Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government came to power with the express intent of waging, and winning, a war on organized workers. According the Thatcher’s biographer Charles Moore, upon taking office in 1979 she immediate announced to home secretary Willie Whitelaw, “the last Conservative government was destroyed by the miners’ strike. We’ll have another and we’ll win.” The British Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 was a result of that intention.

The strike was orchestrated partly in retaliation for the strikes of 1972 and ’74, and it was provoked strategically over several years. “If there was to be a strike,” Moore writes, the government decided “it should begin in the spring and… be over pit closures, which tended to divide the union, rather than over pay, which tended to unite them.” That’s exactly what happened in 1984, when NCB chairman Ian MacGregor announced a plan to close, on “economic” grounds, “about 20 pits over the next year,” Donald Macintyre writes at the New Statesman, “at a cost of 20,000 jobs.”

The original plan, Thatcher later admitted in her memoirs, had been cut 75,000 jobs over three years in order to privatize coal. Though the government publicly claimed the industry was no longer profitable, they had stockpiled coal and oil reserves, and demanded that the mines keep producing throughout the year-long strike.

MacGregor’s announcement was met with the expected response. Strikes began to spread, first in Yorkshire and Scotland, then to “81 of the country’s 163 pits by 12 March.” The government and media on both the left and right wasted no time in framing the labor crisis as a war—between unions and “right to work” miners, and between disgruntled unionists and police, representatives of law and order whose actions would be framed by right-leaning media as noble and necessary.

