One Toke Over The Line was performed on The Lawrence Welk Show, a television program known for its conservative, family-oriented format, by Gail Farrell and Dick Dale At the conclusion of the performance of the song, Welk remarked, without any hint of irony, “There you’ve heard a modern spiritual by Gail and Dale.”

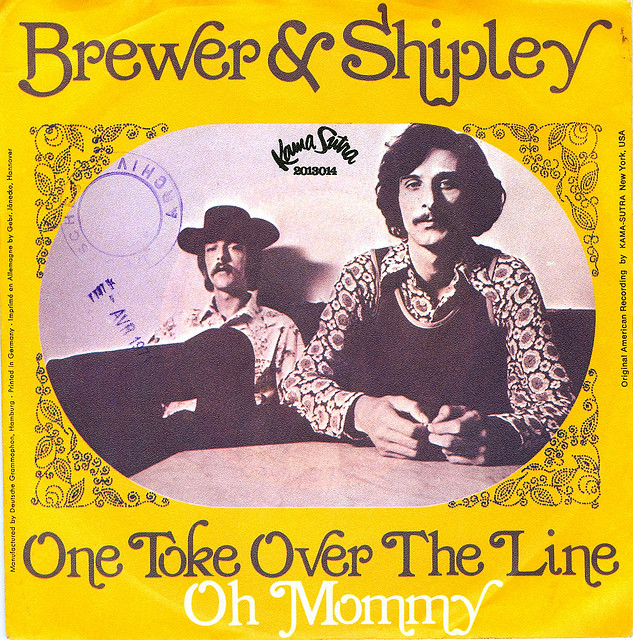

One Toke Over The Line was written in 1970 by Kansas duo Michael Brewer and Tom Shipley.

‘We were playing a little club in Kansas City,” Brewer told Rock Cellar magazine, “we had to do several sets a night and we were getting ready to go on for our last set. We stepped outside, shall I say, for a breath of fresh air. And we came back in and Tom said, “Man, I’m one toke over the line,” and it just cracked me up, I thought it was hysterical. Just right on the spot, I started singing, “One toke over the line, sweet Jesus” and then we went on stage. The next day we got together and we were sayin’, “What was that we were messin’ with last night?” In about an hour we had a song, just entertaining ourselves.

The president of their record company heard them play the song at Carnegie Hall. He urged them to record it as a single. The Lawrence Walk Show heard it and thought it just the thing to entertain the good folks turning in at home.

So when Brewer heard Welk’s comment, he was surprised on it being called a modern spiritual:

The Vice President of the United States, Spiro Agnew, named us personally as a subversive to American youth, but at exactly the same time Lawrence Welk performed the crazy thing and introduced it as a gospel song. That shows how absurd it really is. Of course, we got more publicity than we could have paid for.

He wasn’t kidding. In December 19709 The Illinois Crime Commission December held public hearings “on the narcotics and dangerous drugs problem.” It produced a list of “drug-oriented rock records,” and their meaning:

“Let’s Go Get Stoned” Joe Cocker: “lyrics have a double meaning , referring to alcohol but also to drugs.”

“A Whiter Shade Of Pale,” Procol Harum: “Mind-bending characteristics of the psychedelics.”

“Hi-De-Ho (That Sweet Old Sweet Roll),” Blood Sweat & Tears: “Joys of smoking marijuana.”

“With A Little Help From My Friends”: “Recorded by Sergio Mendes and Brash (sic) 66 on A&M Records … implying that those using narcotics, marijuana, or psychedelics share these drugs with one another.”

“White Rabbit,” Jefferson Airplane: “Extolling the kicks provided by LSD and other psychedelics.”

“Yellow Submarine,” Beatles: “Street jargon for yellow, barbiturate capsules.”

“Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds,” Beatles: “The initial letters in the title form the word LSD. The song depicts the pleasure of LSD.”

“Puff The Magic Dragon,” Peter Paul & Mary: “Smoking marijuana and hashish.”

