THE AMC original TV series Mad Men (2007 – ) set its latest season against a disquieting historical backdrop: the turbulent events of the year 1968.

Specifically, Matthew Weiner’s award-winning period drama book-ended the season with allusions to two classic genre films from that year: Franklin Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes and Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby.

Both are excellent selections that showcase, respectively, global and spiritual apocalypse.

Yet there is another film — one released on October 1st, 1968 — that also represents perfectly the turmoil of America during that season: George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead.

Today — due in large part to another AMC series, The Walking Dead (2010 – ), which is now airing the final portion of its fourth season — the zombie is arguably more popular a monster than ever before in genre history. Since Night of the Living Dead is its acknowledged spiritual and historical antecedent, the original film is thus eminently worthy of a re-watch in 2014.

Later sequel-ized in Dawn of the Dead (1979), Day of the Dead (1985), Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2007) and Survival of the Dead (2009) Romero’s low-budget, independently-produced Night has frequently been judged a metaphor for American involvement in the Vietnam War.

The film’s living dead, having risen from their graves, are frequently said to symbolize the soldiers killed in Vietnam as they return to haunt America’s guilty national conscience. The film’s staggering, vacant zombies have also been likened on occasion to the country’s “Silent Majority,” who went about their way, mindless and trance-like, as blood was spilled in Vietnam in their names.

Although such interpretations remain intriguing and valuable, Night of the Living Dead seems like much more than a commentary on an unpopular war. In fact, today the film plays as a nearly perfect time capsule for the agony and unrest – both foreign and domestic – of ’68.

In brief, this was a twelve month period in which it seemed that the average American was being overwhelmed and besieged by crisis and catastrophe. Not only did the Viet Cong storm the American Embassy during the Tet Offensive, but there were riots in more than a hundred American cities following the murder of Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4.

Just two short months later, Robert Kennedy was assassinated.

Beyond those tragedies, the violence and divisions stressing out America continued and deepened throughout the year.

For instance, in Chicago from August 22nd to August 30th anti-war protesters at the Democratic National Convention clashed with the Chicago Police Department and members of the Illinois National Guard. Ten thousand demonstrators were met with mace spray and truncheons by a combined force of approximately twenty-three thousand policemen and guardsmen.

Simultaneously, images of two these “armies” clashing in city streets were broadcast on every TV set in the nation.

One side in this battle wore traditional uniforms, and other side was dressed…very much like the home viewing audience itself.

So who were the good guys?

The violence outside the convention bled into the arena too, and CBS newsman Dan Rather was assaulted by “security” men while attempting to interview a delegate.

Anchor Walter Cronkite’s now-famous response to that act of violence?

“I think we’ve got a bunch of thugs here.”

Yep, they were “…all messed up,” to speak in the lingo of Night of the Living Dead.

A product either of lucky timing or a canny sub-conscious recognition of the prevailing national Zeitgeist, Night of the Living Dead captures in shocking and upsetting visual and thematic detail the notion of being overwhelmed; of the standing order collapsing before a marauding mass of people who look just like you do, but are heedlessly violent, irrational, and unstoppable.

I should probably note right here that Night of the Living Dead never adopts a political stance yay or nay on issues of Civil Rights or the Vietnam War, but rather that it trenchantly translates the imagery of the Chicago violence and other 1968 events to its horror scenario.

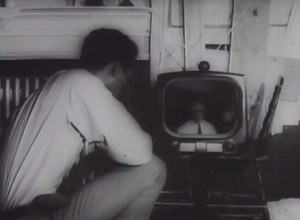

Specifically, the film expresses both the spiraling confusion of a battle between seemingly normal-appearing Americans with established authority, and the crucial act of watching the horror overwhelm society on television.

The chaos visualized in Night of the Living Dead seems only to multiply because so-called authorities can’t – or won’t – distinguish between people who might be “ghouls” and people who are but average citizens. So much like the violence marring America at the time, the Romero film is really about a Neo Civil War, a battle between the new social order which appears incomprehensible, frightening — and again, overwhelming — and the old social order, which appears corrupt in its response to that threat.