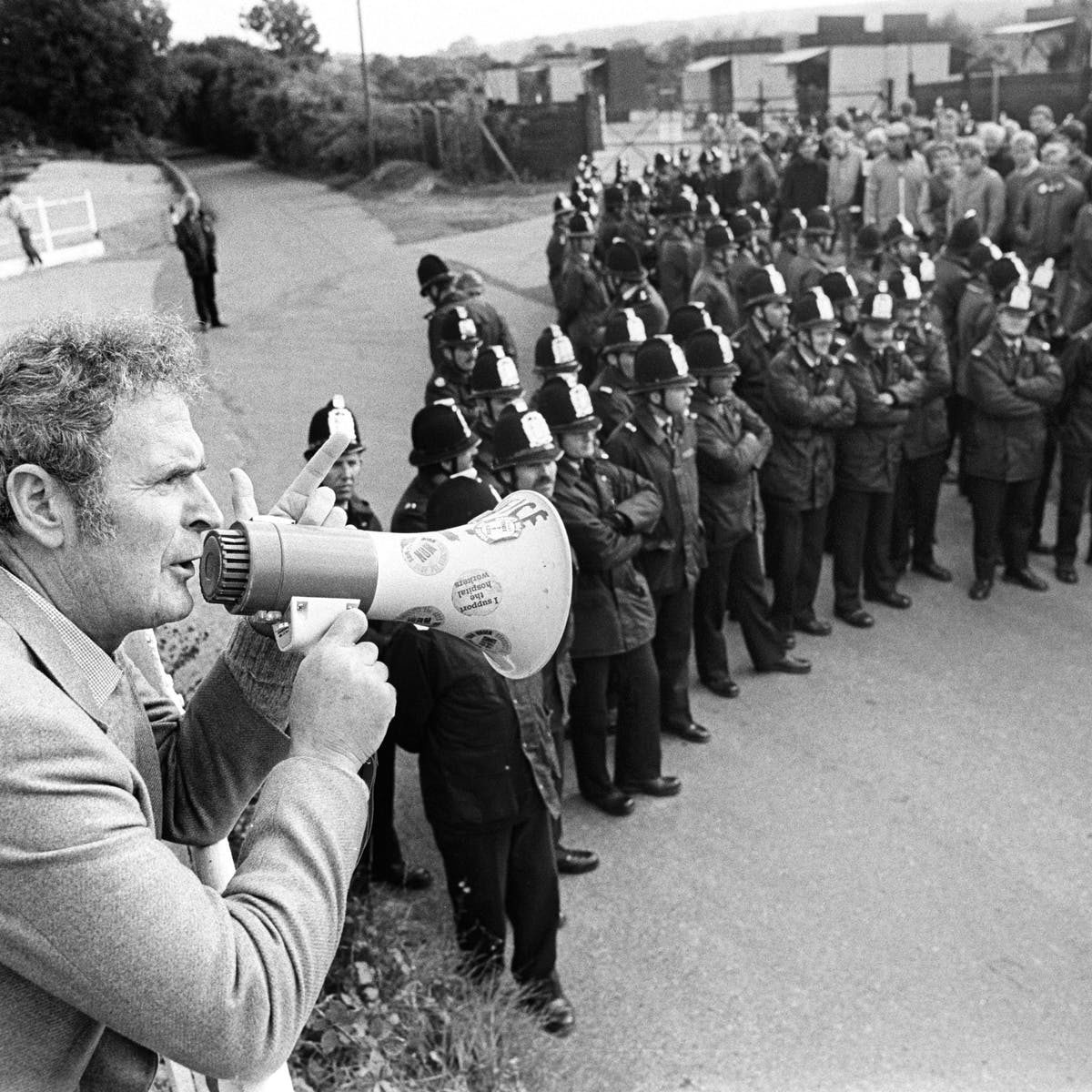

Thatcher referred to firebrand National Union of Mineworkers president Arthur Scargill (above) as “the enemy within.” The press began a campaign that overwhelmingly relied on metaphors of war. “Police and striking miners were both depicted as soldiers,” notes one thorough analysis of the coverage. “With war providing a structuring frame… events within the strike become conceptualized as ‘battles.’…. In fact, this was a persistent discursive practice in relation to instances of violence across the media and throughout the strike.”

Military roles get assigned to participants with Scargill fulfilling the role of a ‘general’ or ‘dictator’; negotiations between Government, the Coal Board and the NUM are construed as ‘peace talks’; and the miners agreeing to return to work is seen as an act of ‘surrender’ marking ‘defeat’ for the NUM…. [Even] the left-leaning Daily Mirror, and the socialist newspaper The Morning Star… maintained a war framing by invoking aspects of the frame.

Despite the invocation of “peace talks,” it was not implied that the Government had played any part in making war on its citizens. The divide and conquer strategy was employed right away, pitting the NUM against the Union of Democratic Mineworkers, who aligned with the Tories, resisted the strike, sent in scab workers, and (recently uncovered documents reveal) were in secret talks with Thatcher all along. A particularly unsubtle headline from The Sun the month the strike began shows an angry woman waving a toy pistol. The headline “Pit War,” announces violence erupting “on the picket line as miner fights miner.”

Keith Pattison served as the official photographer for striking NUM workers in East Durham, spending eight months documenting the pit village of Easington Colliery. “There was an intense frustration on the ground as, from day one,” he says, “there was an extraordinary level of support for the strike not just from Labour Party members and union members, but from the general public as a whole, all over the country. But the mainstream media were continually mis-representing how things were on the picket lines.”

The papers made Scargill “a hate figure, comparing him to Hitler and all sorts.” Scargill’s press officer Nell Myers fired back in a 1985 Guardian interview: “The industrial correspondents, along with the broadcasting technicians, are basically our enemies. Responsible for… a cyclone of vilification, distortion and untruth.” Battle lines drawn, the drama played out in the papers and on the news. As violence intensified during sporadic confrontations, the war metaphor became increasingly literal.

