For several centuries, Westerners cast their eye to the Ottoman Empire for inspiration, especially after a 1580 commercial pact signed between Elizabeth I and Sultan Murad III brought about a period of “unprecedented contact” between cultures. “Alongside trade in lucrative commodities,” writes Dr. William Kenyan-Wilson, “many Europeans developed a deep fascination with Turkish art and architecture, religious culture and societal organisation.”

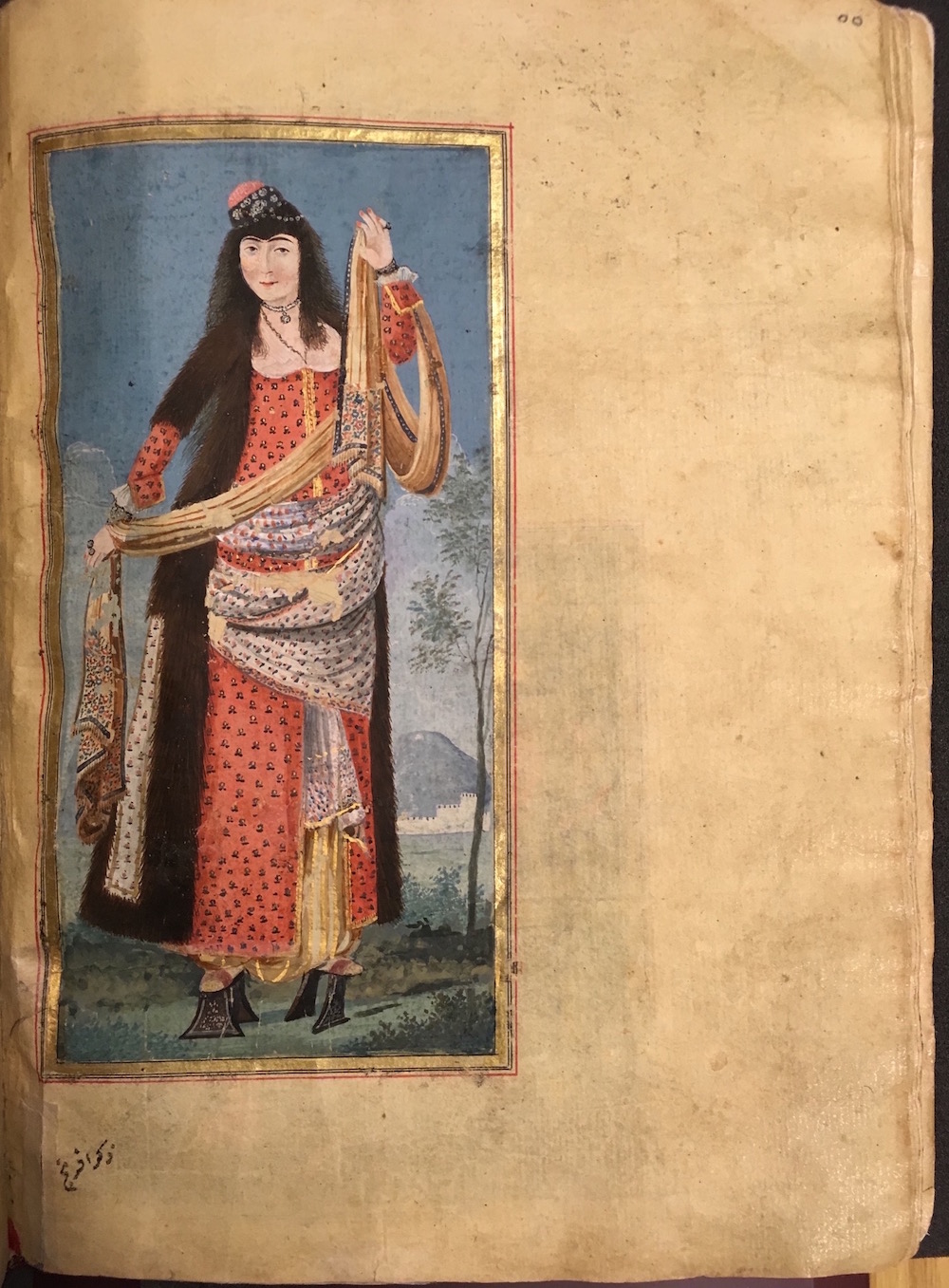

Europe’s buyers found their curiosity about the seductively- and sinisterly-construed “Turk” satisfied by so-called “Ottoman costume albums,” in which the Sultan, his court, ladies of various stations as well as ordinary Turks were painted in single-figure compositions in large folios. These were collected by merchants and Orientalists the continent over, into the early 20th century when photographic souvenir books took over for hand illustrated costume albums.