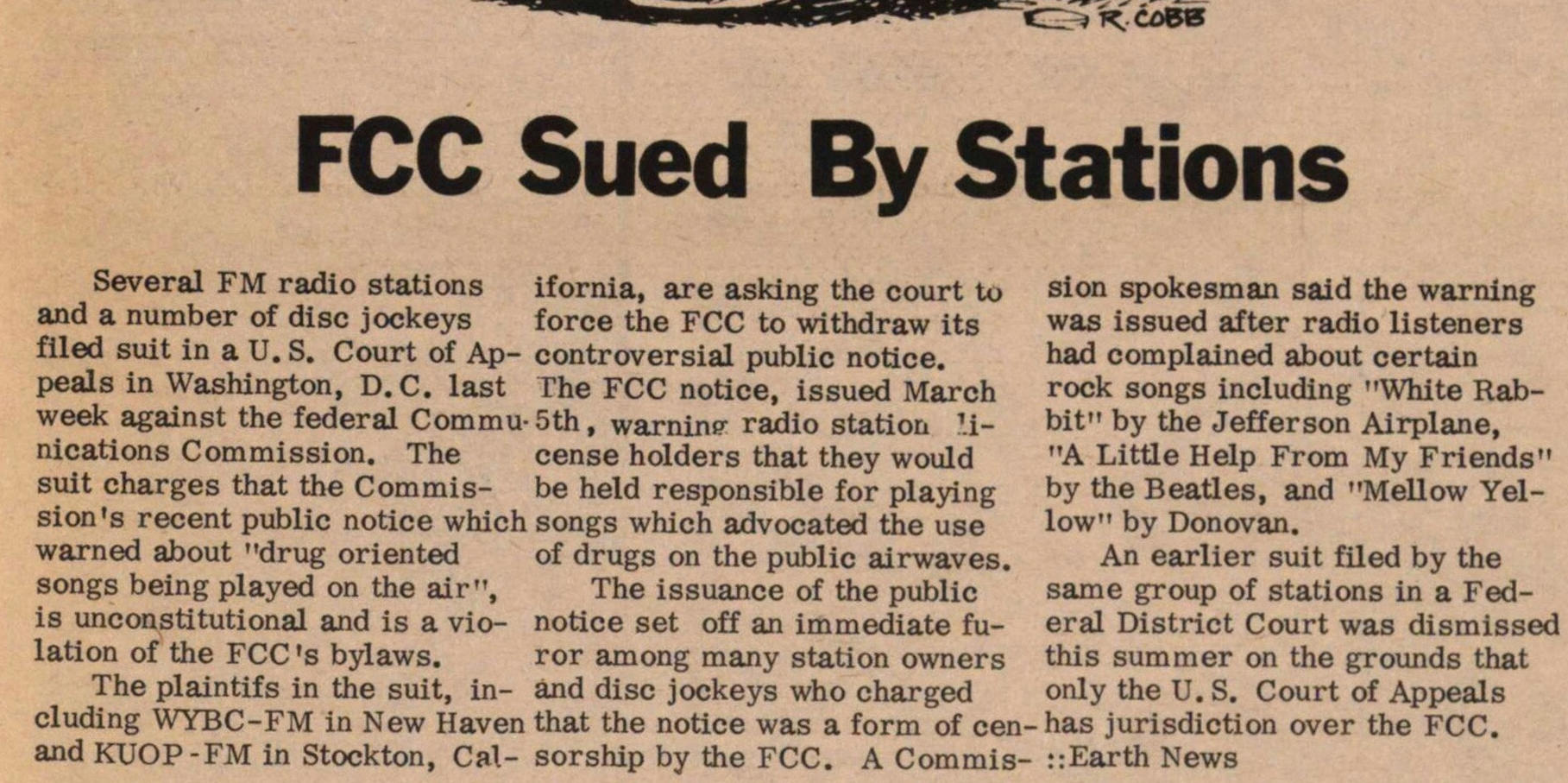

On March 5 1971, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ordered US broadcasters to stop broadcasting songs and spoken selections whose lyrics tend “to promote or glorify the use of illegal drugs”. Fail to comply the the censors and broadcasters would lost their licenses.

