Trying to write a definitive history of the Acid Tests, a series of multimedia happenings in 1965 and 1966, in which everyone in attendance was stoned on LSD, is like trying to organize an aquarium’s worth of electric eels into a nice neat row, sorted by length. You will never get the creatures to stop writhing, let alone straighten out, and if you touch them, well, they are electric eels.

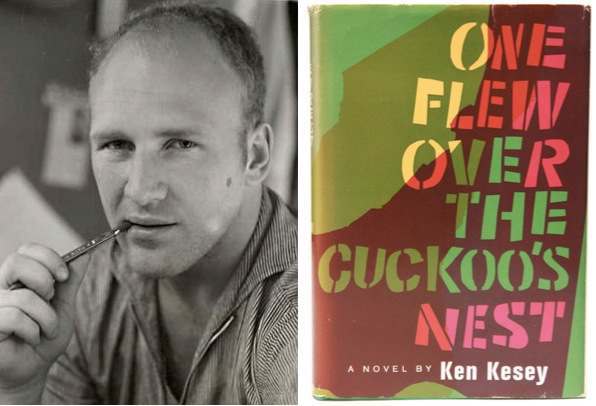

In 2015, key details from two of the earliest Acid Tests, which were funded and organized by One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest author Ken Kesey and his entourage, the Merry Pranksters, have become a preoccupation among certain music lovers. That’s because this year marks the 50th anniversary of the Grateful Dead, the house band for most of those drug-soaked bacchanals.

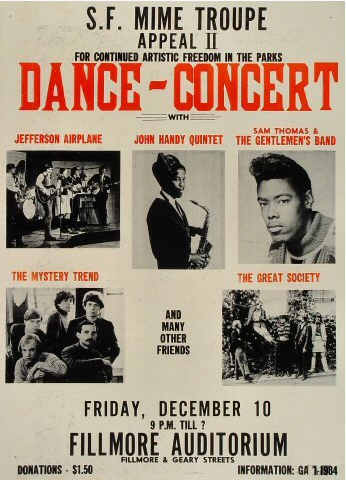

While music historians agree that the group’s first gig as the Warlocks was on May 5, 1965, at a pizzeria called Magoo’s in the San Francisco suburb of Menlo Park, there is less unanimity about when Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, Phil Lesh, and Bill Kreutzmann first took the stage as the Grateful Dead. Was it on December 4, 1965, at the San Jose Acid Test, the same night the Rolling Stones were performing a few blocks away? Was it on December 10 at the Fillmore Auditorium at a benefit for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, as stated by the band on its website? Or was it the very next night, December 11 (or, by some accounts, a week later on December 18), at the Muir Beach Acid Test, for which a poster exists bearing the band’s new name?

This is important stuff. After all, if scholars cannot agree upon a one true date, how will legions of Deadheads know when to post photographs of themselves in full tie-dye regalia on Facebook?

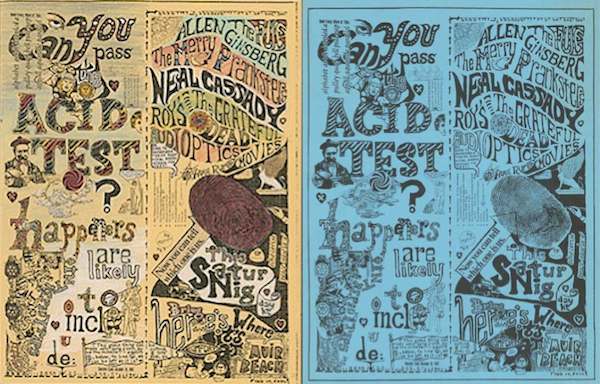

Above: Author Ken Kesey used some of the money he made from his 1962 novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, to fund the Acid Tests of 1965 and 1966. Top: The undated Muir Beach Acid Test poster by Paul Foster. The one on the left was hand-colored by Sunshine Kesey. Via dead.net.

Fortunately for Nicholas Meriwether, getting to the bottom of this weighty question is not his job. You’d think it might be, since Meriwether is the Grateful Dead archivist for the McHenry Library at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where the voluminous Grateful Dead Archive is housed. But when it comes to the Dead’s early years, Meriwether gets a pass. “The archive doesn’t really start until 1970,” he tells me over the phone, “because the band didn’t incorporate until that year. We’ve got a few things from before then, but precious little. Nothing would please me more,” he adds, “than to be able to say, ‘Come on down, and I’ll show you my Acid Test trove.’ Sadly, I don’t have one.”

