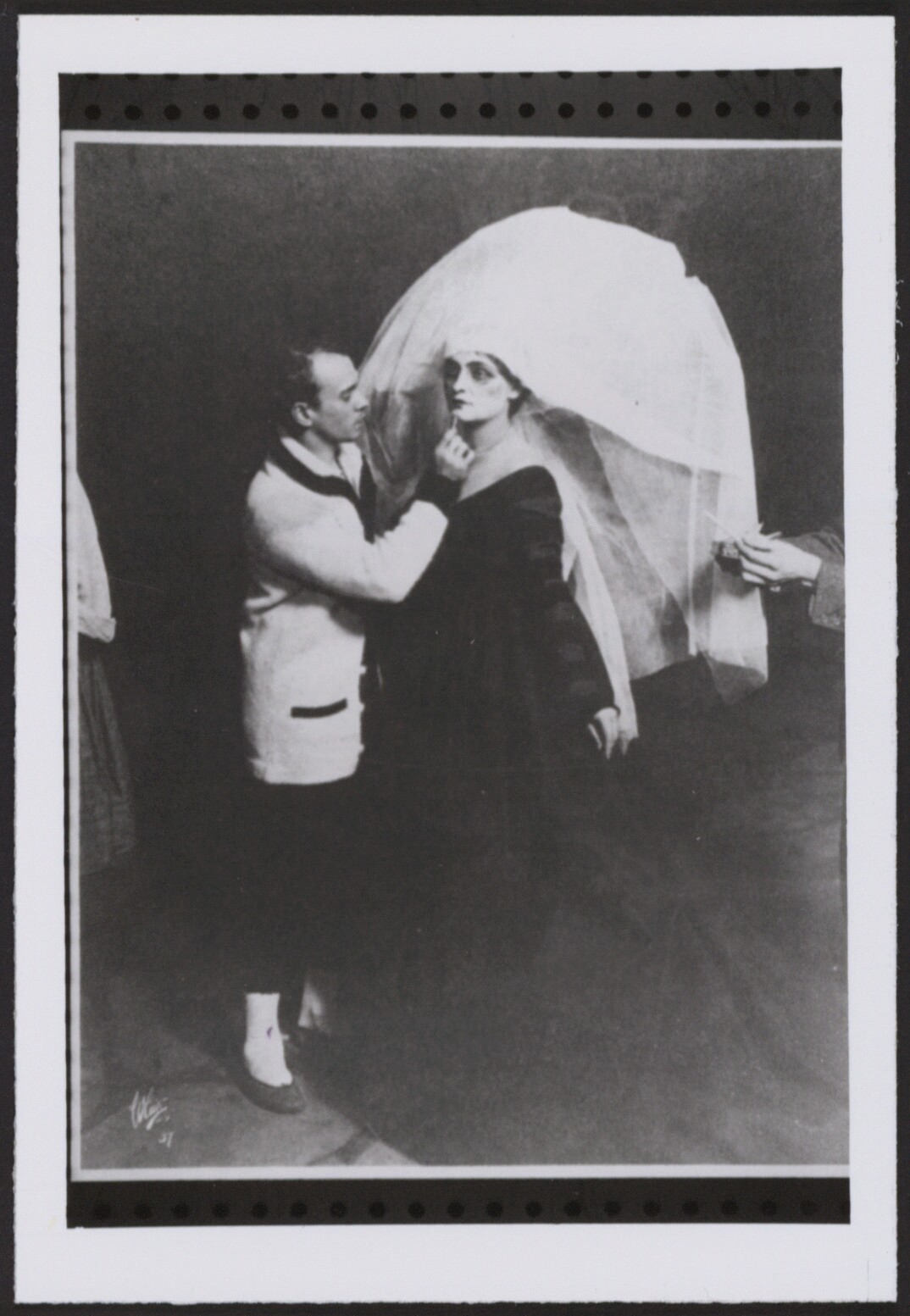

Vaslav Nijinsky and Romola de Pulszky on their wedding day, 1913

In his legendary 1956 existentialist study, The Outsider, Colin Wilson placed Nijinsky’s Diary next to the work of Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Camus, and Kierkegaard. The dancer reached “a limit of sincerity” beyond any of them in his passionately vulnerable attempts to cut through social convention and his deteriorating mental state and connect directly with his source of self-actualization. And yet, Nijinsky could only connect—with life, the divine, himself, and others—through dance.

Nijinsky’s kingdom was the body. People who saw him dance have testified to his amazing ability to become the part he was acting, whether the Negro in Scheherazade, the puppet in Petrushka, or the Prince in Giselle. His discipline gave him the power to dismiss his identity at will, or to expand some parts and contract others to give an illusion of a completely new personality. It was this power that, at times, became a mystical intensity of abnegation in his dancing, that occasionally gave him glimpses of the ecstasy of the saint.