Night of the Living Dead’s depiction of rival social orders, and the ultimate re-assertion of the old order (so that everything stays the same…) is also projected in the film’s decorum-shattering, graphic imagery.

“This is no Sunday school picnic…”

Night of the Living Dead is based on Romero’s unpublished story called “Anubis.” In the narrative’s inaugural scene, a zombie is pursued and exterminated by armed human soldiers while fleeing over a hilltop.

Then, during tale’s the last shocking scene, another solitary figure flees across that same hill.

But the social order has now flipped.

The pursuer is now the pursued.

“We see it’s an army of zombies, chasing a human with an injured, bleeding leg,” Romero described in The Zombies That Ate Pittsburgh, (Paul R. Gagne, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1987, page 24).

“Anubis” was an allegory, Romero suggested, about shifting social orders. It concerned how there was this massive change, this massive revolution. Yet in some very important ways, things remained absolutely the same after the revolution.

That is precisely the ethos that dominates Night of the Living Dead, and also a good way of describing how history went after 1968.

Ultimately, after the counter-culture revolution, it was back to business as usual.

As every horror aficionado remembers, Night of the Living Dead concerns several disparate individuals who, during the early stages of a zombie apocalypse, seek refuge in an isolated farmhouse.

These survivors include the heroic, African-American man, Ben (Duane Jones), the shell-shocked, near catatonic Barbra (Judith O’Dea), the argumentative white man, Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman) and two teenagers — Tom (Keith Wayne) and Judy (Judith Ridley) — trying to make the best of a rotten situation. In the basement, Cooper’s wife, Helen (Marilyn Eastman) tends to her infected daughter, Karen (Kyra Schon).

These survivors argue about the best way to survive during the burgeoning national crisis, and huddle about a small TV set for “news” updates. Instead of proving comforting or helpful, the news reports only sow panic and more confusion.

At one point, the new-station cuts to footage of roving law-enforcement officials, who describe how to most efficiently kill the ghouls. A shot to the head is the key to destroying the enemy. The brain must be destroyed.

With the zombies laying siege to the farmhouse, only a few of the characters survive the night, and the film’s protagonist, Ben, dies from a shot to the head. His murderer is a member of an official (and lily white…) posse that travels the countryside killing the ghouls and “rescuing” the endangered citizenry.

Ben’s body is then burned on a pyre alongside ghoul corpses, with no acknowledgment that a living man, an American citizen, was murdered…

“We may not enjoy living together, but dying together isn’t going to solve anything.”

It is not difficult today to contextualize the ghouls in Night of the Living Dead as a force analogous to the convention protesters or other rioters of 1968, one bringing disorder and lawlessness to the streets of America. The ghouls- — like the protesters — look like us, but, at least at first, appear to behave in an inexplicable fashion. It’s difficult to know if they are friends and family members, or foes.

What do they want? What’s wrong with them?

As one of the characters notes in Night of the Living Dead, and quite apropos to the Chicago riot: “It’s difficult to believe something like this is happening.”

But Night of the Living Dead is never one-sided, or obvious. Instead, Romero recreates the entire milieu of the Chicago and other street riots because his film also depicts authority figures as confused and heavy-handed in their response to the breakdown of law and order.

They shoot first and ask questions later, and evidence no regrets about the finality of their approach. This is the very definition of Walter Cronkite’s so-called thuggery: roving bands of men armed with guns, killing those that they decree — on sight — to be enemies.

What Romero’s film seems to pointedly convey then is the very paradigm that was roiling in the pop culture at the time: that a significant change in the social order was indeed occurring, and occurring in a fast, unruly, even violent fashion.

Consider Bob Dylan’’s 1964 song, “The Times They Are A-Changing,” whose lyrics warned Senators and Congressmen that a “battle” was coming, one that would “shake the windows” and “rattle walls.” This idea of “the times”“a-changing” is deeply rooted in the situations and even dialogue of Night of the Living Dead. There are moments in the film where, indeed, the ghouls rattle the walls and shake the windows of that white farmhouse.

The idea of a change coming so fast that it overwhelms people is characterized in the very nature of the film’s central threat. The beleaguered heroes never have time to adjust to the new rules of survival, because of the overwhelming nature of the new enemy, the ghouls.