In today’s culturally conservative climate, it’s difficult to imagine a university, even one with such esteemed counterculture bona fides as UC Santa Cruz, creating a public space to honor the overconsumption of psychedelic drugs. Still, it would probably surprise many millennials, and a lot of their parents, to learn that in 1965, LSD was legal with a prescription, usually from a psychiatrist. That meant LSD was widely available, as easy to get your hands on as, say, Oxycontin and other prescription drugs are today.

In fact, the Acid Tests were somewhat late to the psychedelic party. The CIA began experimenting with LSD in the early 1950s, dosing everyone from prisoners to prostitutes (usually without warning, let alone consent) to study the drug’s disorienting effects. That’s how Ken Kesey learned about the drug in 1959, when he signed up to be a test subject in the CIA’s notorious MKUltra program. Future Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter was also willingly dosed by the CIA.

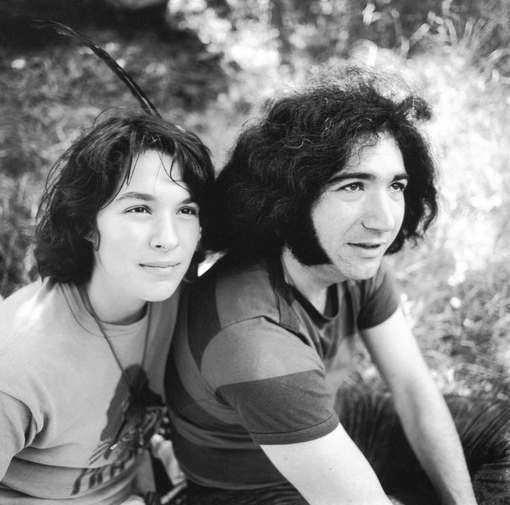

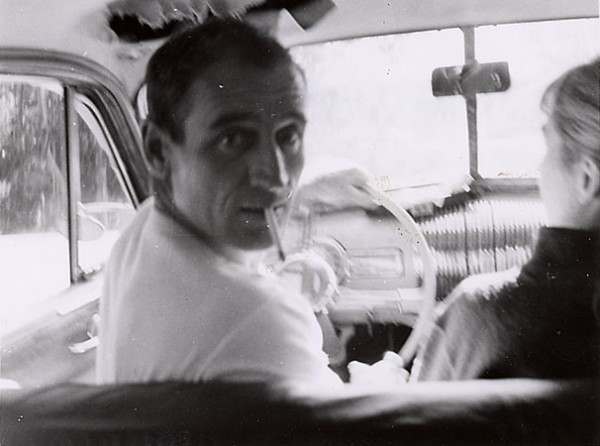

Neal Cassady, seen here in a photo by poet Allen Ginsberg, was the prototype for the hero in On the Road by Jack Kerouac. Both Cassady and Ginsberg were participants in the Acid Tests.

Corporate America, or at least some of those working in its dimly lit corners, also pondered the potential benefits of the drug. As journalist John Markoff recounts in his 2005 book, What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry, in the early 1960s, more than 350 Silicon Valley engineers paid a fellow engineer named Myron Stolaroff, of the International Foundation for Advanced Study, $500 apiece to be taken on an acid trip, so that they might use the experience to achieve breakthroughs on difficult technical problems, as well as to improve their overall creativity. Other guides such as psychologist James Fadiman took engineers like Doug Engelbart of the Stanford Research Institute on a pair of trips. Engelbart predicted our computer-connected world in 1968 when he gave what’s known as “The Mother of all Demos.” He’s also the guy who invented the mouse, but on his second guided acid trip, Markoff reports, Engelbart’s epiphany was a never-to-be-realized design for “a waterwheel that would float in a toilet bowl and spin when water (or urine) was run over it.” In other words, a toilet-training device for little boys.