The gaze, of course, went both ways. For hundreds of years, both Ottomans and Europeans saw each other through the pages of these costume albums. Ottoman society was full of poets and artists who looked to the edges of their empire for subjects of their portraiture. They found a diversity of ethnic, national, and religious types collected in works like the illustrated Zenanname, or the “Book of Women,” a work from 1793 by the Ottoman Turkish poet Enderunlu Fazil. Boston University professor Sunil Sharma describes the text’s 38 illustrations, almost all of which are single-figure paintings:

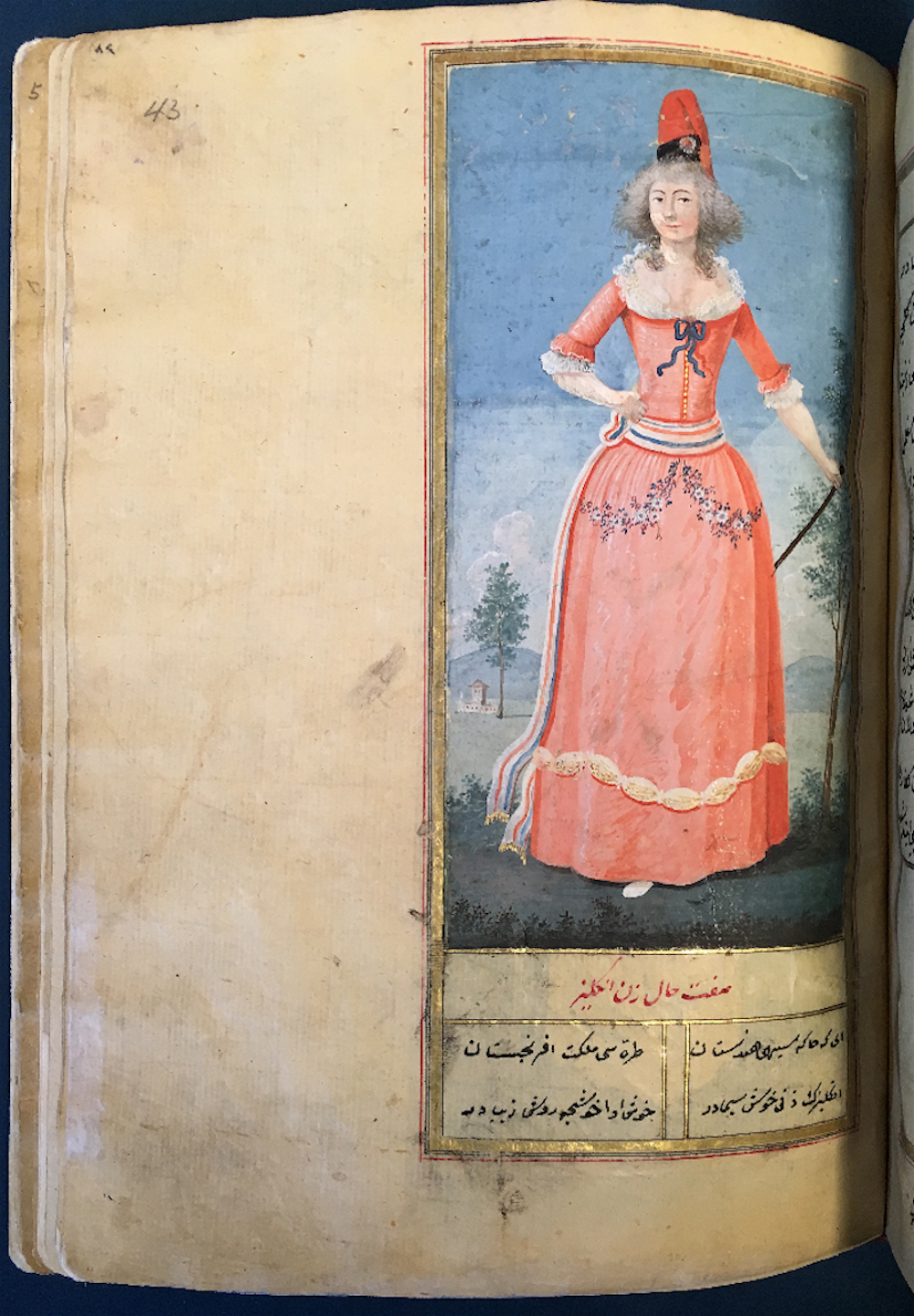

The women in the Zenanname represent every type known to the Ottomans from their empire and beyond. The paintings show women who are from a particular place or part of a community, comprising Indian, Persian, Baghdad, Sudan, Abyssinia, Yemen, Maghrib, Tunisian, Hijaz, Damascus, Syrian, Anatolian, the Aegean Islands, Spanish, Istanbul/Constantinople, Greek Christian, Armenian, Jewish, Gypsy, Albanian, Bosnian, Tatar, Georgian, Circassian, Christian, German, Russian, French, English, Dutch and American (from the New World).

Most European buyers considered “costume albums” to be worth little as art objects, writes scholar Gwendolyn Collaço. Such books were treated as exotic guides that reduced cultural differences to peculiarities of costume and complexion. (Their reception might help explain why, in 1910, a young Virginia Woolf and friends could board the HMS Dreadnought in turbans, robes, and blackface and convince the Caption and crew they were Abyssinian ‘princes.’)

