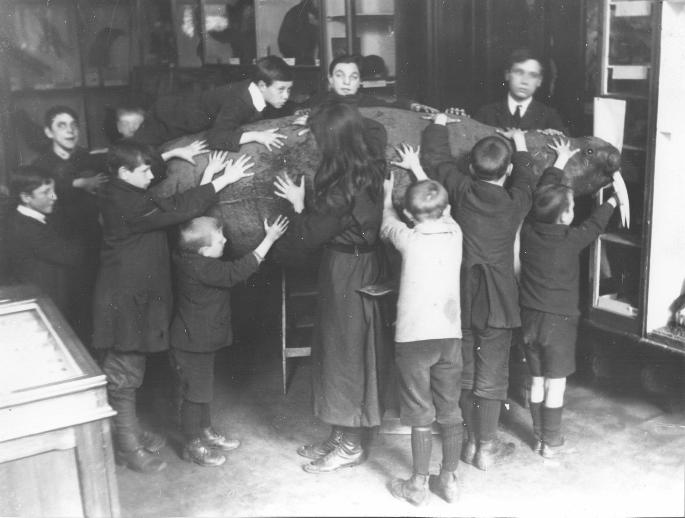

One Sunday afternoon in 1913 a group of blind children from Sunderland Council Blind School were invited to feel the animals at Sunderland Museum, so they could ‘see’ what they looked like. The museum’s message was unusual: do touch the artefacts.

The trip was organised by John Alfred Charlton Deas, a former curator at Sunderland Museum. The show were a success, running for children and adults from 1913-1926.

In a document written by Charlton Deas titled What the Blind May ‘See’: Some Museum and Other Experiments in Tactile Sight, he speaks of a teacher called Mr G. I. Walker who expressed the difficulty of blind children in understanding the concepts of size. He stated:

“However carefully the children were informed that their small model of a cow was only one-fortieth the size of the real animal, they were unable to think of the cow as anything larger then the model.”

This is because unless they have had actual tactile contact with something, there is “no standard of size, form and texture” to relate it to. Charlton goes on to share an instance that he came across when a young blind boy had recovered his sight after having an operation. He said:

“For several days following, he went about in a state of surprise and fear, for almost everything which he had not frequently touched, differed in size from his recollections of seven years previously.”