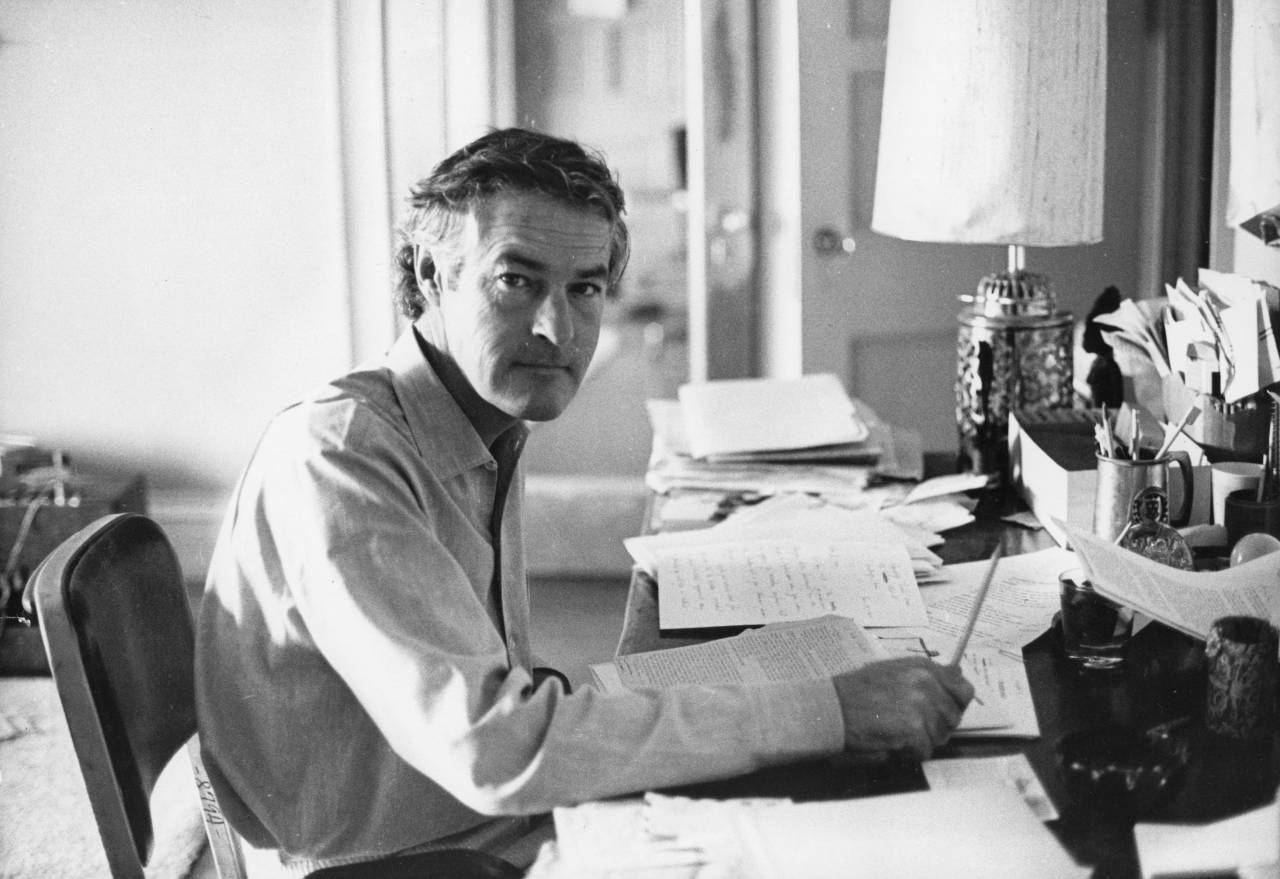

Dr Timothy Leary, the LSD advocate, working at his desk. Original Publication: People Disc – HG0050 (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

During the first half of the 1960s, LSD proselytizers like Storlaroff and Fadiman were probably still able to get their hands on doses of the drug that had been produced by its sole manufacturer, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals of Switzerland. After California made LSD and its psychedelic cousin, DMT, illegal onMay 27, 1966, enterprising amateur chemists such as Owsley Stanley filled the supply vacuum by synthesizing LSD in makeshift labs, producing millions of doses for the burgeoning black market. According to a Consumers Union report, “A million 250-microgram doses weigh about nine ounces,” which meant the odorless drug was easy to conceal and transport.

Which brings us back to the Acid Tests and the roots of the Grateful Dead brand. If the CIA was interested in how LSD could be used to control minds, and if advocates such as Storlaroff were hopeful the drug could make already dazzling minds even more brilliant, Kesey and the Merry Pranksters were more aligned with the “turn on, tune in, drop out” school of acid exegesis, as preached by former Harvard University lecturer Timothy Leary.

The Tests themselves, though, were a good deal more complicated than that. Although the Grateful Dead played music at these affairs (covers of 1965 hits like “Wooly Bully” by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs and “Do You Believe in Magic” by the Lovin’ Spoonful have been cited as part of the repertoire for the earliest Tests, but no definitive record survives), the music they played was usually competing with the electronic cacophony produced by the Pranksters, which included on-the-scene recording, tape loops, and lots of dissonant, often ear-splitting feedback.