For example, early in the film, a ghoul slowly trudges into the farmhouse to menace Barbra, who, because of her PTSD, is unaware of its presence. Meanwhile, Ben fights two more ghouls right outside the door. He spots the ghoul threatening Barbra, and returns to kill it. But when he turns around after dispatching that threat, there’s another ghoul standing at the door.

And there are two more standing behind that one.

It is not that the zombies are fast or strong, it is that they keep coming, one after the other, and there is no end in sight. Life becomes a game of catch-up, trying to put out each little fire before another starts raging.

Those who saw TV reports of the Tet Offensive, the King and Kennedy assassinations, and the so-called “police riot” at the Chicago Convention might have felt in 1968 the same way as the film’s besieged heroes.

The danger and tragedy just kept coming, and all the old precepts about a “law and order” society were jeopardized.

This context of fast-moving change is reflected in another way too. Night of the Living Dead opens with a brother and sister, Johnny and Barbra visiting the grave of their deceased father. Their plan is to lay a wreath on the site, but this plan is disrupted by the presence of a ghoul in the cemetery.

At least metaphorically this scene concerns the idea of the young generation showing respect for the older generation. The cemetery, not coincidentally, is prominently decorated with American flags, suggesting that war veterans are interred there.

But even that simple idea of respect for the older generation’s national service can’t be taken for granted in the counter-culture age. Johnny complains about visiting the grave, and Barbara chides him for his cynicism, and, specifically, for missing church. “I haven’t seen you in church lately,” she notes.

Johnny replies that he doesn’t go to church anymore because there isn’t any point to his attendance. The implication is that he lives a life outside one that the Establishment of 1968 would consider virtuous or right. The old answers aren’t working anymore.

Even the setting of Night of the Living Dead suggests a violent changing of the guard, or the changing of the times. Johnny and Barbara arrive at the cemetery on a Sunday night, at the end of Daylight Savings Time, or “the first [Sunday] after the change to autumn,” writes R.H.W. Dillard in Night of the Living Dead: It’s Not Like Just a Wind That’s Passing Through” (Gregory Waller, Ed., American Horrors, University of Illinois, 1987, page 17).

Dillard observes that “The season, with its overtones of dying away and approaching winter cold, is symbolically significant, as is the Sunday, which emphasizes the failure of religion in the secular age.”

Other moments in the film also suggest the 1968 generation gap or hippie/establishment divide. Karen — a ghoul — kills her mother because her mother won’t defend herself. Helen doesn’t understand the new order, that it is a kill or be killed world now, and that humans are but food for the ascending dead. Sibling also turns against sibling, vis-à-vis Johnny and Barbra

Once more, the notion is of the old social order falling away, and a new one attempting to replace it.

A viewer can also see how this idea plays out in the film’s racial struggle. Ben is resourceful, quick-thinking and protective of his peers. He becomes — though constantly challenged by Cooper — the (effective) leader of his group. But then the old order represented by the white, heavily armed posse dismisses him out-of-hand as part of the unruly new order (the zombie threat) based on his physical appearance, and kills him without a second thought. The upshot is that a heroic, intelligent black leader dies. So nothing changes. The old order (of racism) persists.

The times, they were a-changing…or were they?

The zombies or ghouls in Night of the Living Dead represent the appearance of change, but it is the old order that wins the day (at least until Dawn of the Dead…), re-asserting its authority in the film’s final moments. This notion is suggested by the film’s spiky visuals as well. Night of the Living Dead features cannibalism, long a taboo in mainstream films, and showcases the graphic demise of its heroes. It’s very content is thus a “threat” or challenge to long-standing Hollywood convention. But importantly, the rebellion — the night of the living dead itself — is put down.

Today, it is easy to gaze at separate elements of Night of the Living Dead and assess them as commentary on individual issues reflecting the Vietnam War, or the Civil Rights movement. In the final analysis, however, the film offers instead what one might term the unified theory of the chaotic year 1968.

The times were changing, the social order was threatened, and the old guard was fighting back with a vengeance. If 1968 has an epitaph it should be, perhaps, in the words of Night of the Living Dead, that it was…”all messed up.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.