“The more he learns from experience the more truly he can imagine”

– Ernst Hemingway on writing, 1935

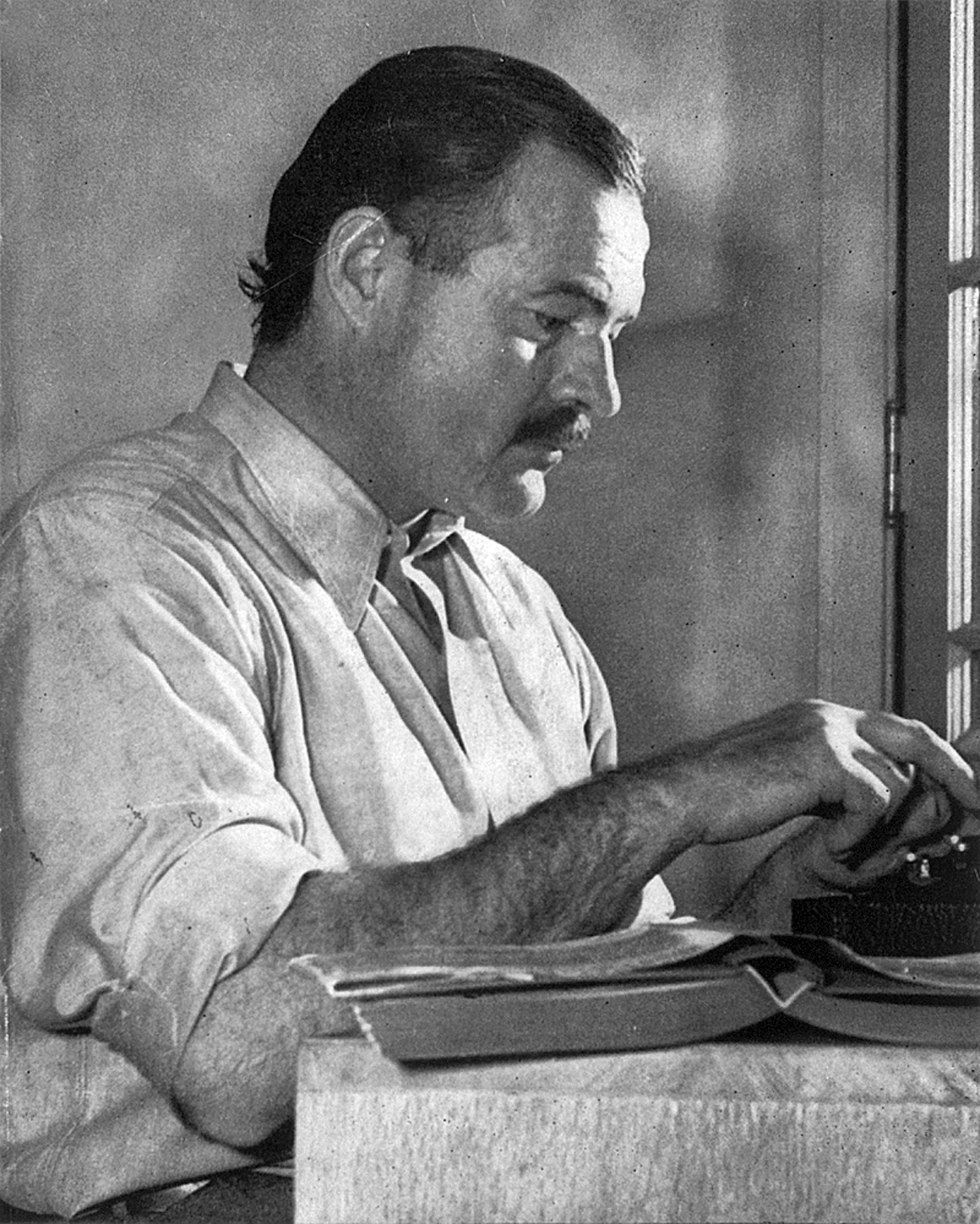

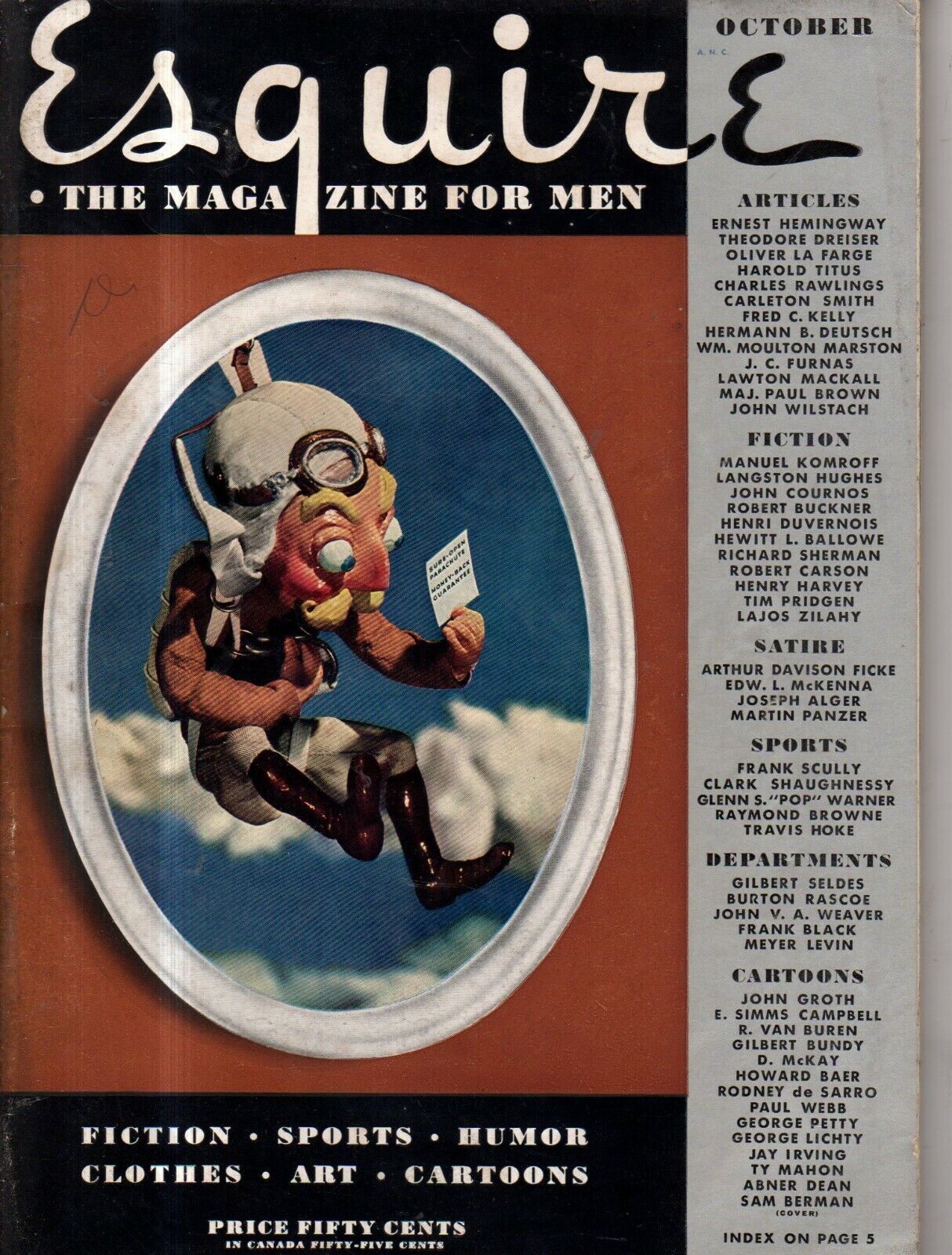

In his October 1935 column for Esquire magazine called Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter, Ernest Hemingway (July 21, 1899–July 2, 1961) shared his tips for writing with an aspiring author nicknamed ‘Mice’ (abbreviated from Maestro – on account of his ability to play the violin). In the guise of ‘Y.C’ (Your Corespondent), Hemingway addresses a young man who had in real life hitch-hiked from upper Minnesota to the writer’s home in Key West, Florida, to ask him a few questions about writing.

Hemingway explained why he was doing it:

If they can deter anyone from writing he should be deterred. If they can be of use to anyone your correspondent is pleased. If they bore you there are plenty of pictures in the magazine that you may turn to. Your correspondentʼs excuse for presenting them is that some of the information contained would have been worth fifty cents to him when he was twenty-one.

Writing as both himself and as Mice, Hemingway was living his own advice to “get in somebody else’s head for a change”. And not to take it too personally – “If I bawl you out try to figure what I’m thinking about as well as how you feel about it.”

And you get there by listening. “When people talk listen completely,” Hemingway advises. “Donʼt be thinking what youʼre

going to say. Most people never listen. Nor do they observe.” And read a lot – this column also included his 16 books every writer should read.

Mice: What do you mean by good writing as opposed to bad writing?

Your correspondent: Good writing is true writing. If a man is making a story up it will be true in proportion to the amount of knowledge of life that he has and how conscientious he is; so that when he makes something up it is as it would truly be. If he doesnʼt know how many people work in their minds and actions his luck may save him for a while, or he may write fantasy. But if he continues to write about what he does not know about he will find himself faking. After he fakes a few times he cannot write honestly any more.