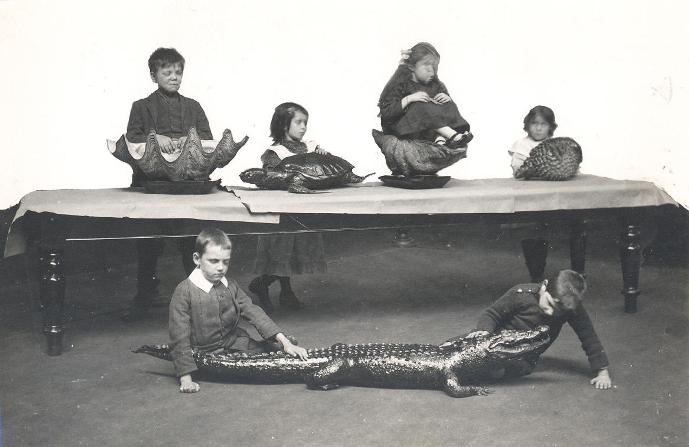

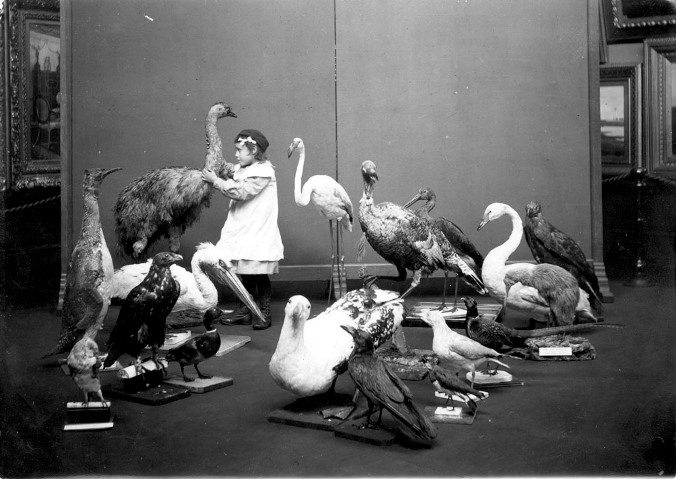

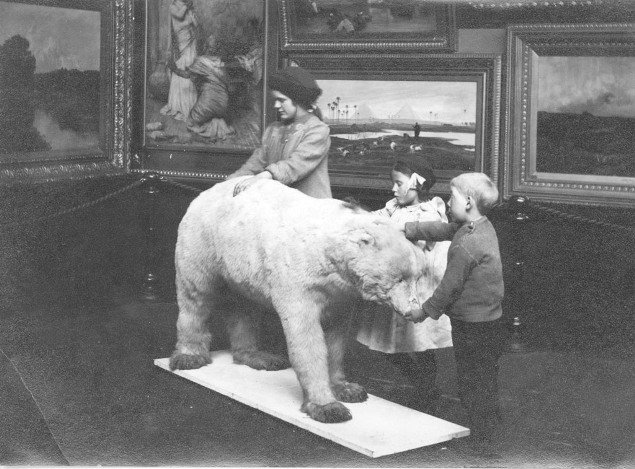

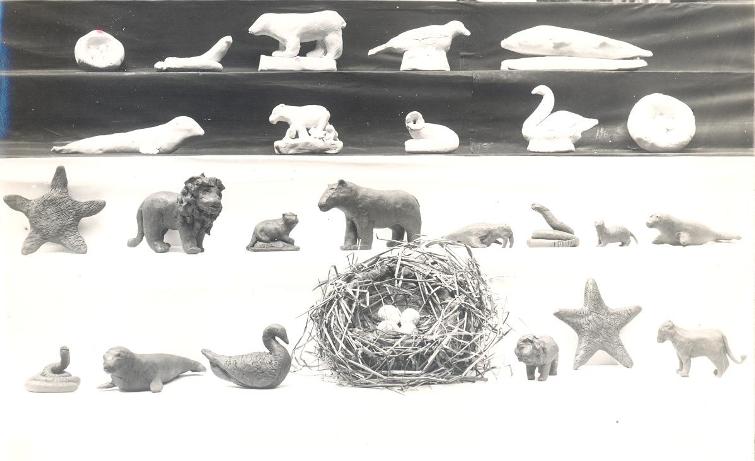

Dr. H. K. Wallace (a local zoologist) gave a brief lecture for the first natural history Sunday session, which visitors examined a chimpanzee, lion, lioness and cubs, tiger, polar bear, badger, otter, wolf, seal, walrus and many others.

In July 1913 Deas read a paper at the Museum Association conference in Hull on the theme of The Showing of Museums and Art Galleries to the Blind.

