Trainspotting boomed and peaked in the post-war years. But even when tens of thousands of boys – and it was mostly boys – were spending their free time spotting trains, it remained an awkward hobby, an activity on the social fringes derided and sneered at by the knowing. That lack of acceptance should make trainspotting cool. Maybe it it.

The National Rail Museum (NRM) notes:

By the 1950s, trainspotting was extremely popular and many unaccompanied youngsters could be found at stations. Some authority figures wanted to ban the hobby as they were concerned about the potential for juvenile delinquency. When Willesden Junction closed to spotters in June 1954, it was suggested that this potentially affected up to half a million spotters.

According to the NRM “the first person to keep records of locomotive numbers and names in a separate journal was 14 year old Fanny Johnson in 1861. Her lists are mentioned in a Great Western Railway (GWR) magazine article published in 1935.”

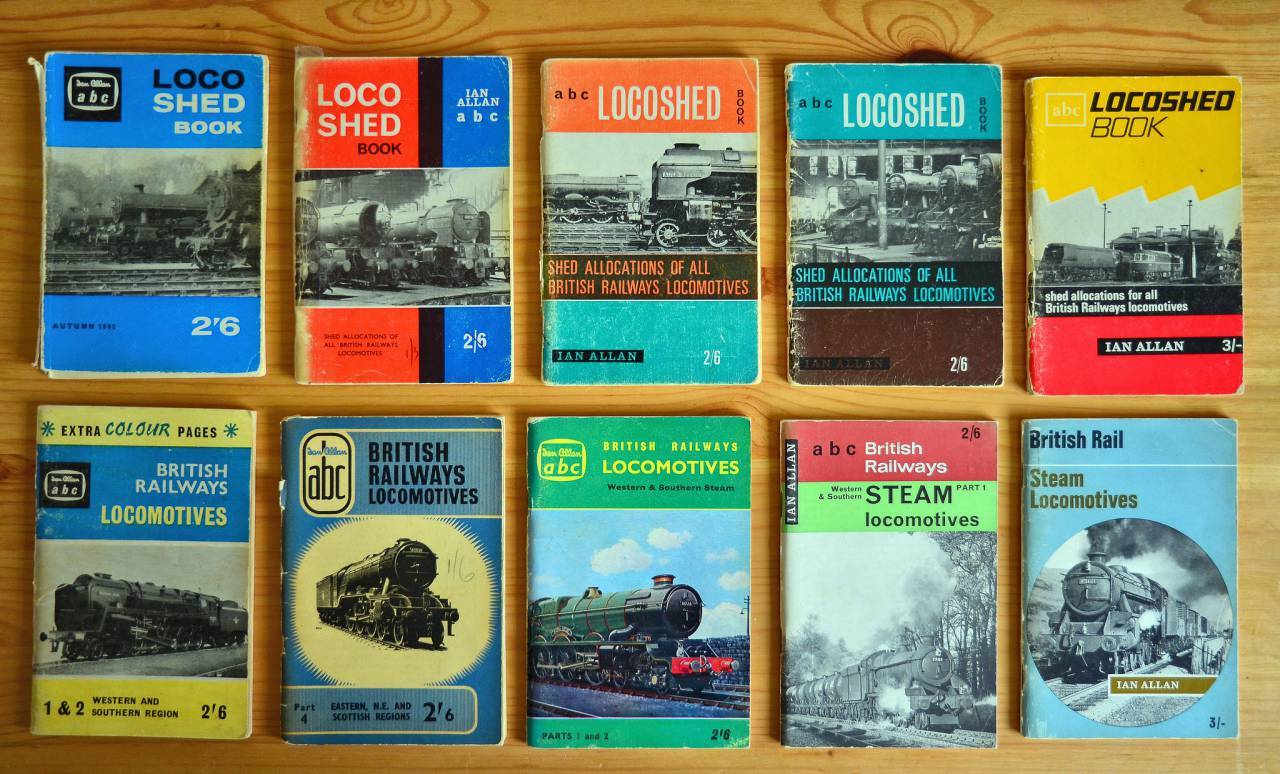

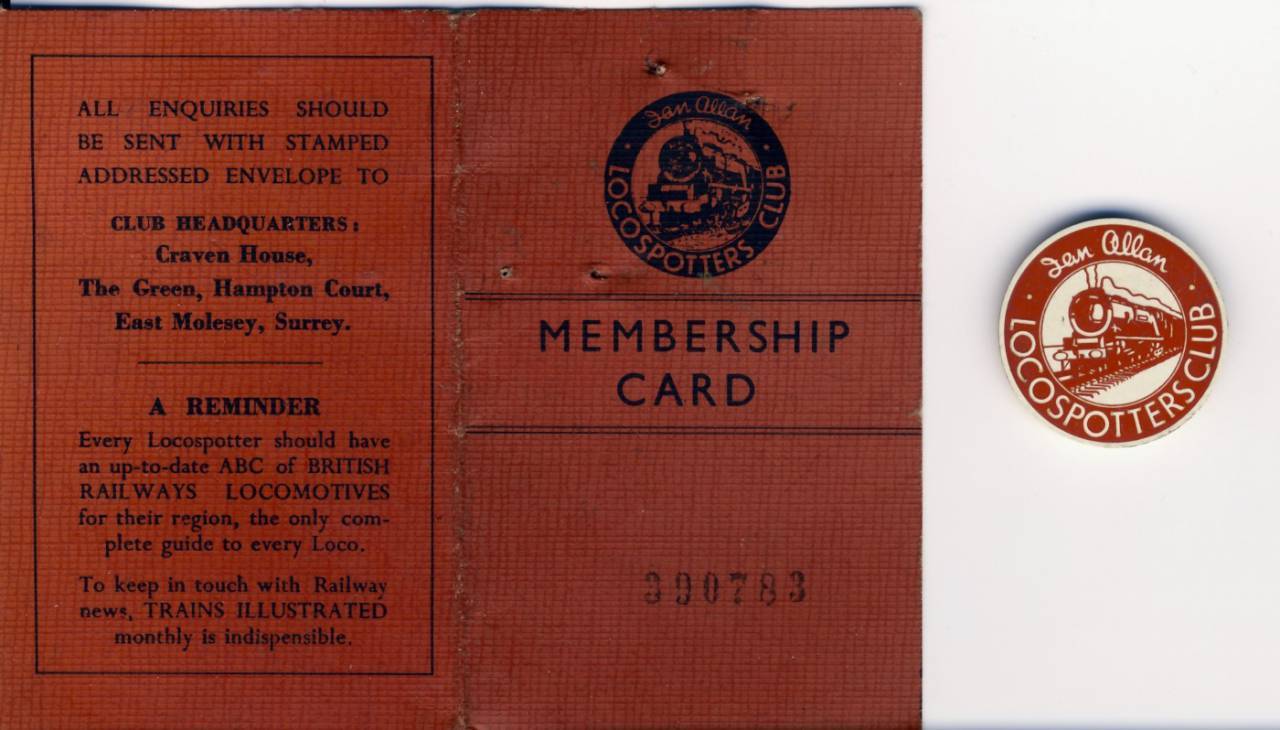

But the catalyst for the trainspotting fad was Ian Allan, who in 1942 published the first ABC spotter book and in 1948 created The Ian Allan Locospotters’ Club.

May 1933: Trainspotting schoolboys watching an LMS train pass by at Tring. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

In 1993, Ian Allan considered his work. The premable gave us a history of his work:

Trainspotting began in 1942 when Mr Allan was a 19-year-old trainee in the public-relations office of the Southern Railway at Waterloo. Tired of replying to letters from railway enthusiasts demanding details of locomotives, he suggested that the office produce a simple booklet listing their vital statistics. His boss was not interested, so Mr Allan decided to do it himself.