Mice: Then what about imagination?

Y.C.: Nobody knows a damned thing about it except that it is what we get for nothing. It may be a racial experience*. I think that is quite possible. It is the one thing beside honesty that a good writer must have. The more he learns from experience the more truly he can imagine. If he gets so he can imagine truly enough people will think that the things he relates all really happened and that he is just reporting.

The conversation continues, with Mice asking how writing differs from reporting (answer: with writing you get the complete story that stands the the of time and place) – a reply he does not fully understand. He wants to how you get the first word down.

Mice (undeterred): Tell me some more about the mechanics of writing.

Y.C.: What do you mean? Like pencil or typewriter? For chrissake.

Mice: Yes.

Y.C.: Listen. When you start to write you get all the kick and the reader gets none. So you might as well use a typewriter because it is that much easier and you enjoy it that much more. After you learn to write your whole object is to convey everything, every sensation, sight, feeling, place and emotion to the reader. To do this you have to work over what you write. If you write with a pencil you get three different sights at it to see if the reader is getting what you wanted him to. First when you read it over; then when it is typed you get another chance to improve it, and again in the proof. Writing it first in pencil gives you one-third more chance to improve it. That is .333 which is a damned good average for a hitter. It also keeps it fluid longer so that you can better it easier.

And then to give yourself the best chance of actually finishing the book: “The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next… and never be stuck”; and “read it all every day from the start, correcting as you go along, then go on from where you stopped the day before.”

More advice from Hemingway in how to write a six-word short story; how to camp well; how to eat raw lion; what to read in isolation; how to get cats to love you; and the importance of keeping a notebook.

Via: Diane Drake

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.