In Istanbul, on the other hand, “local Ottomans granted bazaar paintings a much warmer response.” Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, Ottoman Turkish collectors, as well as those in Safavid Iran and Mughal India, treasured these books as early forms of “conspicuous consumption” among metropolitan elites.

Illustrated editions of the Zenanname seem to conform to the costume album genre, but instead of providing central focus, the images are secondary to Fazil’s poem. Readers are hardly encouraged to form their own interpretations of almost 40 ladies of the world depicted in the book. “Not all of these women are praised by Fazil,” Sharma points out. “Some are lampooned for their sexual behavior or nature in misogynistic terms.”

Fazil’s poem seems to celebrate the Englishwoman above all, at least on the surface. She appears in an illustration wearing a tall pointed hat and carrying a basket of flowers (pictured above in a different edition from Iran). The poet uses a kind of imperial geography to turn parts of her body into India (“Hindustan”) and Continental Europe (“Frankistan”) — as translated by Ottoman literary scholar E.J.W. Gibb:

O thou, whose dusky mole is Hindustan,

Whose tresses are the realms of Frankistan!

The English woman is most sweet of face,

Sweet-voiced, sweet fashioned, and fulfilled of grace.

Her red cheek to the rose doth colour bring,

Her mouth doth teach the nightingale to sing.

They all are pure of spirit and heart;

And prone are they unto adornment’s art.

What all this pomp of splendor of array!

What all this pageantry their heads display!

Her hidden treasure’s talisman is broke,

Undone, or ever it receiveth stroke.

Sly ribaldry permeates Fazil’s verse. However, the text circulated among European collectors not only for some bawdy lines but for its suggestive illustrations.