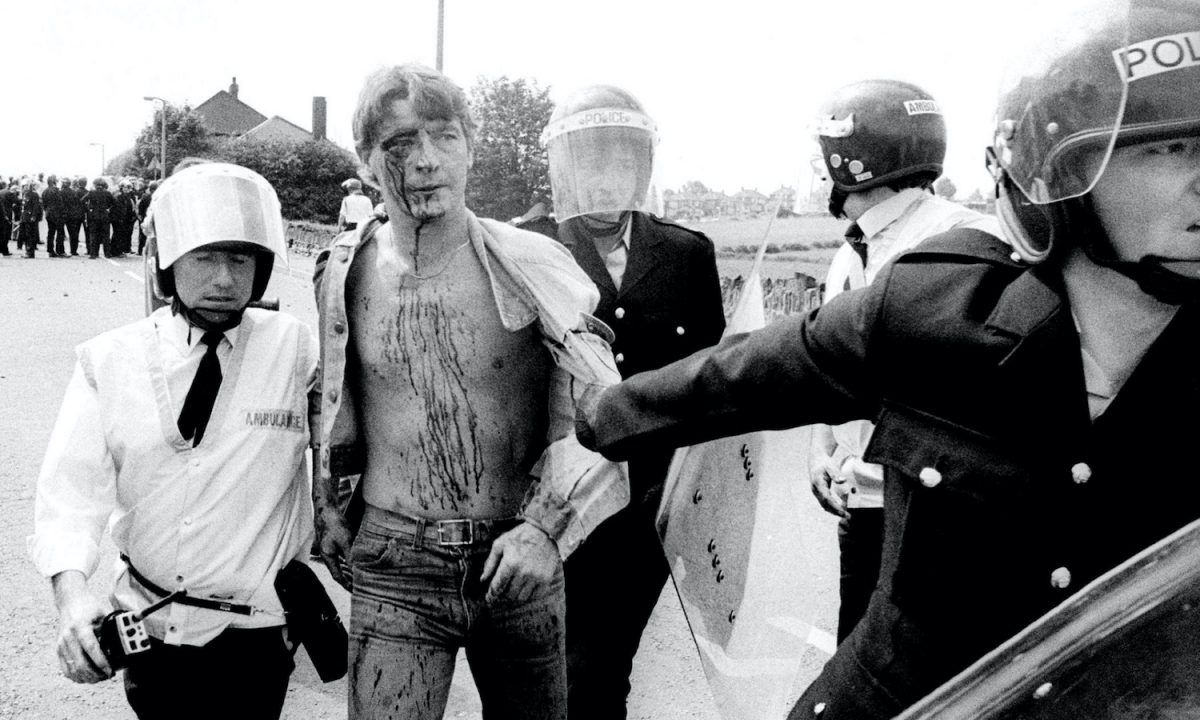

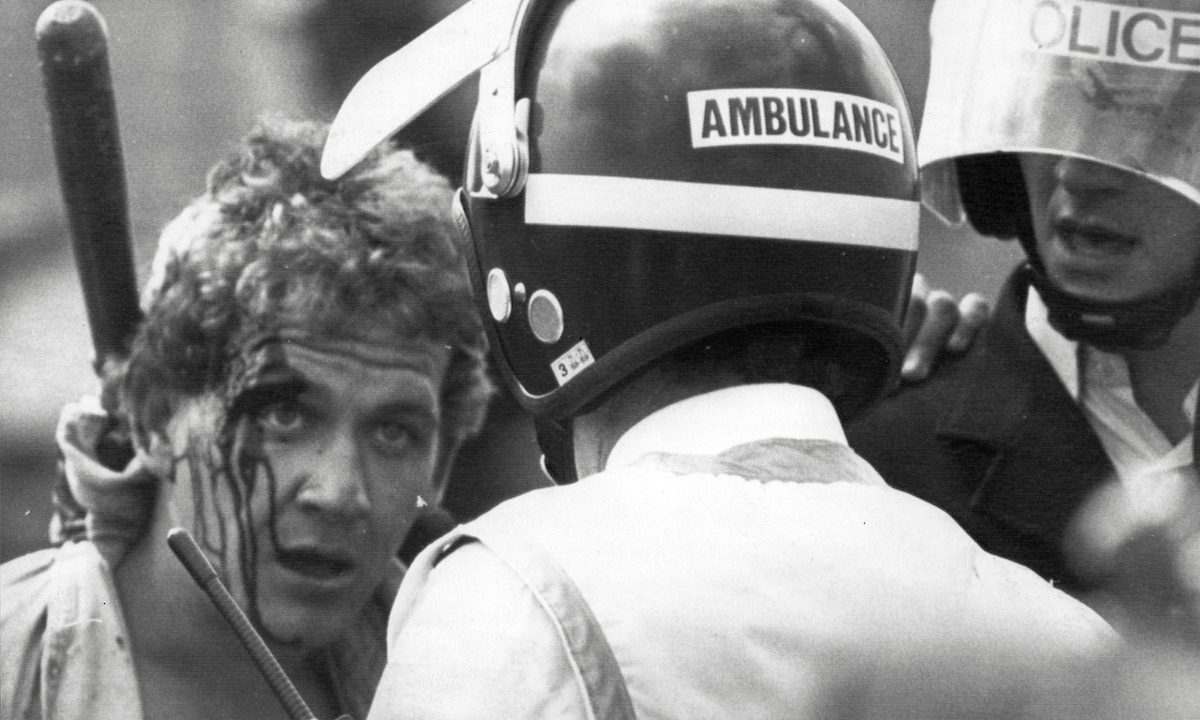

Police rode in on horseback and cracked miners on the heads. During the so-called “Battle of Orgreave,” the bloodiest of the crackdowns ordered by the Thatcher government, 6,000 riot police in full gear descended upon thousands of strikers. “Only people that rioted that day were police,” one eyewitness recalled. “They went berserk.” Another remembers, “anybody that happened to be in the vicinity was fair game… whether you were hit by truncheons or trampled by a horse or bit by a dog.” 95 miners were arrested and charged with rioting, a possible life sentence.

Then the strike was over, a year after it began, and the NUM miners returned to work with no concessions. The strike “changed Britain for ever,” Macintyre writes, breaking union power and opening the gates for neoliberal privatization policies that have reached their natural conclusion with today’s handful of billionaires who own most every industry. The police, Owen Jones argues in The Guardian, “were politicized, transformed into blunt instruments as part of a wider concerted mission to neutralize the British labour movement….”

As police forces in the U.S. have demonstrated on video for the last several years, the police in South Yorkshire in the 1980s “behaved as they did because they believed they had official sanction to do so. They then learned a lesson—quite reasonably—that they could act with impunity.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.