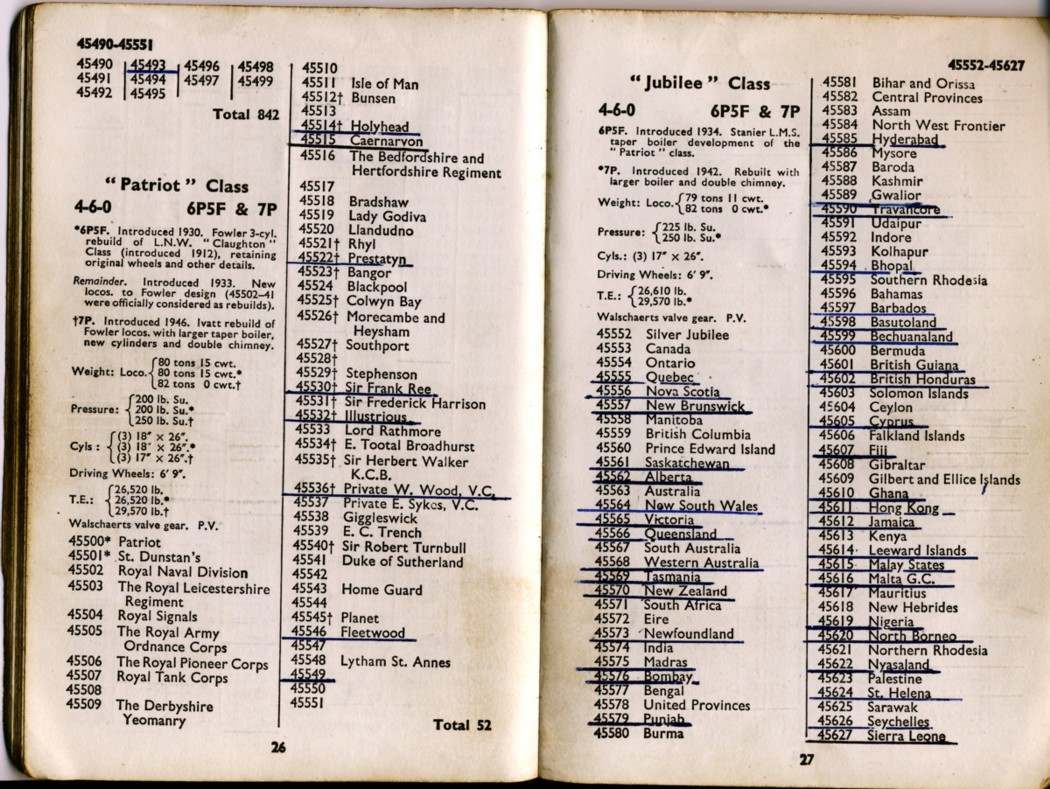

The ABC of Southern Locomotives was a simple pocket- sized index of engine numbers and types. At a shilling each, 2,000 copies sold out immediately. ABC guides to other railway companies soon followed.

Locospotting – Mr Allan’s preferred phrase – was identified as a phenomenon in 1944, when a group of adolescent boys were arrested on the tracks at Tamworth, the nearest station on the west coast main line to Birmingham. Partly in order to teach safety to young spotters, Mr Allan started the Loco- spotters Club.

By the late Forties it had a quarter of a million members. In the Fifties and Sixties a million ABC guides, listing 20,000 locomotives, were being sold every year. The police had to be called in on holidays to keep spotters in order at such key stations as Willesden, Clapham Junction and Tamworth.

Allan mused on why people mock and even hate trainspotters?

“I suppose people just dislike people who are different… it seems to be because they wear berets and haversacks and dirty mackintoshes and cover them with badges… The bulk of them are perfectly normal people, chartered accountants, engineers. It goes right down the scale to a few who are decidedly odd… I usually go incognito to railway meetings. If I meet them and they want to discuss the relative merits of one class of loco or the other – I just say ‘Can’t we talk about something else?'”

At which poiont we turn to experts in science, who come up with the cheerless diagnosis that trainspotters are most likely mentally defective:

Dr Uta Frith of the Medical Research Council’s Cognitive Development Unit, has said that trainspotters and other obsessive collectors of trivia, may be suffering from Asperger’s Syndrome, a mild form of autism.

The syndrome, identified by a Viennese doctor shortly after the Second World War, is characterised by social ineptness, an over-literal and pedantic approach to language, a lack of sense of irony or humour and obsessively pursued hobbies – finding, as it were, safety in numbers.

You see. Trainspotters are ‘lacking’. They do not have more; they have less.

Charming.

circa 1935: A group of boys relax in the sun near a railway track. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

The National Rail Museum has collected come of the trainspotters’ stories:

Richard Smith:

One day, as I was standing at one of my regular spots, I noted the approach of a light engine. The fireman was gesticulating at me to change some hand points, which I duly did with some difficulty. As the loco pulled alongside, the crew indicated that I should get aboard. We went round the angles and finally parked up alongside the north side of the shed under the water tank. The crew then departed and asked me to “look after” the loco for them. After a short while I realised they were having me on and I beat a hasty retreat before the shed foreman put in an appearance.

Via David Ward

Roy Lawrence

The inspiration for my gang’s name, The Red Hand Gang, was obvious. Whenever I returned home after a days climbing all over the ranks of condemned locomotives, my palms were always covered in rust.

Any visit to Barry scrap-yard meant trying to get along the rows of engines without ever touching the ground. Why I can’t remember, unless this qualified as cabbing everything in the yard. Rusting handrails, warmed by the sun, allowed you to swing along the sides of engines for hours, stopping only for lunch and some sausage sandwiches, covered with red fingerprints. This ensured our age group never had any iron deficiencies.