Typically, the Pranksters would set up their audio gear on one side of wherever a Test was being held, while the Dead’s amplifiers and instruments, including Pigpen’s Hammond B-3 organ and Kreutzmann’s drum kit, would be arrayed on the other. Lights, including strobes, were an important part of the mix, illuminating, if only accidentally, Beat Generation hero Allen Ginsberg reciting his poetry or Neal Cassady, the prototype for the Dean Moriarty character in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, leaning into a microphone to deliver amphetamine-fueled, stream-of-consciousness raps. The presence of Ginsberg and Cassady at some of the earliest Acid Tests makes these events bridges between the Beats and the Hippies, but the Acid Tests are best remembered for dissolving the line between performers and audience. At an Acid Test, participation was the only rule, a no-spectators ethic that makes the participatory spectacle of Burning Man look about as spontaneous as a Super Bowl halftime show.

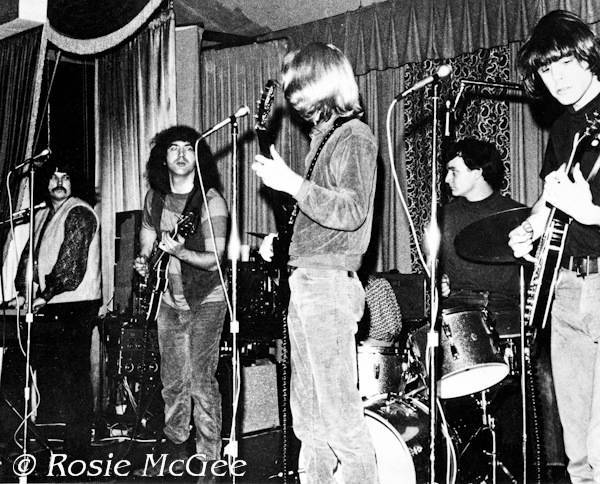

The Grateful Dead performing at Troupers Hall in Los Angeles on March 25, 1966. This show is often listed as an Acid Test, but it was not, according to photographer Rosie McGee. From left to right: Pigpen, Garcia, Lesh, Kreutzmann, and Weir.

All that participation was exhausting, as the Grateful Dead’s lead guitarist and main creative force, Jerry Garcia, and his then-girlfriend, Mountain Girl, née Carolyn Adams, discuss in Garcia: A Signpost to New Space. In that book-length pair of interviews, published in 1972, with then “Rolling Stone” publisher Jann Wenner and then Yale University law school professor Charles Reich, the two traded recollections on how they felt the following day:

MOUNTAIN GIRL: After an Acid Test was always morning. You start to pack up and step outside and it would be cold there and, ohhhh, really clear and everybody looking about eight inches shorter than they had been when they walked in, and about 20 pounds lighter. Not particularly haggard looking, but just a lot littler and packed down.

JERRY: Well used.

MOUNTAIN GIRL: And everybody would creep off home. Driving back was a really far-out experience because we always had to drive over this mountain route to La Honda. [Mountain Girl was living there with Ken Kesey during the early Acid Tests.]

JERRY: It always seemed really remarkable that…

MOUNTAIN GIRL: … that we were still alive.

JERRY: …That actually another day went by… there’s the sun again another day, God, isn’t it incredible it had been a long, long night.

For Garcia, the ability of the Acid Tests to stop the world for a while and then remind you that it was still spinning was one of its key lessons. The Acid Tests, he says in Signpost, were “our first exposure to formlessness. Formlessness and chaos lead to new forms. And new order. Closer to, probably, what the real order is. When you break down the old orders and the old forms and leave them broken and shattered, you suddenly find yourself a new space with new form and new order which are more like the way it is. More like the flow.”

To put Garcia’s formulation in terms a contemporary Silicon Valley venture capitalist might understand, LSD was a disruptive technology, except that instead of upending mere transactions such as hailing a cab or renting a hotel room, the things being disrupted were the basic conventions of society, which is why mainstream America was, and remains, so terrified of the drug.

In 1965, LSD was still legal in California, where the early Acid Tests took place. Image on left courtesy Farmer Dodds. Image on right courtesy the Herb Museum.

Indeed, as Garcia remembers it, “the form that we liked always scared everybody. It scared the people that owned the building that we’d rent, so they’d never rent twice to us. It scared the people who came, a lot of times. It scared the cops. It scared everybody. Because it represented total and utter anarchy.” As anarchic, you might say, as an aquarium full of writhing electric eels. Many people, like Garcia and Kesey, thrived on this self-imposed proximity to danger, getting off on the drug’s electric jolts, and gleefully jolting back. Others pretty much lost their minds.

Even for those who thrived on the experience of the Acid Tests, LSD colored their memories—to put it mildly—which is one of the main reasons why the origins of the Grateful Dead’s name are so squirrely. “I’m not trying to cop out on you by saying this,” Meriwether tells me, “but the thing you have to keep in mind is that LSD is the most powerful drug we’ve ever discovered. Its capacity to magnify the importance of certain things and make them stick in people’s memories is going to complicate any kind of recollection of a particular event.”