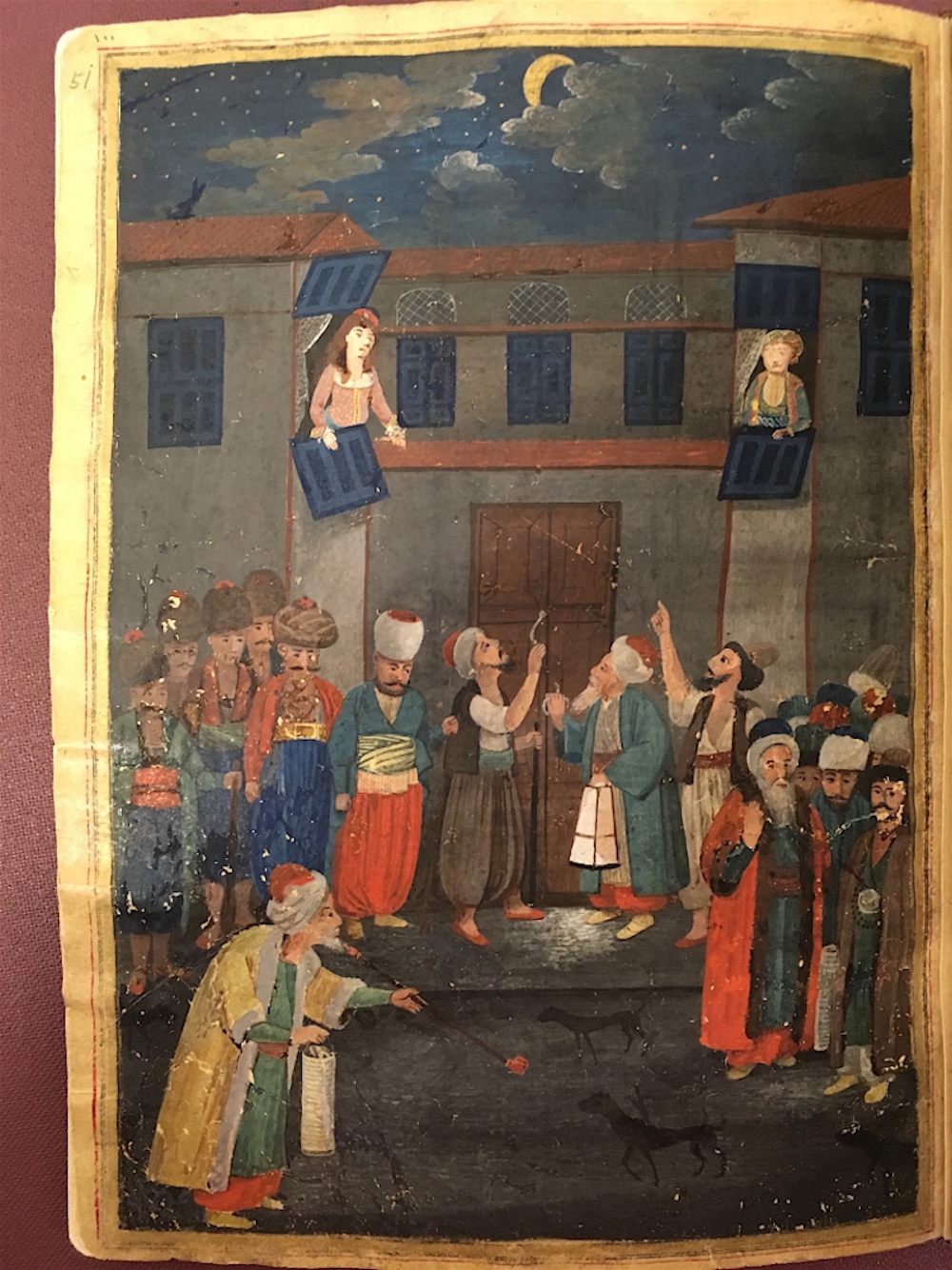

Two popular compositions in the Zananname show large groupings of figures. The first almost prefigures Seurat’s pointillist La Grand Jatte of nearly a century later, down to the stippled effect of its visible brush marks. Like the later Seurat, the painting depicts a bourgeois modernist vision, “showing people of different backgrounds and classes ‘mixing and mingling in the… gardens of the capital,'” writes Sharma.

A second image proves even more provocative — a group of men gathered in front of a brothel, an interesting scene compared to (male) European painters’ fascination with the Odalisque — the legendary Turkish concubine (or just as often, a hyper-sexualized Ottoman “white slave”).

The Zenanname uses the conventions of the costume album in its illustrated editions, but its verse comes from a different tradition, one that did not quite have an analogue in early modern European literature and art. This was the Persian shahrashub — books describing the most beautiful people in the city. In the hands of Ottoman poets — such as a writer known only as “Azizi” — the genre could became a catalogue of the famous prostitutes of Istanbul. But it was more usually — as in Fazil’s earlier companion work, the Hubanname, or “Book of Beauties” — verse descriptions of the prettiest dudes around.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.