The FCC’s ruling went as follows:

“Whether a particular record depicts the danger of drug abuse, or, to the contrary, promotes such illegal drug usage is a question for the judgment of the licensee. The thrust of this notice is simply that the licensee must make that judgment and cannot properly follow a policy of playing such records without someone in a responsible position (i.e., a management level executive at the station) knowing the contents of the lyrics. Such a pattern of operation is clearly a violation of the basic principle of the licensee’s responsibility for … the broadcast material presented over his station. It raises serious questions as to whether continued operation of the station is in the public interest. In short, we expect licensees to ascertain, before broadcast, the words or lyrics of recorded musical or spoken selections played on their stations.”

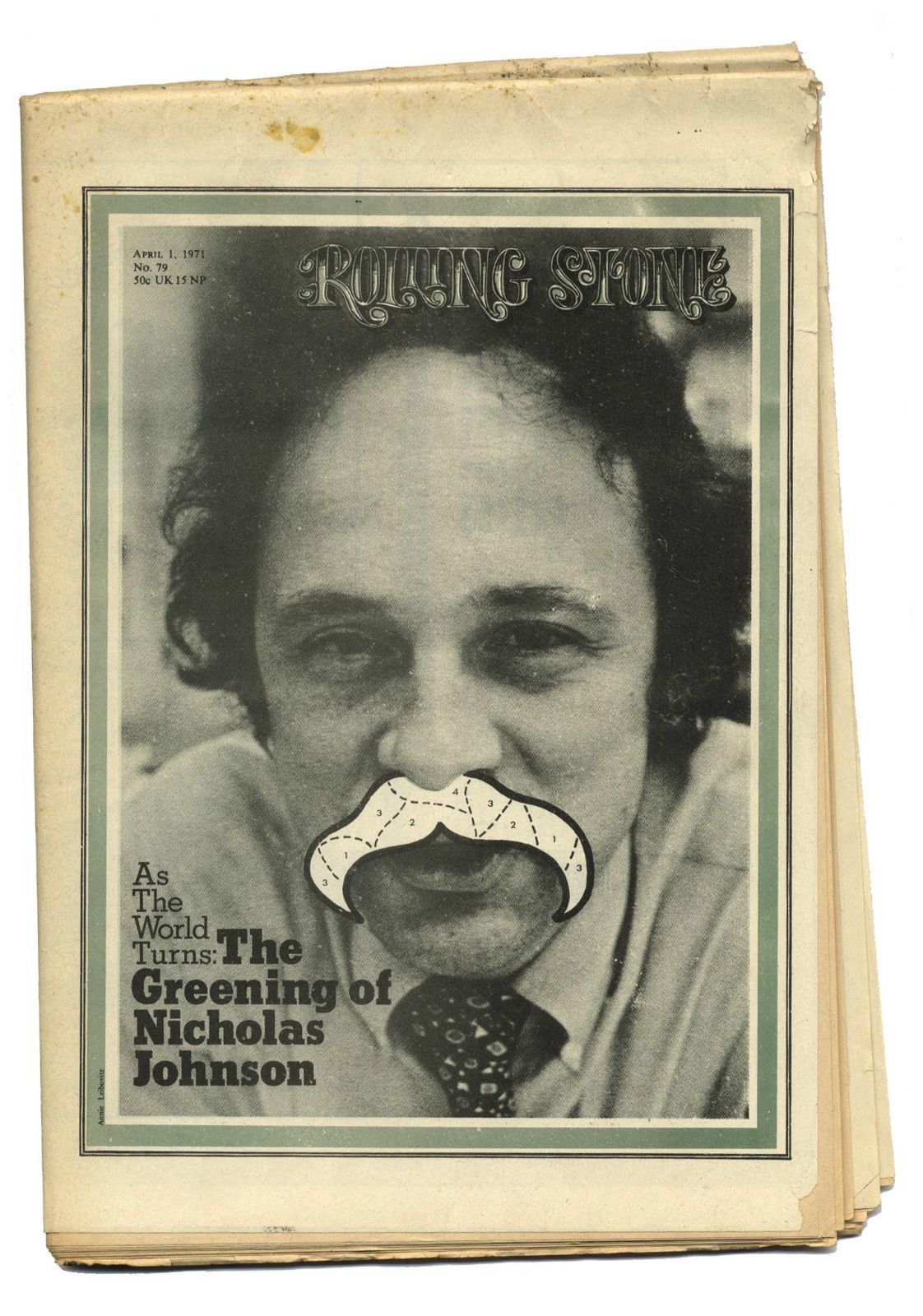

Nicholas Johnson on the Cover of Rolling Stone – April 1 1971. Via

Only one man on the six-strong FCC panel dissented. Nicholas Johnson called the ruling “an unconstitutional action by a Federal agency aimed clearly at controlling the content of speech… If the FCC is going to be used by the administration to frighten broadcasters to carry only stuff favorable to it, this country is in a lot more danger than any of us has imagined.”