There’s an old adage that if you can remember the ’60s, you probably weren’t there. If you can remember the Acid Tests, then your recollections are perhaps even more suspect.

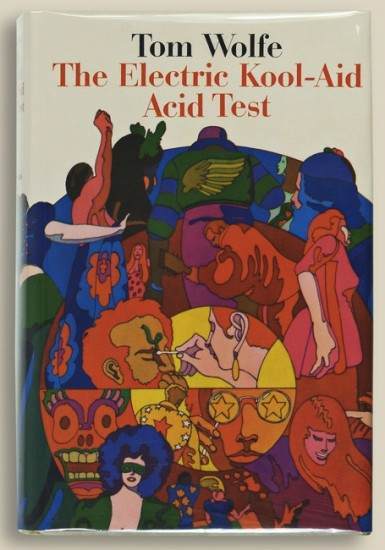

All of which may be why so many Grateful Dead and Acid Tests historians have come to rely on the accounts of novelist Tom Wolfe, whose The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test from 1968 includes brief, but vivid, pictures of the San Jose and Muir Beach Acid Tests, neither of which Wolfe attended.

According to Ken Kesey, Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, published in 1968, was 98 percent accurate.

“Kesey called Wolfe’s book 98 percent accurate,” Meriwether says, which is pretty good considering Wolfe wasn’t there. But Wolfe was a diligent journalist, which allowed him to piece together intimate descriptions of San Jose and Muir Beach, primarily via interviews with Ken Kesey. “Garcia said that he thought Ken Babbs of the Pranksters was more of a central driving force in the Acid Tests than Kesey,” Meriwether says, “but part of the Prankster line about The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test has always been that Tom Wolfe was a writer who found Kesey instinctively comprehensible, and whose story had a kind of magnetism that made him the logical protagonist of the book. Whether it felt that way to the people at the time is a bit more difficult to know.”

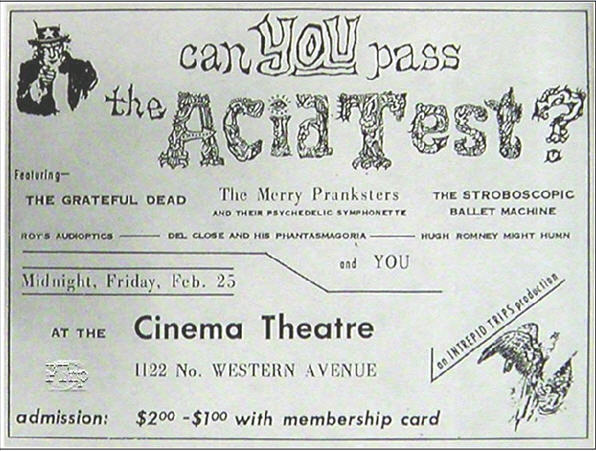

And what did Kesey tell Wolfe? Well, after the first Acid Test was held on November 27, 1965, at Ken Babbs’ place near Santa Cruz, Kesey and the Pranksters thought it would be a good idea to do a bigger bash closer to the multitudes. The Rolling Stones would be playing the following weekend in San Jose, so why not host one there? Kesey knew a guy in San Jose, a “local boho figure,” as Wolfe describes him, and whom Kesey called “Big Nig.” To 2015 ears, Big Nig seems an obviously racist nickname for a large African American male, but it’s not much worse than Wolfe’s “poor pathetic spade” in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Regardless, most Acid Test scholars give credence to Wolfe’s description of events:

“This very night,” Wolfe writes, “the Pranksters all sit down with oil pastel crayons and colored pens and at a wild rate start printing handbills on 8½ X 11 paper saying CAN YOU PASS THE ACID TEST? and giving Big Nig’s address. As the jellybean-cocked masses start pouring out of the Rolling Stones concert at the Civic Auditorium, the Pranksters charge in among them. Orange & silver Devil, wild man in a coat of buttons—Pranksters. Pranksters!—handing out the handbills with the challenge, like some sort of demons, warlocks verily, come to channel the wild pointless energy built up by the Rolling Stones inside.