Bunking sheds came with varied success. Aston shed was notorious for getting caught and being ejected from. Even ducking down under the booking-in window and making a dash for the lines of Brits and Scots usually ended in tears. That was until my Mum offered to take me there one Saturday when she persuaded the shed master to let me have a guided tour. I was famous at school and everyone wanted a Mum like mine.

Railfans on a 1939 camera excursion train. This photo may have been taken in Thurston, Ohio where there was a Y.

Glyn Sunman

No one had seen Kingfisher. Even the older lads who’d been at it for years didn’t have Kingfisher. South Africa and India – yes. But not Kingfisher… So imagine my excitement when, on arriving at school one morning, Charlie and John came charging up – “Kingfisher’s in”…

And so it was, after an interminable day in school, I found myself galloping off, past the sheds to the yards beyond, where, with any luck, my quarry lay…

“Did you get it?” I was asked the next day.

“Yep” I said as casually as I could.

“Liar!”

“I did – it was just there where you said”

“Well you’re lying – it went out yesterday lunch-time”

“It can’t have done – I saw it”

“It did – Wreggie’s dad’s a driver – an’ ‘e said it went out at lunch-time”

“Well that’s odd ‘cos I saw it” I insisted, rather unconvincingly.Well lying is one thing but dishonesty is another. I never did underline it in my Ian Allan spotter’s book. That would be sacrilege.

Spotter: Keypublishing

The Fifties was a decade in which parents imposed strict control over children, subscribing to uniformity, not individuality, but as train spotting involved the discipline of collecting numbers the vast majority of grown-ups unanimously accepted the hobby as being some sort of educational tool. Indeed, the hobby appealed to all ages during the Fifties. For example, a major milestone took place on April 20th 1958 when the BBC screened the first ‘Railway Roundabout’ by John Adams and Patrick Whitehouse. The programme was aimed at children, but rumour has it that thousands of adults secretly dashed home from work to catch the BBC’s children’s hour…

As for train spotter’s fashions? By the very nature of the hobby, boys donned sensible pullovers, knee- length short trousers, or thick denim jeans with turn-ups (turned down as legs grew longer) and duffel coats fastened by wooden pegs instead of buttons and, dare I say it – anoraks – ouch! Of course, boys still liked to play games of fifteen-a-side soccer and a marathon round of hop-scotch in the street, but as soon as we developed an irresistible urge to swap and collect – birds eggs, used stamps, old coins, and cigarette cards – then it was only natural that engine numbers figured high on our list of priorities. Even better, it didn’t require a huge financial commitment, which made all the difference in the post-war Fifties. It probably explains why hard-up parents gave the hobby a universal thumbs-up.

January 05, 1953: A group of young trainspotters on board a special train at London Bridge Station, London, 5th January 1953. The ‘Spotters’ Special’ is taking four hundred young rail enthusiasts on a trip to the locomotive works and engine sheds at Stratford in East London. The trip has been organized by the Ian Allen Loco Spotters’ Club, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary and the enrolment of its one hundred-thousandth member. (Photo by Harry Todd/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

1953. Trainspotters Ian Herbert, Michael Harris and Michael McDonough on board a special train at London Bridge Station, London, 5th January 1953. The ‘Spotters’ Special’ is taking four hundred young rail enthusiasts on a trip to the locomotive works and engine sheds at Stratford in east London. The trip has been organized by the Ian Allen Loco Spotters’ Club, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary and the enrolment of its one hundred-thousandth member. (Photo by Ron Burton/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

3rd August 1960: Ten year old trainspotter John Speed of Fareham, Hampshire, examining a Battle of Britain Class locomotive at the Southern Region British Railways Works at Eastleigh. (Photo by William Vanderson/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