Could anyone be certain what song was promoting drugs if the words were, as Agnew said, “coded”? Johnson spoke with San Francisco’s KSan-FM:

“The thing I find most ominous is that the presentation we received was put together by the Pentagon for the President, and this Defense Department briefing on song lyrics in fact used a lot of of lyrics that aren’t talking about drugs at all—they’re anti-war songs or songs attacking the commercial standards of society, the standards of conspicuous consumption.

“That raises some questions about what’s going on here. If the FCC is going to be used by the Administration to frighten broadcasters to carry only stuff favorable to it, this country is in a lot more danger than any of us has imagined.”

Broadcasters were unimpressed. Mel A. Phillips, program director for WRKO, said: “It’s censorship. I don’t think it’s fair at all… If you’re running a radio station and face loss of license or a $5000 fine. I could see where many radio stations would be selective. They might make an example of two or three key stations. But knowing the FCC, this could happen five years from now.”

On April 15, 1971, Ben Fong-Torres reviewed One Toke Over The Line for Rolling Stone magazine.

The first major casualty is a good example of the mentalities set loose by the FCC: “One Toke Over The Line,” a single by Brewer & Shipley that had been cleared by the trades and programming tipsters, and began a steady cruise up the charts – until the FCC issued it’s “reminder” (FCC’s word) to broadcasters to know the meaning songs that “tend to glorify or promote the use of illegal drugs such as marijuana, LSD, speed, etc.” again, the FCC’s wording. Now, at least half a dozen Top 40 stations have dropped the single because of the word “toke”.

“I frankly didn’t know what ‘toke’ was,” said Jeff Kaye program director of WKBW, in Buffalo. “So we did a street survey, and 90 percent of the kids said it had to do with marijuana.” So Kaye dropped the song…

Best call Bogart about those hidden drugs references.

“One Toke” is on Buddah Records, and Neil Bogart, president of the label, sounded pained as he rolled off the list of stations banning his record: KFJZ in Fort Worth (“where it was number six”); KLIF in Dallas (“number 18”); WFUN in Miami and WKBW in Buffalo; (In Chicago, WCFL matched Jeff Kaye by pulling “Itchycoo Park” by the Small Faces in addition to “One Toke.” They heard that “Itchycoo” is the name of a London hangout for smack addicts.)

So toking was out. (Incidentally, after Buddha Records, Bogart set up Casablanca Records in 1973. He signed Parliament, The Village People, KISS and Donna Summer.)

“I frankly didn’t know what ‘toke’ was,” admitted Jeff Kaye, the program director of Buffalo’s WKBW. “So we did a street survey, and 90 percent of the kids said it had to do with marijuana.” Kaye decided to purge his station’s playlist of that song and others that he deemed “beyond the boundaries of good taste,” including the Jefferson Airplane‘s “White Rabbit,” Bloodrock‘s “D.O.A.,” the Rolling Stones‘ “Monkey Man” and the Byrds‘ “Eight Miles High.”

Denied a hit, Tom Shipley, responded:

In this electronic age, pulling a record because of its lyrics is like the burning of books in the Thirties… You know people are always going to be reading whatever they want into a song whether it’s there or not…. One day we were pretty much stoned and all and Tom says, “Man, I’m one toke over the line tonight.” I liked the way that sounded and so I wrote a song around it.

It was a “cannabis spiritual”.

“That one silly song we wrote to kill some time between sets went over like gangbusters from the first time we played it live,” says Brewer. “Who would have guessed that it would end up being a classic rock song still played all around the world, in movies and stuff. It cracks me up. ‘Cause we were just kidding, we were just entertaining ourselves. Other people chose to make a big deal out of it. We were really happy just to get a hit, even if it wasn’t necessarily the one we would have picked,” said Brewer. “We’re really glad people still like it.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.