“They come piling into Big Nig’s, and suddenly acid and the worldcraze were everywhere, the electric organ vibrating through every belly in the place, kids dancing not rock dances, not the frug and the—what?—swim, mother, but dancing ecstasy, leaping, dervishing, throwing their hands over their heads like Daddy Grace’s own stroked-out inner-courtiers—yes!—Roy Seburn’s lights washing past every head, Cassady rapping, Paul Foster handing people weird little things out of his Eccentric Bag, old whistles, tin crickets, burnt keys, spectral plastic handles. Everybody’s eyes turn on like lightbulbs, fuses blow, blackness—wowwww!—the things that shake and vibrate and funnel and freak out in this blackness—and then somebody slaps new fuses in and the old hulk of a house shudders back, the wiring writhing and fragmenting like molting snakes, the organs vibro-massage the belly again, fuses blow, minds scream, heads explode, neighbors call the cops, 200, 300, 400 people from out there drawn into The Movie, into the edge of the pudding at least, a mass closer and higher than any mass in history, it seems most surely, and Kesey makes minute adjustment, small toggle switch here, lubricated with Vaseline No. 634-3 diluted with carbon tetrachloride, and they ripple, Major, ripple, but with meaning, 400 of the attuned multitude headed toward the pudding, the first mass acid experience, the dawn of the Psychedelic, the Flower Generation and all the rest of it, and Big Nig wants the rent. ”

In contrast, Garcia remembers San Jose this way in Signpost: “It was in a house, right, after a Stones concert, the same night, the same night. We went there and played but, you know, shit, our equipment filled the room, damn near, and we were like really loud and people were just, ah… there were guys freakin’ out and stuff, and there were hundreds and hundreds of people all around, in this residential neighborhood, swarming out of this guy’s house.”

Wolfe’s account continues with a goofily stoned encounter between Garcia and Big Nig, who’s hitting up the guitarist for some scratch to help pay his bills. Money was actually an important element of the Acid Tests, although not for the purposes of gate-keeping. It was a symbol of the lack of distinction between performers and audience—everyone was supposed to participate equally.

“The Acid Test was a buck, but everybody paid it,” Garcia says in Signpost. “The musicians paid it, the electricians paid it, the guy that collected tickets paid it, everybody paid it, and if there was only one buck we’d all pay it over and over again. It was always an exchange, it cost you a buck and you stayed there all night.” Except at Big Nig’s, since San Jose’s finest broke up that Test in the early morning hours of December 5.

And who supplied the LSD at the December 4 Acid Test? “People are mighty skittish about ever, ever going into details like that,” Meriwether says. Imagine that.

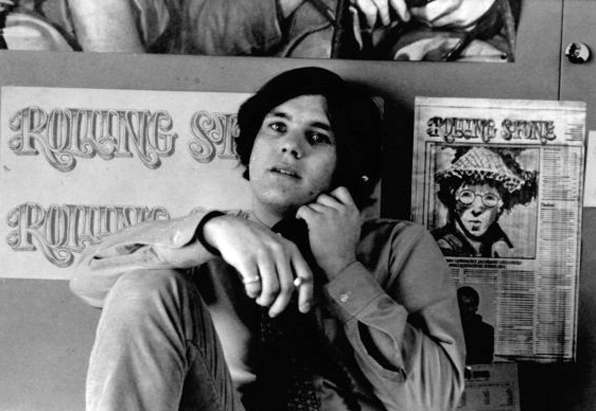

Future “Rolling Stone” publisher Jann Wenner attended the San Jose Acid Test. Photo by Baron Wolman via jannswenner.com.

As it turns out, unlike Wolfe, future “Rolling Stone” publisher Jann Wenner was actually at Big Nig’s in San Jose that night after the Rolling Stones concert. Not surprisingly given his future vocation, Wenner was a reporter for UC Berkeley’s “Daily Cal” at the time. As he recalls in his foreword to Signpost, “I wandered into a Kesey scene there that turned out to be the first Acid Test. I remember asking someone (who turned out to be Phil Lesh) who they were. ‘We’re the Grateful Dead,’ he said, and the impact, in my state of mind at that point, was severe.”

“First public Acid Test,” Wenner probably meant to write, since the first Test had actually been at Babbs’ place the previous week. In his defense, Wenner probably wasn’t overly focused on Acid Test chronology when he was writing his foreword in 1972—there’d be plenty of time one day in the future to get it all down for posterity, right?

What matters for our purposes is that Wenner, arguably the 20th century’s most important and influential rock journalist and publisher, got his scoop on the band’s name directly from the its bassist, Phil Lesh, who played an important role in giving the band its name—it was at Lesh’s home that Jerry Garcia came upon the phrase “The Grateful Dead” in “a big Oxford Dictionary,” as Garcia remembers it in Signpost. That may be why the name was so fresh in Lesh’s mind when he told Wenner “We’re the Grateful Dead.” But can a band have a name if there is no written record of it?