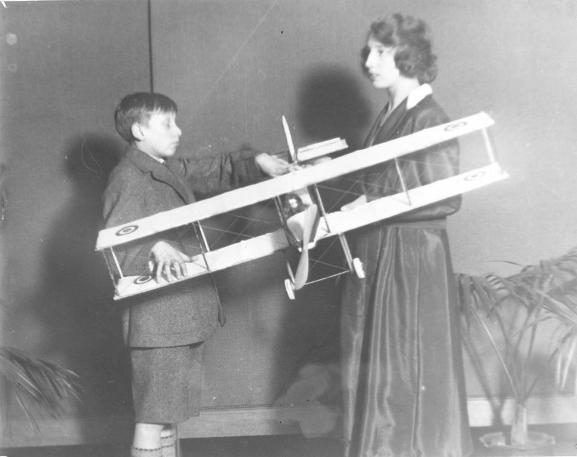

The talk was illustrated with photographs, lantern slides and a selection of models made by children. It described in detail experiments he had undertaken in the museum to help alleviate ‘the long night of those who live in perpetual darkness.’ Deas initially had focused his attention on working with the adult blind and organized five handling sessions accompanied by related lectures. The sessions lasted three hours and took place on Sunday afternoons when the museum was closed to the general public and ‘the privacy desirable for such experiments was thereby secured.’ The focus of the first tactile session was the art gallery, but began with a description of the ‘dimensions and arrangements’ of the art gallery. The length and breadth of the room was given in the number of paces, the height of the room, the lighting arrangements, the method of hanging and protecting the pictures were also described.

Deas commented:

[…] these details may at first seem trivial, but a knowledge of surroundings, relative proportions and “atmosphere” generally, is as important and interesting to the sightless as to the sighted, who are apt to overlook the fact through unconscious familiarity (DEAS, 1913).

The participants were then given a small painted and unpainted canvas, an artist’s palette, brushes, and paint tubes to ‘feel and examine’. The use of all of these was explained and then the participants were taken into the gallery and presented with some glazed images, which were examined for size, the content of the painting was described, and the most important features were indicated ‘by guiding the first finger of the person’s hand over the outlines.’

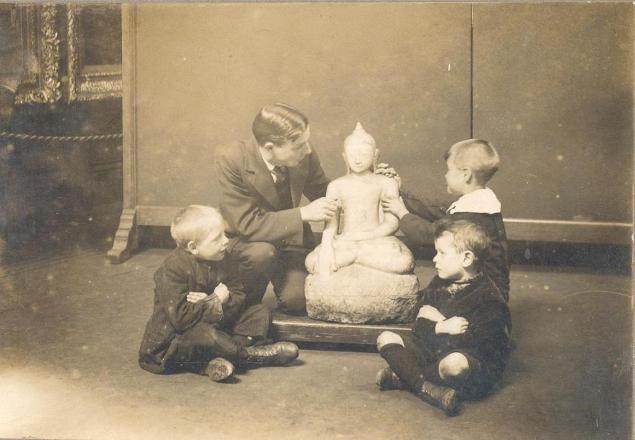

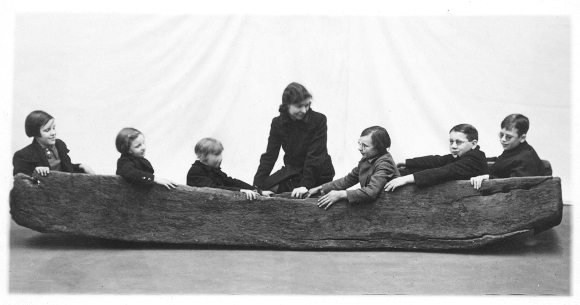

The subsequent demonstrations after the ‘Picture Sunday’ were taken up with handling museum objects from the Natural History collection along with listening to contextual lectures. A final session consisted of handling miscellaneous objects including a ‘Burmese Idol’, prehistoric implements, armour, Zulu Shields, models of different types of ships, a model of a Locomotive and ‘Busts of Celebrated Men.’ T

he same programme was then introduced for blind children from the Council School on consecutive Monday mornings when the museum was closed for three hours. The children used their hands with ‘great dexterity’, which occasioned Deas to remark in his lecture that ‘touch is the first sense which a child develops’ and to quote Maria Montessori’s comment that her blindfolded children were ‘proud of “seeing” without eyes’ and holding up their hands and crying ‘Here are my eyes, I can see with my hands.’

Some of the children produced clay models based on the collections that they had handled at the museum. Ranging from 8 to 15 years old, these blind children created these models 5 weeks after their visits, some without any previous experience in handling clay. These were then displayed at Sunderland museum in cases along with photographs of their visit

Was taxidermy ever more useful?

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.