Nijinsky’s ability to disappear into a role went far beyond performance, “and herein lies the cause of his breakdown,” Wilson argued: an overidentification with other people’s suffering. “Always, there is the tearing, excoriating demand, of pity. It is the worst of Nijinsky’s problems.” The Diary is filled with expressions of anguish—the pain of being unable to properly express his state of mind. “I want to say so much and cannot find the words,” he writes.

Wilson remarks that “dancing is his natural form of self-expression, but outside dancing, [Nijinsky] meets all the Outsider’s usual problems…. While he could dance regularly, every day, and restore contact with the vital, instinctive parts of his own being, Nijinsky could not go insane. Sanity lay in creation.” Perhaps his early success only delayed the inevitable onset of a condition he could not escape. But Nijinsky himself ascribed his loss of sanity to the suffering of creative stagnation. “I am a man of motion,” he wrote, “not of immobility.”

Vaslav Nijinsky, 1900

The intense religious fervor of his language—in which he seems, Wilson writes, “obsessed with the idea of becoming God”—can also be seen as the devout Catholic’s only literary means of expressing the inexpressible: the incredible power he feels in a wordless physical state, his sole source of purpose and meaning. “I am feeling through flesh,” Nijinsky wrote, “and not through the intellect.” Lucid statements like this alternate with expressions of deep misery and wildly ecstatic phrases in which he proclaims, “I am God, I am God, I am God.”

There are many ways to describe Nijinsky’s god, invoked over and over on every page of the Diary. But it seems, above all, to be the name he gave to the creative energy he embodied, and without which he was forever lost.