Given, though, the unimpeachability of these sources, December 4, 1965, appears to be the first time the Grateful Dead performed as the Grateful Dead, right?

Maybe. Part of the problem remains the inherent unreliability of Wenner’s “state of mind,” to use his coy phrase, or that of anyone else in attendance. But the larger issue may actually be the mercurial nature of the band’s name after its members decided to drop Warlocks as their moniker. As Garcia also recalls inSignpost, “We sort of became the Grateful Dead because we heard there was another band called Warlocks. We had about two or three months of no name and we were trying things out, different names, and nothing quite fit.”

Which two or three months Garcia is referring to is hard to say, but Meriwether has a suggestion. “Perhaps one thing that can help anchor the chronology,” he offers, “is the band’s demo in early November for Autumn Records, when they recorded as the Emergency Crew.” That would have been a very, very bad name for the band millions love as the Grateful Dead, but Meriwether says Deadheads might have been stuck with even worse—apparently Vanilla Plumbago and Mythical Ethical Icicle Tricycle were also briefly on the table.

The Grateful Dead performed at this concert, but their name is not on the poster, and a newspaper review of the show three days later refers to them as the Warlocks. Via jerrygarcia.com.

That takes us to the following weekend, December 10 and 11, when the band, whatever its name, performed two nights in a row, although it’s not totally clear where. The first gig was definitely at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, in a benefit for the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Neither the Warlocks or Grateful Dead are on the poster for that show, but a December 13, 1965, review in the “San Francisco Chronicle” by Ralph Gleason mentions the presence of a band called the Warlocks performing at the Fillmore on December 10. This is the same show that’s listed on the Grateful Dead’s own website as being the band’s “first show” as the Grateful Dead. Given the lack of official documentation, and Lesh’s words to Wenner the previous weekend, this claim does not appear to be true.

Unless it is. According to former Grateful Dead publicist and historian, Dennis McNally, Fillmore concert promoter Bill Graham booked the Warlocks for the December 10 benefit, but between the time of the booking and the show, they had changed their name to the Grateful Dead. Graham “loathed” the band’s new name, McNally says, so when he wrote the band’s name on a chalkboard that rested on an easel at the side of the stage, he added the words “formerly the Warlocks.” No photographic record of this signage exists, but McNally, who was not there, got his story directly from Graham, and McNally says Garcia and Lesh confirmed it.

The Muir Beach Lodge, circa 1948, site of an Acid Test on either December 11 or 18, 1965. Via bellobeach.com.

In Living with the Dead, former Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully, who was at the Fillmore show, with “acid king” Owsley Stanley, no less, doesn’t mention a chalkboard, but he does recall hearing an “emcee” in a “Don Pardo voice” introducing the band this way: “Formerly the Warlocks of Palo Alto, ladies and gentlemen, I give you the Grateful Dead.”

The next night, the band participated in a third Acid Test, but sources differ on exactly where it took place. Sticking with Wolfe’s 98-percent accurate chronology for a moment, it may have been held at an old lodge in Muir Beach, just north of the Golden Gate Bridge. And here, finally, we find evidence in the form of a poster by Paul Foster promising The Fugs, Allen Ginsberg, the Merry Pranksters, Neal Cassady, Roy’s Audioptics, Hugh Rumbly (a play on the name Hugh Romney, who is better known as Wavy Gravy), and, yes, the Grateful Dead, who… oh, let’s let Tom Wolfe pick up the story again, shall we?

“The Dead’s weird sound! Agony-in-ecstasis! Submarine somehow, turbid half the time, tremendously loud but like sitting under a waterfall, at the same time full of sort of ghoul-show vibrato sounds as if each string on their electric guitars is half a block long and twanging in a room full of natural gas, not to mention their great Hammond electric organ, which sounds like a movie house Wurlitzer, a diathermy machine, a Citizen’s Band radio and an Auto-Grind garbage truck at 4 A.M., all coming over the same frequency…”

The Big Beat, site of the third or fourth Acid Test, was still standing when Corry Arnold took this photo in 2009; it has since been torn down. Via Rock Prosopography 101.

For Meriwether, the impact of the Acid Tests on the band that was becoming the Grateful Dead was more profound than Wolfe’s winking references to electronic medical devices used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, or even his poetic, if still secondhand, descriptions of the band’s sound. “The Acid Tests,” Meriwether says, “taught them things about communication that cemented their desire to create an approach to improvisation that went far beyond traditional models. What the Dead learned and experienced at the Acid Tests was that everybody could solo simultaneously, and that it could work. That was the trait that made their music so absolutely mesmerizing throughout their 30-year career. They were already heading down that path, but the Acid Tests were the laboratory, the space for them to really see what was possible.”