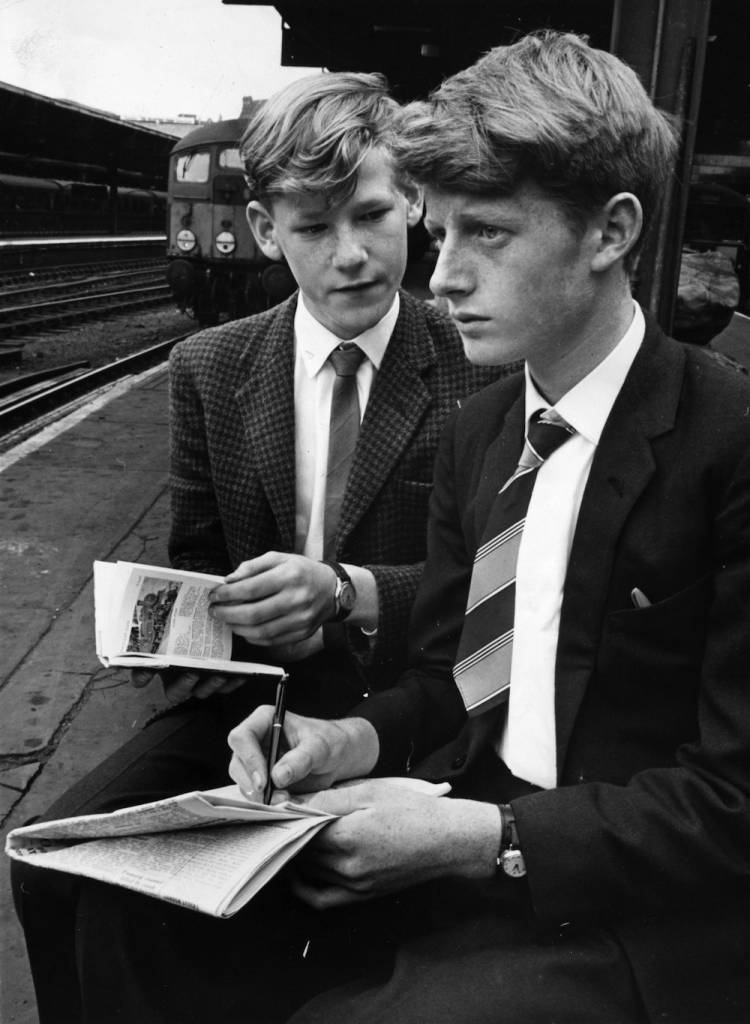

24th August 1963: Teenage trainspotters Peter James and Paul Sliwinski who witnessed a rail crash while trainspotting. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

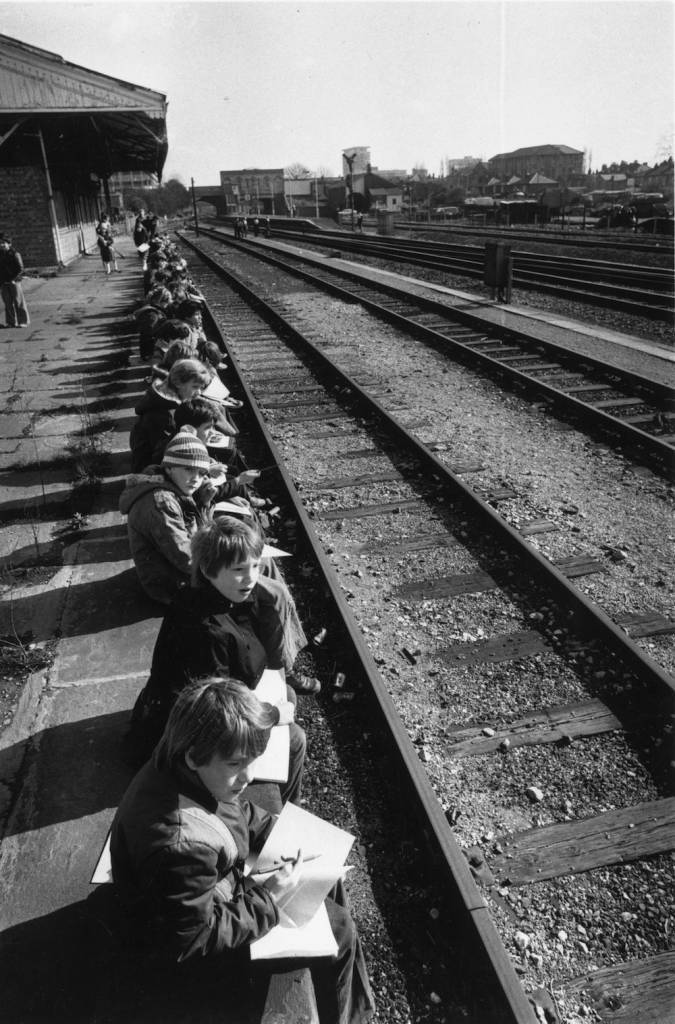

1979: School children sit along the edge of the platform at West Ealing station, London. (Photo by John Minihan/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.