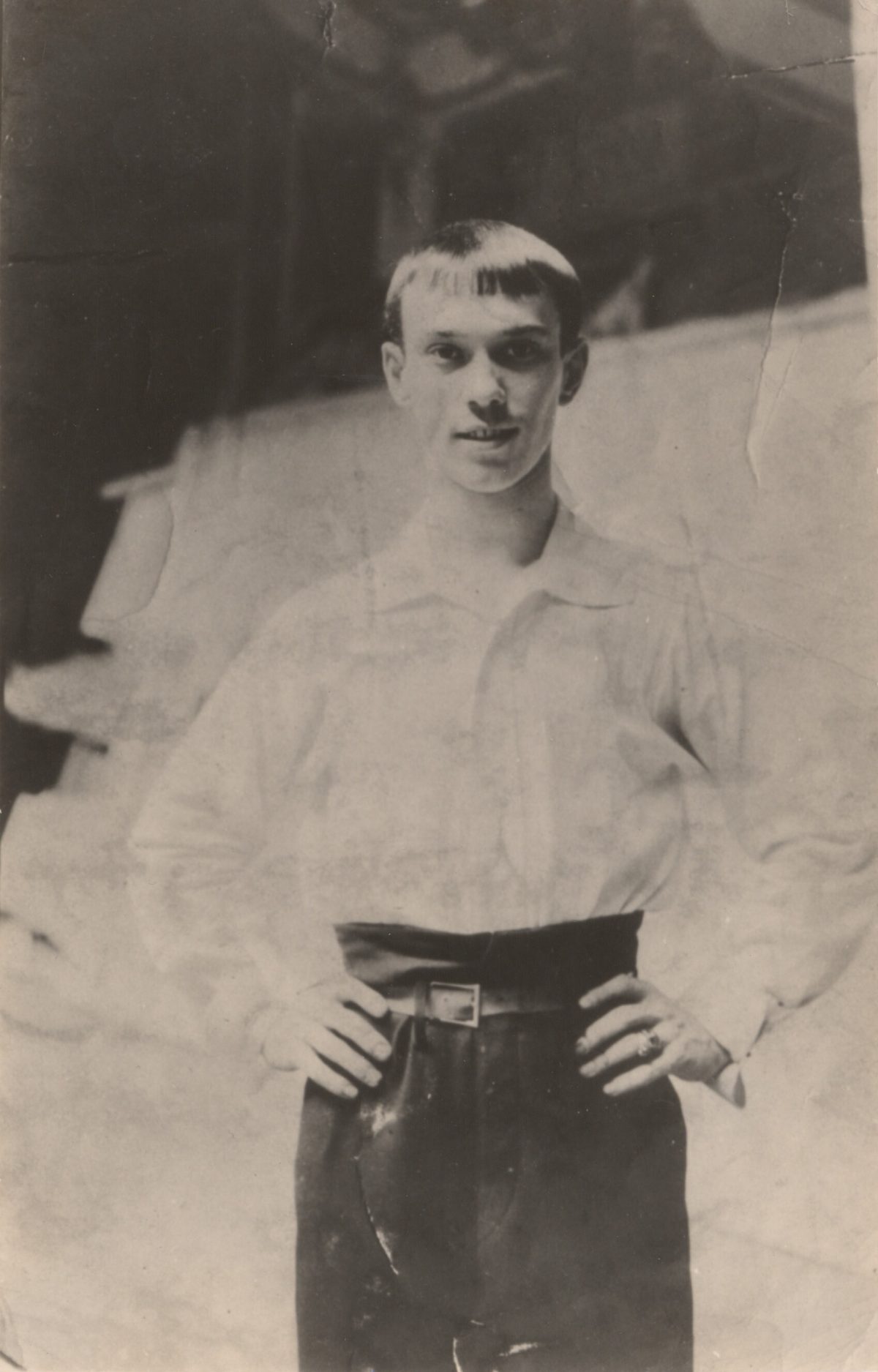

Nijinsky in practice clothes, 1908

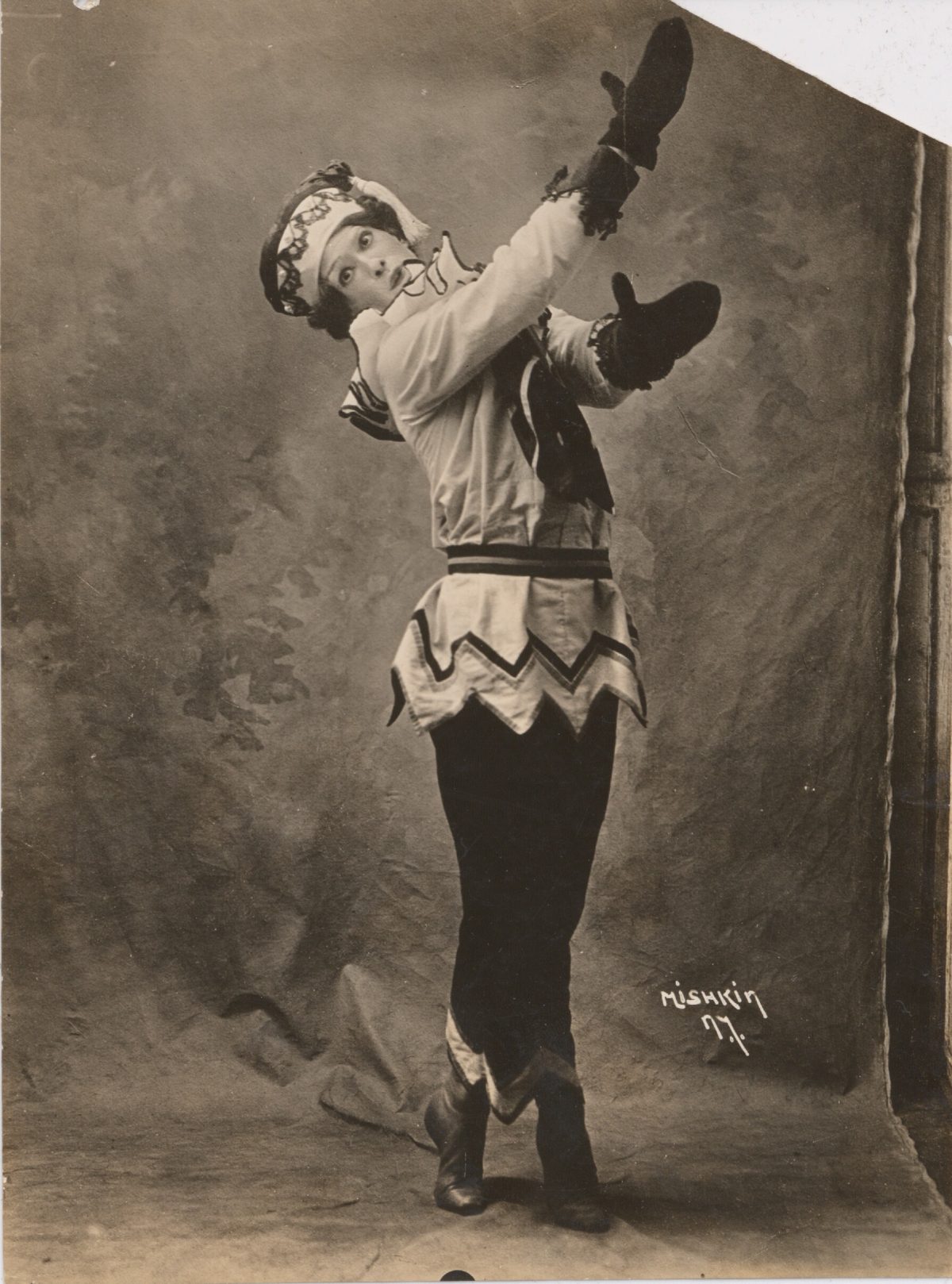

Vaslav Nijinsky in Pavillon d’Armide, 1909

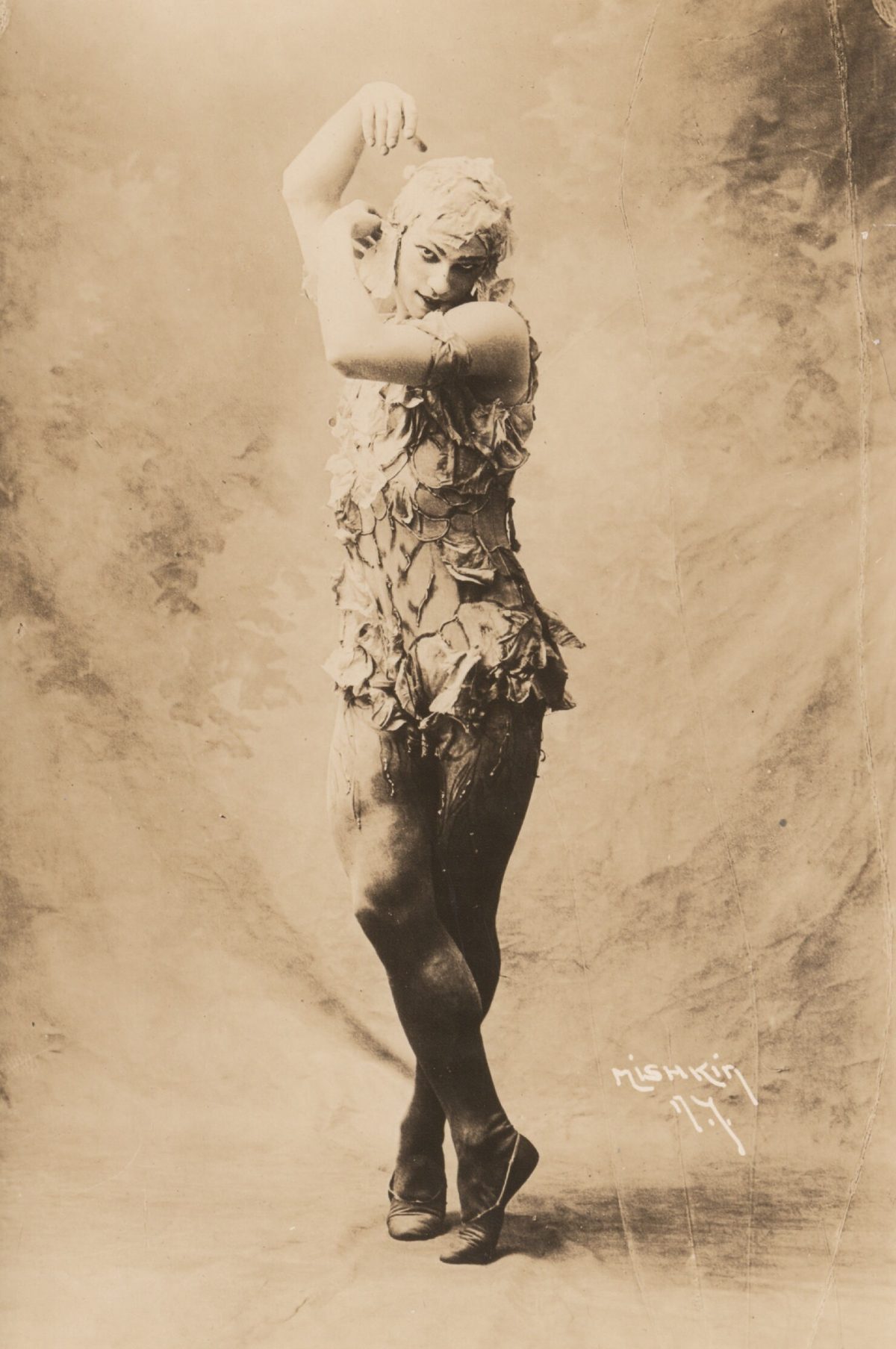

Vaslav Nijinsky in Scheherazade, 1910

Vaslav Nijinsky in Le Spectre de la Rose, 1911

Vaslav Nijinsky in Petrushka, 1911

Nijinsky applies makeup to a performer, 1916

All images via the Library of Congress Digital Collections

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.