“The Acid Test was the prototype for our whole basic trip,” Garcia tells Wenner in Signpost. “But nothing has ever come up to the level of the way the Acid Test was. It’s just never been equaled, really… The scene now is [like] watching television or going to a movie. That’s essentially what’s happening, you go into the show, there’s a proscenium arch, there’s the speakers, visually you’re focused right at the center of things, the sound is coming at you from that direction; there might as well not be any back of your head, there’s nothing happening back there and so it’s that same old experience, … the very flaw that we were trying to eliminate with that Acid Test. The Acid Test was going in a whole other direction, something completely weird.”

Mountain Girl’s Acid Test graduation diploma, via SF Rock Posters.

At this point, it must be noted that both the Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia websites list the third Acid Test on December 11 as occurring at a Palo Alto nightclub called the Big Beat. Similarly, in Living With the Dead, Rock Scully remembers Owsley Stanley driving him to the Big Beat in his Morris Minor the night after seeing the Grateful Dead, “formerly the Warlocks,” at the Fillmore. Other sources, though, from Tom Wolfe to—are you sitting down?—Owsley Stanley say Muir Beach occurred on December 11. For example, here’s Stanley talking to author Robert Greenfield in Dark Star: An Oral Biography of Jerry Garcia, “In December ’65, I really heard the Grateful Dead for the first time. It was at the Fillmore the night before the Muir Beach Acid Test.” Since everyone agrees that the Dead only played the Fillmore once in December of 1965, on the 10th, that appears to corroborate an Acid Test on the 11th, probably somewhere in northern California.

Then again, in the late 1960s, Stanley is thought to have manufactured a million hits or more of LSD, and Scully says that the night he saw the Dead/Warlocks at the Fillmore, he had consumed “a couple hundred mikes” of Stanley’s best stuff. These gentlemen, both no longer with us, are what an attorney would call “unreliable witnesses.”

Whatever. I’m going with this: First verbally confirmed performance as the Grateful Dead for which there is no physical evidence: the Acid Test at Big Nig’s in San Jose, December 4. First chalkboard-credited, verbally announced performance as the Grateful Dead for which there is also no physical evidence: Mime Troupe Benefit at the Fillmore Auditorium, December 10. First performance as the Grateful Dead for which there is actually proof in the form of an undated poster: the Acid Test in Muir Beach, December 11 or 18.

This photo of the Grateful Dead taken by Bob Seidemann became a head-shop poster in 1967.

At the beginning of the Acid Test era, which would continue into the fall of 1966, the Grateful Dead were closely aligned with Kesey and the Pranksters. By the time of the planned-but-cancelled Acid Test Graduation on October 31, 1966, though, the two communities had drifted apart.

According to Meriwether, it really wasn’t because Kesey’s extramarital girlfriend, Mountain Girl, had moved in with Garcia by then. “Even if there was friction,” Meriwether says, “the band always treated Kesey as a fellow traveler. They played a benefit for Kesey in August of 1972, and by the 1980s and ’90s, when Jerry was recuperating from illnesses, he would go up to Oregon and spend time on Kesey’s farm.

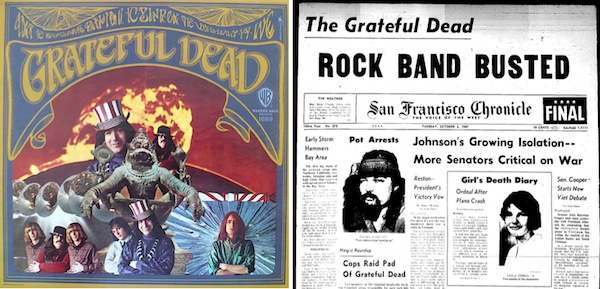

The Grateful Dead’s first album was released in March of 1967. That October, band members Pigpen and Bob Weir were busted for possession of marijuana. Originally charged with felonies, the rock stars got off with wrist slaps—misdemeanors and light fines.

“No,” Meriwether continues, “I think it was much simpler than that. By early 1966, I think the band had figured out that the negative publicity surrounding LSD and drugs in general was something that had the capacity to be enormously damaging. They wanted a recording contract, and you didn’t get a recording contract with a major label in those days if you were a flamingly drugged-out band. They had tremendous street smarts,” he says.

In keeping with those street smarts, they eventually got their record deal and released their first album in the spring of 1967, before getting famously busted for marijuana possession that fall. More important, though, than their sense of PR and the good fortune of the bust’s timing, they knew better than to call themselves Mythical Ethical Icicle Tricycle or Vanilla Plumbago.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.